Once, the lyric essay did not have a name.

Or, it was called by many names. More a quality of writing than a category, the form lived for centuries in the private zuihitsu journals of Japanese court ladies, the melodic folktales told by marketplace troubadours, and the subversive prose poems penned by the European romantics.

*

Before I came to lyric essays, I came to writing. When my teacher asked the class to write a story for homework, I couldn’t believe my luck. But in response to my first attempt, she wrote in the margins: this is cliché.

As a first-generation college student, I was afraid I didn’t know how to tell a story properly, that my mind didn’t work that way. That I didn’t belong in a college classroom, wasn’t a real writer.

And yet, language pulled me. Alone in my dorm room, I arranged and rearranged words, whispered them aloud until the cadences pleased me, their smooth sounds like prayers. I had no name for what I was writing then, but it felt like a style I could call my own.

–Erica

*

While the origins of the lyric essay predate its naming, the most well-known attempt to categorize the form came in 1997, when writers John D’Agata and Deborah Tall, coeditors of Seneca Review, noticed a “new” genre in the submission queue—not quite poetry, but neither quite narrative.

This form-between-forms seemed to ignore the conventions of prose writing—such as a linear chronology, narrative, and plot—in favor of embracing more liminal styles, moving by association rather than story, dancing around unspoken truths, devolving into a swirling series of digressions.

I had no name for what I was writing then, but it felt like a style I could call my own.D’Agata and Tall’s proposed term for this kind of writing, “the lyric essay,” stuck, and in the ensuing decade the word would be adopted by many essayists to describe the kind of writing they do.

*

As a genderfluid writer and as a writing teacher, I’ve always appreciated the lyric essay as a literary beacon amid turbulent narrative waves. A means to cast light on negative space, to illuminate subjects that defy the conventions of traditional essay writing.

Introducing this writing style to students is among my favorite course units. Semester after semester, the students most drawn to the lyric essay tend to be those who enter the classroom from the margins, whose perspectives are least likely to be included on course reading lists.

–Zoë

*

Since its naming, the lyric essay has existed in an almost paradoxical space, at once celebrated for its unique characteristics while also relegated to the margins of creative nonfiction. Perhaps because of this contradiction, much of the conversation about the lyric essay—the definition of what it is and does, where it fits on the spectrum of nonfiction and poetry, whether it has a place in literary journals and in the creative writing classroom—remains unsettled, extending into the present.

I thought getting accepted into a graduate program meant I had finally opened the gilded, solid oak doors of academia—a place no one in my family, not a parent, an aunt or uncle, a sibling or cousin, had ever seen the other side of.

But at my cohort’s first meeting in a state a thousand miles from home, I understood I was still on the outside of something.

“Are you sure you write lyric essays?” the other writers asked. “What does that even mean?”

–Erica

*

The acceptance of the lyric form seems to depend largely on who is writing it. The essays that tend to thrive in dominant-culture spaces like academia and publishing are often written by writers who already occupy those spaces. This may be part of why, despite its expansive nature, many of the most widely-anthologized, widely-read, and widely-taught lyric essays represent a narrow range of perspectives: most often, those of the center.

To name the lyric essay—to name anything—is to construct rules about what an essay called “lyric” should look like on the page, should examine in its prose, even who it should be written by. But this categorization has its uses, too.

Much like when a person openly identifies as queer, identifying an essayistic style as “lyric” provides a blueprint for others on the margins to name their experiences—a form through which to speak their truths.

–Zoë

*

The center is, by definition, a limited perspective, capable of viewing only itself.

In “Marginality as a Site of Resistance,” bell hooks positions the margins not as a state “one wishes to lose, to give up, or surrender as part of moving into the center, but rather as a site one stays on, clings to even, because it nourishes one’s capacity to resist.”

To write from the margins is to write from the perspective of the whole—to see the world from both the margins and the center.

*

I graduated with a manuscript of lyric essays, one that coalesced into my first book. That book went on to win a prize judged by John D’Agata and named for Deborah Tall. I had finally found my footing, unlocked that proverbial door. But skepticism followed me in.

On my book tour, I was invited to read at my alma mater alongside another writer whose nonfiction tackled pressing social issues with urgency, empathy, and wit. I read an essay about home and friendship, about being young and the hard lessons of growing up.

After the reading, we fielded a Q&A. The Dean of my former college raised his hand.

“I can see what work the other writer is doing quite clearly,” he said to me. “But what exactly is the point of yours?”

–Erica

*

Writing is never a neutral act. Although a rallying slogan from a different era and cause, the maxim “the personal is political” still applies to the important work writers do when they speak truth to power, call attention to injustice, and advocate for social change.

Because the lyric essay is fluid, able to occupy both marginal and center spaces, it is a form uniquely suited to telling stories on the writer’s terms, without losing sight of where the writer comes from, and the audiences they are writing toward.

When we tell the stories of our lives—especially when those stories challenge assumptions about who we are—it is an act of resistance.

*

Many of the contemporary LGBTQIA+ essayists I teach in my classes write lyrical prose to capture queer experience on the page. Their works reckon with nonbinary family building and parenthood, the ghosts of trans Midwestern origin, coming of age in a queer Black body, the over- whelming epidemic of transmisogyny and gendered violence.

To write from the margins is to write from the perspective of the whole.The lyric essay is an ideal container for these stories, each a unique prism reflecting the ambiguous, messy, and ever-evolving processes through which we as queer people come to understand ourselves.

–Zoë

*

Lyric essays rarely stop to provide directions, instead mapping the reader on a journey into the writer’s world, toward an unknown end. Along the way, the reader learns to interpret the signs, begins to understand that the road blocks and potholes and detours—those gaps, the words left unspoken on the page—are as important as the essay’s destination.

*

The lyric essays that have taught me the most as a writer never showed their full hand. Each became its own puzzle, with secrets to unlock. When the text on a page was obscured, the essay taught me to fill in the blanks. When the conflict didn’t resolve, I realized irresolution might be its truest end. When the segments of the essay seemed unconnected, I learned to read between the lines.

The most powerful lyric essays reclaim silence from the silencers, becoming a space of agency for writers whose experiences are routinely questioned, flattened, or appropriated.

Readers from the margins, those who have themselves been silenced, recognize the game.

–Erica

*

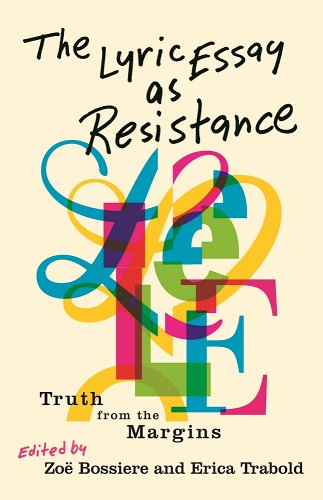

The twenty contemporary lyric essays in this volume embody resistance through content, style, design, and form, representing of a broad spectrum of experiences that illustrate how identities can intersect, conflict, and even resist one another. Together, they provide a dynamic example of the lyric essay’s range of expression while showcasing some of the most visionary contemporary essayists writing in the form today.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Lyric Essay as Resistance: Truth from the Margins, edited by Zoë Bossiere and Erica Trabold. Copyright © 2023. Available from Wayne State University Press.