Language—no matter how we handle it, try to control it, or share it—is powerful. In recent years, memes have emerged as a fragmented written and symbolic dialect of the internet; they have also become calls to action. In Meme Wars, three researchers analyze how the spread of trollish phrases and iconography online led to the real-world attack on the Capitol on January 6, 2021. Those communications built up complex conspiracies, such as the idea that the election was stolen. In short, they created a story.

Human beings all have this impulse to develop narratives, but that “storification,” as Peter Brooks describes it, can flatten our understanding of the world and one another. The information we consume nonstop online, in the news, and during conversation requires an analytical eye. Teaching that skill to the next generation may start in the classroom. Still, as Katherine Marsh warns, learning to parse the meaning of text shouldn’t come at the expense of coming to love literature. There must be some middle ground where we can both play with language and understand its power.

Authors, who have a heightened awareness of the force of words, frequently manipulate them to unsettle their audiences. Some do so with unconventional diction and twisted sentences; others make it the premise of their novels. In Han Kang’s new novel Greek Lessons, two characters must discover ways to communicate as one loses his sight and the other one goes mute. Language itself becomes a character, Sarah Chihaya argues in her review, that both gives and takes from Kang’s protagonists over the course of the novel. Other authors challenge norms by rejecting colonially imposed languages. More than a decade into his career, the author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o started to write in his mother tongue, Gĩkũyũ, instead of English. He translates his own work, but his titles are released in English two years after the initial publication in order to prioritize the first edition. He’s acknowledging that small choices in diction or idiom can have stark consequences.

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Getty; The Atlantic

How memes led to an insurrection

“But social media did not create culture wars. Instead, we’ve found, social media did to culture wars what spinach did to Popeye—it juiced them up. Suddenly you didn’t need a radio show to get your idea to millions of people. You just needed a viral tweet, or to figure out the desires of a Facebook algorithm programmed to boost outrageous and emotionally stirring content. With the scale and ease of social media, culture warriors from across the country and globe were able to find one another and gather in communal spaces where their ideas could grow.”

📚 Meme Wars, by Joan Donovan, Emily Dreyfuss, and Brian Friedberg

Ben Hickey

Beware the ‘storification’ of the internet

“We’re telling ourselves stories in order to live, yes, but we’re also turning ourselves into stories in order to live.”

📚 Seduced by Story, by Peter Brooks

Hulton Archive / Getty

Why kids aren’t falling in love with reading

“Close reading may be easy to measure, but it’s not the way to get kids to fall in love with storytelling. Teachers need to be given the freedom to teach in developmentally appropriate ways, using books they know will excite and challenge kids.”

📚 The Witch of Blackbird Pond, by Elizabeth George Speare

📚 Amelia Bedelia, by Peggy Parish

📚 To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

📚 The Giver, by Lois Lowry

📚 Diary of a Wimpy Kid, by Jeff Kinney

Illustration by The Atlantic. Sources: Ferdinando Scianna / Magnum; Millennium Images.

A novel in which language hits its limit—and keeps on going

“Language, like some powerful alien intelligence or a god, must be appeased in order to be reclaimed—and perhaps this can be achieved only by a submission to vulnerability, to those emotions that are too frightening and deeply embedded to say aloud or commit to paper.”

📚 Human Acts, by Han Kang

📚 The White Book, by Han Kang

📚 The Vegetarian, by Han Kang

📚 Greek Lessons, by Han Kang

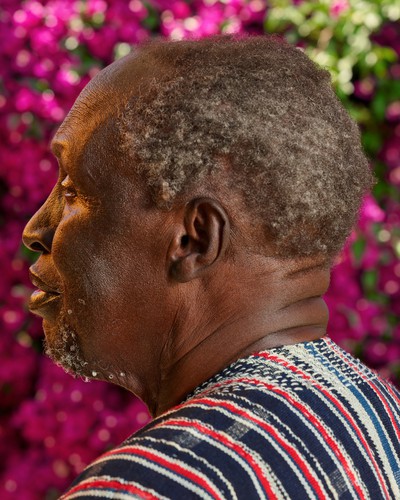

Awol Erizku for The Atlantic

“The problem with language is hierarchy. It must have come with the conception of the modern state: ‘One language, one language!’ But it is hierarchy. It’s the oppression of many languages in favor of the one. In order for one language to be, others must die. It’s so backward and unproductive.”

📚 The Perfect Nine, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

📚 Decolonising the Mind, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

📚 Devil on the Cross, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

📚 Dreams in a Time of War, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

📚 Birth of a Dream Weaver, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Elise Hannum. The book she’s current reading is Romantic Comedy, by Curtis Sittenfeld.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.