That summer, Porto Marina Way was still a new road. Construction crews had cut switchbacks into the coastal slope a few years before, and now the motorway snaked around the Italianate mansions down the hillside to Harrison Post’s house at the edge of the ocean. From there, he could watch the waves crash against the shore.

Three miles out, America stopped. That’s where the gambling boats dropped anchor. At night their lights glittered in the dark Pacific. It was 1929, and the shadow world existed in plain sight.

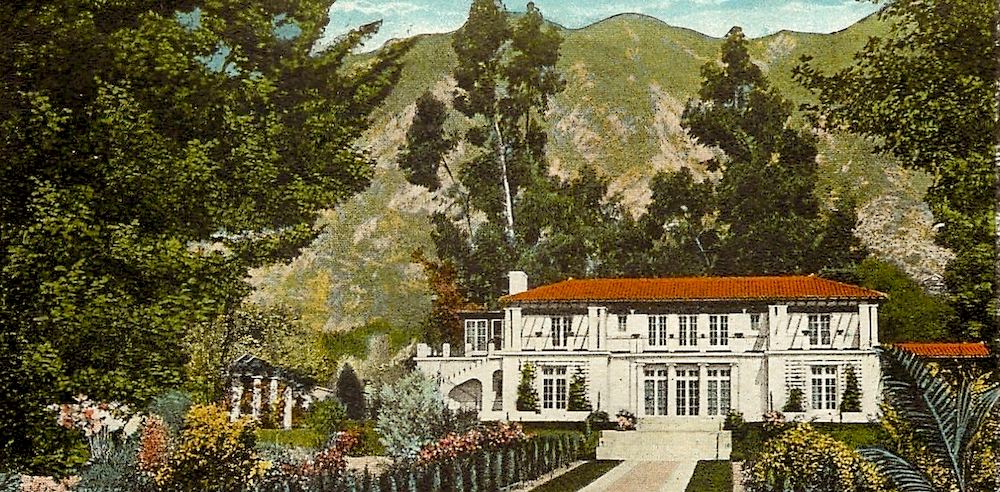

The twisting streets and terraced developments of Castellammare, the latest luxury subdivision in Los Angeles’s Pacific Palisades, had been modeled after the Amalfi Coast, and the new residents—film directors, movie stars, a wool magnate—were required to build their houses in a suitably Mediterranean style. Harrison Post complied. He filled his seaside home with ornate tapestries and dark, heavy furniture and called it Villa dei Sogni—House of Dreams.

A small, dark-haired man, he had elegant hands that were usually engaged with a cigarette. He owned a set of dominoes made of ivory and gold and when he played he always won—one tile clicking against another, mind and fingers in harmony until he slid the last ivory in place and smiled: “Domino.” Then on to the next cigarette.

He was not a movie star or an industry tycoon, though he counted those people among his friends. He was fine-boned and he had dark, deep-set eyes. His gaze was watchful and appraising. He longed for his surroundings to be beautiful yet objected to charges of snobbery. “It is not so,” he once wrote when so accused, though he did concede, “I do dislike vulgarians.” It was a subtle distinction, and he was a man who cherished subtlety.

True, the Rolls-Royce wasn’t subtle. It was one of five that had been manufactured that year. He’d had it specially painted with yellow pinstripes.

“I do evade many things,” he once wrote. He had good reason to evade.The average person in America probably knew of Harrison’s good friend Bebe Daniels. All they had to do was pick up Photoplay or any other fan magazine to learn about the starlet’s arrest for speeding, her extravagant wedding to leading man Ben Lyon, or her day playing ping-pong with Charlie Chaplin. But the average person wouldn’t know Harrison Post.

When his name did end up in the papers, he was usually identified as a “clubman” or an “art collector,” words that meant wealth. Some labels were more blunt: “Hollywood millionaire.” There were other words that people used for him, but those were whispered, or written in unsigned letters sealed inside envelopes with no return address.

“I do evade many things,” he once wrote. He had good reason to evade and good reason not to say what it was that he evaded.

On Sundays, Harrison took his Rolls-Royce to the polo field at the Riviera Country Club and watched the horses thunder across the green turf as their riders lunged low, mallets swinging. It was called the sport of kings, but here it belonged to LA’s version of royalty, movie stars like Spencer Tracy and Will Rogers. In the stands, Clark Gable peered through binoculars. Beyond the grass lay a spread of orchards, and, farther still, the high ridge of the Santa Monica Mountains sheltered them all.

Harrison wasn’t merely a man who knew famous people. He was a man who famous people knew. They knew him to be a lavish host, opening his homes—he had another closer to the heart of LA in West Adams—for a production of Macbeth or a luncheon for riders from the club. That summer he welcomed Robert Ehrmann, the tennis ace from Cincinnati, to Porto Marina Way.

The young man had come west with his parents a few months earlier to hone his game at the Miramar Beach Club. By June, Robert’s parents had left, while he, seduced by the company and the sunshine, remained. Tall with brown hair, the tennis player made friends easily on the club circuit. Champion May Sutton Bundy, who years before had shocked British spectators by baring her elbows and ankles on court, had invited Robert to join her at Wimbledon that season, but England’s grass courts had none of the allure of the Villa dei Sogni.

Harrison lived there with his sister, the Countess Barbieri. A small woman, about five foot four, she had the same deep-set eyes as her brother, though hers were pale blue. She was passionate about her Brussels griffon, Sidlaw Trotsky, and happy for an audience. Together she and Harrison shared their history with Robert, who in turn shared it with a hometown reporter. The tale published in a Cincinnati paper was a sad one but thrilling too. It went like this:

The two siblings had grown up in Montana. Their father, an early pioneer of the state, made his “vast fortune” in copper and silver. They were young when their mother died. Soon after, Mr. Post died too, and they became orphans—though, as it turned out, the fortunate kind.

Their late father had been good friends with another Montana pioneer, Senator William Andrews Clark Sr., and while they didn’t say it in these words, everyone knew Clark was a man of phenomenal wealth, far beyond their father. Along with sprawling mines of copper, zinc, and silver, Clark owned streetcars, postal services, banks, forests, water rights, and newspapers. He’d spent $20 million to build a railroad from San Pedro, California, to Salt Lake City. People called it the Clark Road. A sleepy depot along the route would one day become Las Vegas. Clarkdale, Arizona. Clark County, Nevada. He made his fortune in the Gilded Age and left his mark well into the 20th century.

To the general public, the man who had accumulated and presided over this immense fortune was a peculiar figure—short, dandified, birdlike with small bright eyes, a bristly goatee, and a whorl of white hair that he sculpted into theatrical tufts. He was considered prickly and aloof; “there are icicles in his handshake,” wrote historian C. B. Glasscock.

But that wasn’t how he’d appeared to the Post siblings. As they explained, the senator had adopted the two children and raised them as his own, sending his young wards abroad to be educated, where, the newspaper reporter observed, they were “brought into close contact with that polished mondanity [sic] which is the acme of the gifted ages handed down to succeeding generations from time immemorial.”

The senator had been dead four years when Robert Ehrmann arrived at Villa dei Sogni, but the late tycoon’s legacy was there in the “handsome house filled with treasures acquired from many palaces in Italy.” Harrison had also amassed an impressive library, full of “rare books and countless first editions” that the columnist likened to a miniature Huntington Library, the sprawling property established by railroad magnate Henry Huntington. And yet the more astute observer of LA’s high society would have drawn a comparison to the holdings of a different nobleman: the Clark Library.

Harrison’s book collection was small compared to the one that belonged to the senator’s son, William Andrews Clark Jr. Will—as Harrison called him—had a library of ten thousand rare books on his estate in West Adams, which he had deeded a few years earlier along with the building, a beaux arts curio of brick and marble, to the University of California.

The column doesn’t say much about Will, but it needn’t have. Most readers would’ve known his name was synonymous with unimaginable wealth. Smooth-faced, unlike his father, Will kept his chestnut hair neatly parted and combed to one side. Also unlike his father, he wasn’t known for accumulating money, but for giving it away. In 1919, Will had spent $200,000 to found the Los Angeles Philharmonic and since then had spent even more to keep it afloat. He was also one of the major donors behind the creation of the Hollywood Bowl and helped underwrite the orchestra’s concerts in the amphitheater. Along with the library, he built an observatory on his palatial grounds, where he sponsored lectures and welcomed visitors to gaze at the night sky through his telescopes.

Will was twenty years older than Harrison, but the two men were clearly close. Robert Ehrmann reported to the Cincinnati journalist that Will had invited Harrison, his sister, and Robert to his vacation home—“a veritable palace”—in Montana for the summer. He also mentioned that Will and Harrison were planning to buy the Palais Rose in Paris. The opulent mansion on Avenue Foch belonged to Anna Gould, the socialite daughter of robber baron Jay Gould. The building, modeled after the Grand Trianon of Versailles, would pass from one American heir to another.

Robert Ehrmann came from a well-to-do family and moved in moneyed circles, but that still hadn’t prepared him for the brother and sister who lived by the sea among antiques and jewels, who glided between America and Europe as if boarding a streetcar, if a streetcar came with champagne, servants, and an endless supply of cigarettes. The tennis ace was plainly enthralled by the siblings’ rarefied world and the article concluded with the reporter musing that the young man might be well fitted, as Harrison Post clearly was, to the “life of the dilettante.”

And yet there were others who weren’t so readily beguiled, and there were other details about Harrison Post that didn’t make it into the Cincinnati Enquirer’s account. If the story that he and his sister spun for Robert Ehrmann seemed too charmed to be true, that’s because it was. Countess Barbieri was not a countess. Her name was Gladys, and her ex-husband, whose name she still used, wasn’t a European nobleman. He was from Chicago. Their father, Mr. Post, hadn’t been a mining magnate. He hadn’t even been Mr. Post. His name was Mark Harrison. He’d lived in many states in America, but Montana hadn’t been one of them. Who, then, was Harrison Post?

There were those who thought they knew. They found him suspiciously dark, suspiciously effete, suspiciously Jewish, or, in the words of one detractor, “with Semitic cast.” There were other words that trailed the man with the Rolls-Royce and the famous friends and the villa on the coast: “vice,” “perverted practices,” “unnatural relations,” “degenerate.” Few believed that he was a foster brother to Will Clark or that the two men were even friends—not exactly. Their relationship was far more intimate than that, and in 1929 it was criminal.

So much was criminal then. Just down the way from Villa dei Sogni was Doc Law’s Drugstore. Everyone knew the pharmacy was a front for booze, just as everyone knew what the twinkling lights signaled three miles off the coast. Everyone living in this idyll by the ocean had a hidden cache—false bookcases, secret tunnels—and a bootlegger’s phone number. Nearly everyone led a double life. The mayor of Los Angeles had been handpicked by underworld bosses. The head of the vice squad ran his own brothel. Most of the cops in Los Angeles were on the take, and out in the Palisades they all were.

Harrison Post’s life wasn’t doubled. It was refracted, one medium moving through another. Like a beam of light warped by water, he passed through society, his truth bending into something new.

For a decade now, the country had been living in low-light conditions, in the gloaming between legality and criminality, between aspiration to wealth and actual capital, between a fantasy of America and its reality, between the bait and the switch. Two years earlier, forty thousand people in California had lost their savings during the collapse of the Julian Petroleum Corporation, a speculative oil company that turned out to be a Ponzi scheme. Had it been a sign of darker days to come? Not according to the popular new president. That March, as the stock market continued its giddy climb, Herbert Hoover gazed out from the dais to the crowd gathered at the Capitol for his inauguration and proclaimed, “I have no fears for the future of our country.”

In the Villa dei Sogni, a small, secure outpost of the Clark empire, fear was inconceivable. If there were whispers, what of them? What if the neighbors in West Adams complained about Harrison’s parties? Not the luncheons—the other gatherings, the ones that happened late at night. What if the district attorney’s office paid an unwelcome visit? Such matters could be troublesome but also swiftly managed, for instance, with the purchase of a new home far from provincial minds, or a sudden trip to Paris. Harrison wasn’t oblivious to the rumors, but they were of little concern. Whatever his past had been, it didn’t matter in 1929, because in that moment Harrison Post was, in fact, who he appeared to be, who he was meant to be—a man of wealth and refinement. With money, power, and status, he knew he was safe, not just from detractors and gossip but also from the swerves of fortune that sent others scrambling.

That summer everything was still possible. The Dow had climbed more than three hundred points and could go higher. A bootlegger could become a man of class, the way James Gatz became Jay Gatsby. Like Harrison Post, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age creation was known for his beautiful clothes, ritzy parties, and whispered crimes. Of course, Gatsby was a character in a book and Harrison a man in real life, but they were both part fiction, author and invention alike.

In a state named for a mythical island, in a town named for angels, in a house named for dreams, Harrison Post fashioned a glittering and protected world. The house, the furniture, the books, the car, the money—all of that was real. So was the sky above, same as the ground below, and the surf crashing against the sand.

Another cigarette. The waves were always louder at night, but then we listen better in the dark.

__________________________________

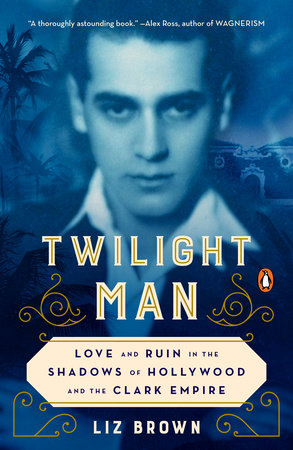

Excerpted from Twilight Man by Liz Brown. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Penguin Books. Copyright © 2021 by Liz Brown.