Poet Evie Shockley’s 2018 poetry collection semiautomatic put her on the radar that reached far broader readership than most poets, if only because the collection was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The Pulitzer board described semiautomatic as “A brilliant leap of faith into the echoing abyss of language… that leaves the reader unsettled, challenged—and bettered—by the poet’s words.” In it, Shockley illustrates her broad capacities in both topic and form. One poem that lingered (and lingers) in my mind was a multiple choice “quiz” of sorts, regarding a white cop’s attack on a Black teenaged girl at a pool party in a gated community. She poses to us:

the girl’s cries sounded like:

(a) the shrieks of children on a playground.

(b) the shrieks of children being torn from their mothers.

the protesting girl was shackled like:

(a) a criminal.

(b) a runaway slave.

It is unsurprising, considering her capaciousness and inventiveness as a writer, that Shockley has been writing intelligent and interesting work for years. Her first collection came out in 2001. She used to be an environmental lawyer, after which she earned her PhD. She has a book of scholarship about the Black Arts Movement that interrogates notions of what defines “Blackness” and aesthetics (and who decides). She writes everything from sonnets to prose poems to concrete poetry.

In short, semiautomatic is not when her aesthetic and intellectual landscape “took off,” and (lucky for us) it’s not where it has landed either. Her most recent collection suddenly we, just out from Wesleyan University Press, attends to many themes but, above all, a sense of dialogue—with other writers, artists. Much of the book engages with ekphrasis or, at least, a kind of conversation with visual work. Pieces from Willie Cole’s Beauties series are particularly remarkable, as the book includes several of the images, which Cole produced by flattening ironing boards, inking them, and putting them through an etching press.

The results echo the famous cross-section of the Brooks slave ship, with each board given the name of a woman—attending to the fact that these operate as a kind of palimpsest between enslavement and endless domestic work after liberation. As Shockley writes in one of these poems, “read flatly, // you’re the map of being pulled / in two directions at once.” In one of Shockley’s poems entitled “what does it mean to be human?” she gives us a kind of answer: “something vast we seek to squeeze into a small box.”

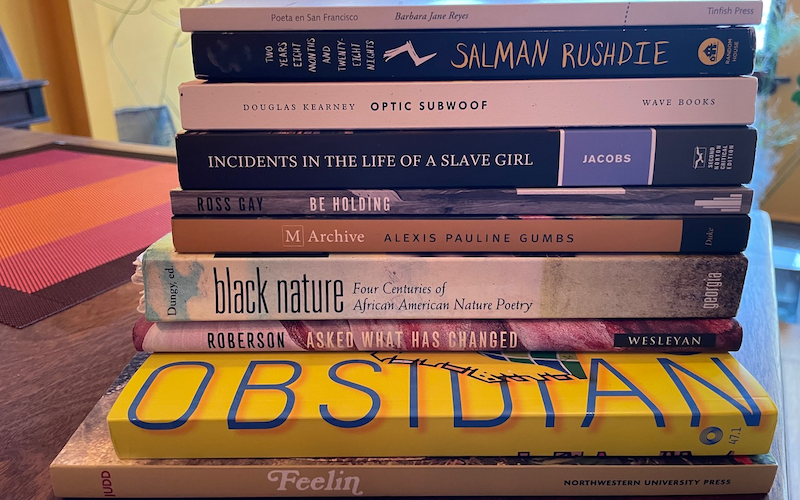

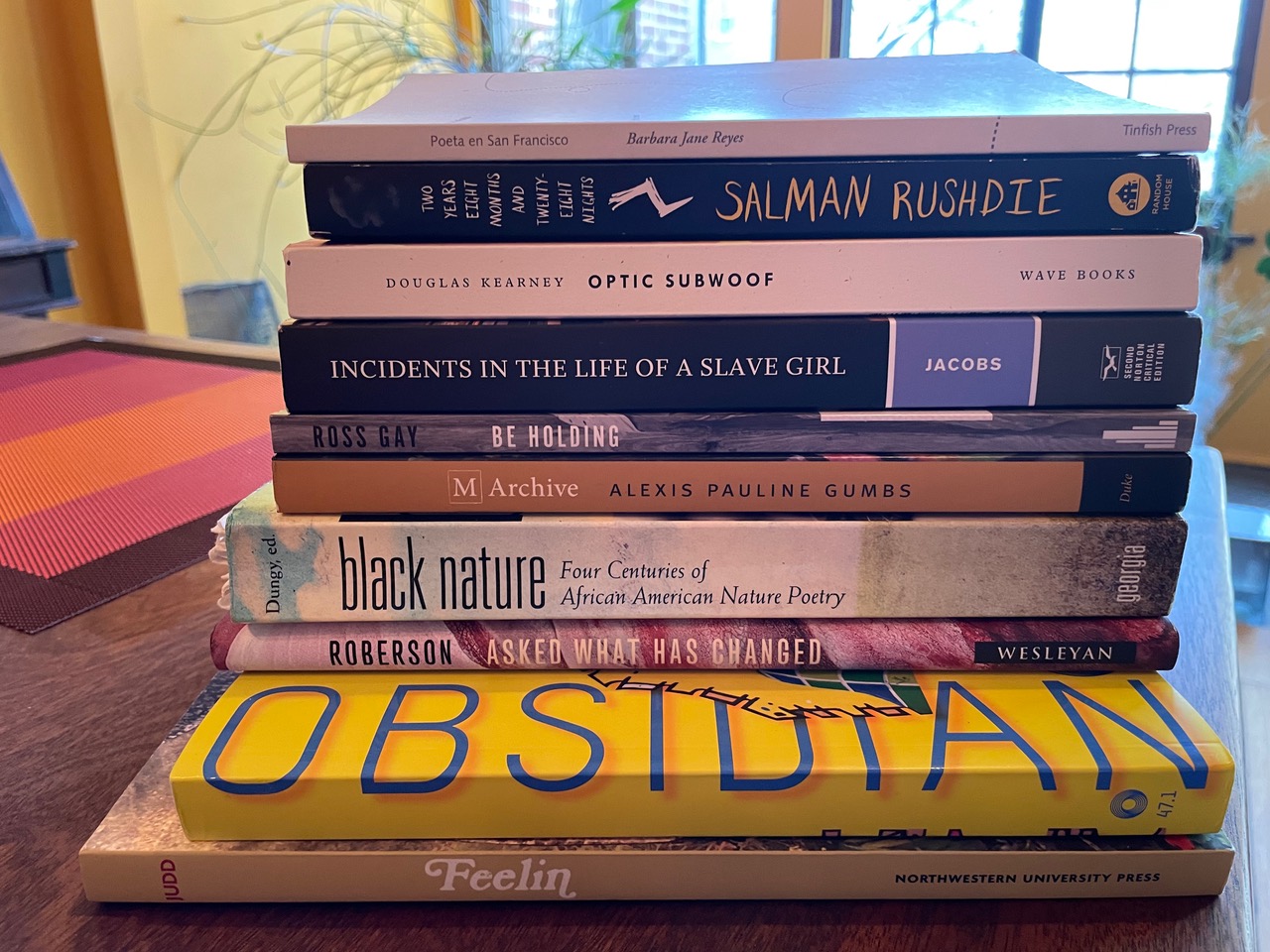

Regarding her to-read pile, Shockley tells us, “After spending my fall immersed in theory for my Black Feminist Poethics course, this semester it’s nearly all poetry, all the time. This stack represents a decent snapshot of what’s currently in the rotation—what I have been / am / will be teaching, writing on or with, thinking about, and simply enjoying within about a 2-3 week window—rapidly gathered up from all over the house.”

Barbara Jean Reyes, Poeta en San Francisco

Abigail Licad writes in The Rumpus of Reyes’ book, “Navigating one’s individual course is impossible without thorough knowledge of self and history, and it is precisely such knowledge that Reyes brandishes with urgent ferocity in her volume. The speaker in Poeta demonstrates an ever-expanding awareness that doggedly explores, interrogates, positions, and repositions the enlightened self amid overlapping contexts of history, culture, language, race, gender, socioeconomic class, and geopolitics. ‘[W]hat may be so edgy about this state of emergency is my lack of apology for what I am bound to do,’ writes Reyes in the prologue…Through incisive and uncompromising verse, Reyes unearths the hypocrisy at work in exalted American democracy as considered against the United States’s ongoing imperialist undertakings and strategic exploitation of other countries which can be historically traced to its annexation of the Philippines in 1898.”

Salman Rushdie, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights

I want to focus on the covers of this book. The first edition, designed by Sroop feels like it has everything: lightning bolts, levitating silhouettes, birds, the author’s name like a mid-century poster. Your eye invariably moves to the center and starts to see all the things that go against the rules of nature therein. The current edition’s cover designed by Kelly Blair, has a contained intensity, forcing our eyes to move through the text of this long title, the author’s name, in the sand? cloud? then certainly cloud as we see the bolt of lightning. How it uses our eye’s impulses to move into a kind of narrative in the image is amazing. Someone is lucky to have a great cover—but two!

Douglas Kearney, Optic Subwoof

Wave Books publishes Bagley Wright Lecture Series lectures given by poets at across the country, as Wave’s Publisher Charlie Wright established the series. Previous BWLS poets include Terrance Hayes, Cedar Sigo, Dorothea Lasky. Kearney’s book is a collection of his lectures, which include titles such as “#WEREWOLFGOALS” and “You Better Hush: Blacktracking a Visual Poetics.” In her review for The Poetry Foundation, Cindy Juyong Ok writes, “Kearney is known for his bold and sometimes comic readings. This book moves behind the scenes, discussing, for example, how the timing and assemblage of his banter around his ‘miscarriage poems,’—made ‘to kill audiences’ (‘funny smacks of combat’)—created internal furies and confusions. In Kearney’s nonfiction, as in his poetry, the violences of language are many and changing.”

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

What new thing to share about a book that looms large enough in American literature that it has a Sparknotes page? While both Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass are so often taught in schools across the country, Jacobs’ story is singular in how it provides her first-hand account to the particular intersectional experiences and violences endured by an enslaved woman. One thing I didn’t know is that the book was touted by abolitionists and well-received—a surprise to Jacobs, who had written under the pseudonym Linda Brent as a means of potential protection. Despite its relative success, the book was essentially forgotten for a century—until the Civil Rights Movement refocused social attention on the source of the continual brutal oppression against which so many continued to fight.

Ross Gay, Be Holding

After winning the Kingsley Tufts for his poetry collection A Catalogue of Unabashed Gratitude, and writing a New York Times Bestseller of what he calls “essayettes” in The Book of Delights, it is clear he has little interest in resting on his laurels with this book. I find myself needing to quote myself just after reading poetry collection, from a quick review I wrote on Goodreads: In Be Holding, Gay explodes our notions of a poem, of time. In turns he expands, collapses, diverts, circles back, all to interrogate the multitudinous ways in which Black bodies take flight—with Dr. J’s gravity-defying leap as a touchstone. I had to hold my head up with my hand to take in all Gay was doing in these lines. This poem changed me.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, M Archive

In a hybrid text that is second in a “planned experimental triptych,” as the publisher states, Gumbs considers Black life at the end of the world. In her review of M Archive, author and performer Gabrielle Civil writes, “This text is clearly ambitious. More compendium than chronicle, the writing is poetic, dense, and often solemn with glimmers of dark wit. M Archive unscrolls as sacred text, refusing a simple before and after. Instead, time blurs. Before burrows into another before. Memory muses a moving spiral. Future origin stories appear… M Archive speaks truth about our catastrophic moment, how we sold out our humanity and had to recover ourselves.”

Camille Dungy (ed.), Black Nature: Four Centuries of African-American Nature Poetry

This anthology has altered the American literary landscape, if only in how it illustrates the long legacy of Black nature poetry in the U.S., and having readers re-envision the relationship between the Black American diaspora and the land. In her introduction—which I struggled to excerpt as it’s all mic drop quotable—Dungy writes, “Many black writers simply do not look at their environment from the same perspective as Anglo-American writers who discourse with the natural world.

The pastoral is a diversion, a construction of a culture that dreams, through landscape and animal life, of a certain luxury or innocence, is less prevalent. Rather, in a great deal of African American poetry we see poems written from the perspective of the workers of the field. Though these poems defy the pastoral conventions of Western poetry, are they not pastorals? The poems describe moss, rivers, trees, dirt, caves, dogs, fields: elements of an environment steeped in a legacy of violence, forced labor, torture, and death. Are these not meditations on nature?”

Ed Roberson, Asked What Has Changed

Shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize, the judges state of Roberson’s Asked What Has Changed, “Poised between the vertical forces of social inequality and racial injustice, the horizontal sprawl of ghettoized urban growth and environmental degradation, and the temporal trajectories of a glacial past and a climate-changed future, these poems position a poetic eye attuned not only to seeing, ‘but with understanding sight.’ Through inventive language that moves with the sonic beauty and unpredictability of lake breakers, or wheeling swallows, Ed Roberson’s Asked What Has Changed is a challenging and urgent interrogation of and reckoning with the history, violence, and revelatory inevitability of interconnectedness between humans and nonhumans.”

Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora (vol 47.2)

Initially founded in 1975 by Alvin Aubert, Obsidian (which “appears sans italic to highlight the full publishing platform”) has undergone a series of transitions and transformations. Its mission: “Obsidian cultivates, through publication and critical inquiry, Black imagination, innovation, and excellence—supporting Black, African, and African Diaspora creatives globally.” This particular issue includes poetry from Douglas Kearney, fiction from Kiara Lowe, nonfiction from Shanna L. Smith, art from Mary Finney (just to name a few).

Bettina Judd, Feelin: Creative Practice, Pleasure, and Black Feminist Thought

I loved seeing Shockley’s own wonderful words praising this book, so I have to share them: “Bettina Judd works with every mode of writing and artistry at her disposal, offering an alternative, Black feminist genealogy of affect theory that centers Lorde’s emphasis on embodied knowledge and reads Black women’s art practices for counternarratives to death-dealing Enlightenment intellectual traditions. Feelin lovingly amplifies what Black women’s ecstatic vocal traditions, (a)theological re-visionings of the Bible, and over-seen yet under-heard articulations of rage have to teach us about the life-saving uses of the erotic and the epistemological power of grief, anger, and joy.”