From essays to interviews, excerpts to blog posts, reading lists to poems, we publish around 500 pieces a month at Lit Hub. And while we are proud of all of the 6,000+ pieces we’ve shared in 2022, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of the features we loved best on Lit Hub from this past year.

John Keats on Film: Considering Jane Campion’s Exquisitely Rendered Bright Star

by Lucasta Miller

Before Jane Campion was beloved for Power of the Dog, she directed the best literary biopic ever: Bright Star—the story of the last two years of the life of John Keats (played by Ben Whishaw) and his romantic relationship with Fanny Brawne (played by Abbie Cornish). Lucasta Miller—who literally wrote the book on Keats—pens a wonderful essay where she does what no Wikipedia deep dive ever sufficiently could: she lets us know the veracity and accuracy of the biopic, while at the same time reveling in the adaptation and appreciating its artistry. It’s a must-read essay for anyone who loved the movie, and a call to go watch it if you never have. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Seema Reza on the Joy of Being (Completely) Alone

by Seema Reza

For two glorious years, by the miracle of reduced rent at the height of the pandemic, I had the luxury of living alone. It was a freedom I had never known before: I lived in robes and blasted the Moulin Rouge soundtrack as I made midnight spaghetti, and I wasn’t at all embarrassed when I set off the smoke detector while attempting fried eggplant. For those of you who savor this feeling, or who hope to have it someday, I recommend you read Seema Reza’s incredible essay. She starts with a haunting game of pretend: not playing House, but playing Apartment—a dream of solitude, cemented in her spirit when, at the age of thirteen, she reads Sandra Cisneros’ fierce poetry of independence.

From here, we follow the writer through her marriage and the births of her children; we feel the weight of her family’s expectations, the walls closing in. Seema Reza escapes into Apartment once again, then to a writing program, where she is reminded of who she had wanted to be. She goes home and moves out and becomes that person again. It’s so rare that we take the reins back in our lives, and it is an utter delight to cheer Seema Reza along as she does. This essay is brave, and it is honest—the kind of thing you can write only when you are completely alone but at home with yourself. –Katie Yee, Associate Editor

The Order of Things: Jennifer Croft on Translating Olga Tokarczuk

by Jennifer Croft

Jennifer Croft is a translator at the very top of her game, so it was a privilege and an honor (but mainly a delight) to get a window into how she does it. And she does it frequently for no less a writer than 2019 Nobel Laureate Olga Tokarczuk. Good translation can sometimes seem as much alchemy as it does art, but in this generous essay Croft pulls back the curtain on her decision-making process, revealing the particular mix of intuition and erudition she applies to her work. And yet somehow it still feels like magic. A must-read for anyone who cares about the elusiveness and beauty of language. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Remembering the Kindness and Master Storytelling of Editor and Author George Hodgman

by Gabe Montesanti

If you don’t know (or know of) the late author and editor George Hodgman, Gabe Montesanti’s essay about crossing paths with him at a pivotal moment in her life and writing career is still an incredibly moving story about teachers, learning to tell your life story, and how crucial it is to be seen and encouraged by a writing mentor. If you are familiar with George Hodgman, author of the remarkable memoir Bettyville, then the piece is even more affecting: Montesanti perfectly captures his humor, kindness, and talent, and the literary community’s loss of him far too soon. Beyond a memorial, though, Montesanti’s brief piece also manages to be a tiny künstlerroman—a story of starting over, becoming an artist, and that glorious moment when all the pieces come together. (And also, roller derby.) –Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

Seeking a New Story: On Sobriety and the Stories We Tell About Ourselves

by Sara Martin

It’s so easy for writers—forever implored both to mine our trauma for content and to cultivate a unified brand—to fall into a pattern of retelling the same stories about ourselves. Sara Martin’s lovely, searching essay about the narrative of her sobriety explores the allure and the danger of centering drinking as the main character of her story—both as a writer and a human. “The sobriety narrative is appealing in that it organizes life into a tidy before and after, the epitome of a transformation story, powerful proof of the capacity to change,” she writes. Her essay is an excellent reminder of the rewards of digging into the mess. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

All Tomorrow’s Fables: How Do We Write About This Vanishing World?

by Daegan Miller

Our best writers are those who pay the closest attention: to their inner voices, to the people around them and, of course, to the world at large. Daegan Miller is one such writer who, with an unlikely mix of grace, realism, and honesty, pays wonderfully close attention to the natural world and our place in it. In what is ostensibly an essayistic review of The World As We Knew It, an anthology of elegiac writing about our changing planet, Miller grapples with the responsibilities of the writer in the face of so much global loss, wondering aloud what responsibility the writer has to explain, to bear witness, and to mourn. We should all take his closing lines to heart, whether we’re writers or not, and…

…stay close with the trouble, down close next to the troubled earth and the troubled lives lived upon it, down where our best dreams and art come from, down where our humanity lies.

–JD

If They Want to Be Published, Literary Writers Can’t Be Honest About Money

by Naomi Kanakia

Any conversation about publishing is never far from a conversation about money: the two exist in tandem, unfortunately, because of the interminable fight for fair wages the industry workers find themselves in. It’s almost viewed as a rite of passage to be paid so poorly, justified by the fact that higher-ups also went through it, and because it means one is getting to work in an industry they’re passionate about, one that looks shiny and enviable from the outside. Authors themselves also struggle to make ends meet: many advances for literary fiction and nonfiction are five figures or lower, not enough to live on by any means, barely enough to supplement whatever day job they have.

But barely any books these days are centered around the topic of livelihood and scarcity, an issue that both publishing employees and authors are theoretically familiar with—where are these books, and if they’re being written, why aren’t they being published? Naomi Kanakia gets to the core of this question, ruminating on the audiences the publishing industry relies upon, both the “high brow” and the “middle brow”, different in their cultural backgrounds and tastes, but both necessary for the success of the book and its sales; as Kanakia says, “they need to write for their fellow students in the MFA and for those students’ mothers.” Kanakia does a deep dive in the history of the literary novel, the audience’s fluctuating readiness to read about money and work, and authors’ unwillingness to either fess up to privilege or reveal the truth about the hardships they’ve faced. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

On the Coen Brothers’ Bitter, Brokenhearted Noir, Miller’s Crossing

by Olivia Rutigliano

“Miller’s Crossing… is full of unbearable wetness—not simply because it is about Prohibition, but also because it is so often about liquid. It’s a film full of rain, tears, phlegm, vomit, blood. Its opening sensations… ignite such an unpleasant cacophony of babbling fluids that you might feel sick by the time the scene ends.” This brilliant reflection on Miller’s Crossing (written in honor of the film’s Criterion Collection re-release earlier this year) by Olivia Rutigliano captures so much of what I love about Coen Brothers’ 1920-era “gangster ballad”—from its playful subversions of classic noir tropes to its dreamy woodland cinematography, from the messy physicality of its protagonist to its Danny Boy-scored signature set piece. Rutigliano’s movie essays at Lit Hub and CrimeReads are always essential reading, but this ode to Tom Reagan and co. is my 2022 favorite. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

We’re All Just Extras Here: Wandering the Back Streets of Old Hollywood

by David L. Ulin

It would be hard to find a better contemporary American writer of the modern city than David Ulin. So it was good luck for us (and bad luck for him) that circumstances saw him dislocated in his beloved adopted home of Los Angeles, wandering the church-heavy streets of Hollywood:

Since the end of August, we had been living out of suitcases, driving back to our place on a daily basis to retrieve the mail. Now, it was December, and there was no end in sight. The sensation was of being rootless. The sensation was of the conditional.

It is in that rootlessness, in his “days and nights in Hollywood,” that Ulin comes round to a literary disquisition on the not-at-all well remembered Southern California writer, Horace McCoy, who gave us the source material for They Shoot Horses Don’t They? But, according to Ulin, McCoy should be talked about more for his 1938 novel I Should Have Stayed Home.

But this isn’t an essay about McCoy. Or Hollywood. Or just about McCoy and Hollywood. Because maybe a good essay—like any city worth remembering—isn’t about any one thing but many; maybe we are better off—in writing, in wandering—when we let our subjects discover us. And this has always been Ulin’s gift as a writer (and perhaps as a wanderer): he makes sure he’s ready for when his subjects discover him. –JD

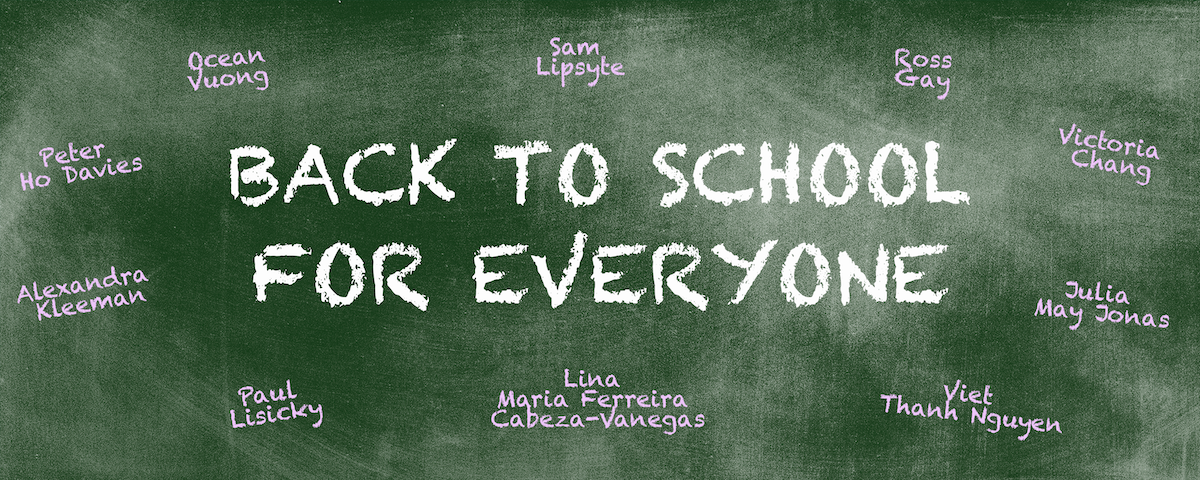

Back to School for Everyone: (Free!) Syllabi from Some of Our Favorite Writers

Featuring Victoria Chang, Julia May Jonas, Sam Lipsyte, and More

As someone who will forever and always miss school, I was thrilled that ten writers whose work I deeply admire offered their own syllabi—complete with reading lists and a mini-essay on why they love teaching the course—for Lit Hub readers. Are you ready for this lineup? Victoria Chang on ekphrastic poetry! Julia May Jonas on the literature of obsession! Paul Lisicky on multigenre experiments! Peter Ho Davies on reading about writing! Lina Maria Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas on speculative women! Alexandra Kleeman on place! Viet Thanh Nguyen on writers and the world! Sam Lipsyte on sports writing! Ocean Vuong on hybrid poetry! Ross Gay on lyric research! That’s basically an MFA, no? –ES

No Place You’d Want to Go: On Writing About Flint

by Kelsey Ronan

Kelsey Ronan grew up in Flint, Michigan—a place known for the General Motors factory, Michael Moore’s documentary, some references in Toni Morrison’s novels, and the bottom of internet lists for the worst cities in America. For Ronan, though, Flint is a home she can’t escape, its stories more complex than what people quip to her at an MFA party. Her life has been marred by tragedy—”I’d applied to MFA programs because my partner had died of a drug overdose and I wanted badly to get out of the city”—but somehow despite her past—or maybe because of it, she has the cool insight and deft ability to describe a city layered with meaning. –EF

We Need to Reckon with the Rot at the Core of Publishing

by Elaine Castillo

It’s no surprise that there is a litany of deeply rooted problems with the way books are published, packaged, edited, and covered—and Elaine Castillo is taking everyone to task and imploring us to decenter whiteness. Yes, there has been a recent push for “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” Yes, the industry has more or less rallied behind this idea of “representation.” But, as Elaine Castillo points out, it’s all empty gestures if readers are just searching for tokenized trauma and if employers aren’t willing to genuinely engage with their internalized white supremacy. The writer takes us through her own love affair with reading, the way her father taught her to read deeply and critically: “We read a lot of white people. But we didn’t read them with a white-centering view; we didn’t read them like those books and the worlds in them were the only ones that existed, or mattered.” If you work in publishing, you need to read this. If you’re a writer, you need to read this. If you’re a reader, read this. –KY

How Being Broke (and Taking My Top Off) Made Me a Writer

by Deborah E. Kennedy

Two kinds of stories I love in equal measure: The ones that are honest about fitting writing in around the work of staying alive in a capitalist country with no social safety net, and the ones that detail the particular strangenesses of said work. Deborah E. Kennedy’s sardonic, hopeful essay, about her “brief time as a Gloria Steinem bunny-era wannabe” and the peculiar gift of being broke, is a beautiful example of both kinds of stories. It’s also a love letter to the power of stories to help us make sense of even the grimmest circumstances—a conclusion which, in Kennedy’s hands, feels both earned and true. –JG

Best American Male: An Essay About Masculinity. An Essay About Power.

by Rebecca Hazelton

Rebecca Hazelton’s incredible essay about the causes and effects of toxic masculinity is an exercise in controlled accretion. With the precision of a poet, Hazelton layers image upon image, working in a cadence that lures the reader into what is almost a collective self-interrogation: Why do we let boys become bad men? Why do we look the other way when those bad men wield their power? Why do we think their art expiates their sins? Hazelton doesn’t answer these questions—at least not explicitly—but rather challenges us to answer them for ourselves. A brilliant piece of writing. –JD

Generation Amazing!!! How We’re Draining Language of Its Power

by Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza

Rather than being a polemic against naughty uses of the English language, Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza’s amazing, incredible, surreal article unpacks the trend toward the hyperbolic in contemporary speech, and what it might say about us. “If we’re talking this much, it might be that we’re desperate to exist,” she writes. “If we’re slinging around words like amazing and incredible and surreal, it might be that we’re looking for these things. If we are Generation Hyperbole, it is because we are so desperate to feel something good and tremendous—we’re constantly reaching for something beyond. We want to feel awed, we want to be in touch with something dreamlike, we want to see things that are really beautiful, we’ve only forgotten where to find them. But we’re looking for meaning, you can see it in our language.” Feels true to me. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

I Fight to Learn What it Means to Feel Calm

by Laura van den Berg

“There is a process, in other words, just as writing a book demands a process. Something about being in the thick of both these processes—one very internal but also bodily, the other very physical but also with its own intricate psychology—has turned out to be deeply generative. Like locating the other half of an equation, one that I did not know was missing until I found it.” As part of Lit Hub’s new When I’m Not Writing series, Guggenheim Fellow (and author of many wonderful books, including eerie masterpiece The Third Hotel) Laura van den Berg wrote about her recently discovered passion for boxing, a sport which she took up for the first time in 2018 and which now plays a significant role in both her physical and mental life. This essay is a brief but lovely meditation on finding serenity, and self-confidence, inside the storm of the boxing gym. –DS

“There’s No Story to Tell About Swimming.” Madeleine Watts on How to Quiet the Mind

by Madeleine Watts

I’m always relieved to hear about writers’ physical pastimes, to realize nobody can sustain a “life of the mind” all the time. It’s writers especially who usually need to get themselves out of their head, apt as they are to rumination and analysis: a gift when it’s leading to incisive words on the page, but a curse when it’s turned inward, turned unkind. I loved hearing about Madeleine Watts’ swimming practice, the treasure of it being “anti-thought,” reducing her to a body in the water, moving through space and time. A meditation, a ritual that she can replicate wherever there’s water, she’s found her reprieve from herself: would that we all be so lucky! –JH

The Mystery of the Indestructible Beetle

by Lulu Miller

In this introduction to Orion Magazine’s new The Book of Bugs, Miller—the author of the truly brilliant Why Fish Don’t Exist—does what she seems to do best: chart a fascinating scientific moment (in this case, a man named Jesus Rivera’s obsession with an indestructible beetle); pair it with a rumination on the relationship between the writer and the person (you) processing this information, enjoying it, understanding the elements of suspense and discovery and working alongside Miller to uncover the true story; and weave in some heartbreaking personal anecdote. The result is a perfect capsule of an essay—which is both a great introduction to the anthology, which features writing from Brian Doyle, Jane Hirshfield, Linda Hogan, Robert Macfarlane, David Quammen, and E.O. Wilson, plus is just another reminder that you should probably pick up Why Fish Don’t Exist if you haven’t read it yet. –EF

Cranly’s Arm: On Finding and Seeking Gay Desire in Joyce

by Paul McAdory

“Seeing it here, where no one else seemed able, seemed more valuable than looking where others had looked and found it and saying, ah, yes, there it is, gay subtext.” Paul McAdory’s gorgeous essay doesn’t seek to convince its reader of the existence of gay subtext in the work of Joyce (though I was convinced)—rather, it dwells in the preciousness and power of the discovery. It’s a thrilling blend of literary criticism and personal history, and a testament to the joy of forgoing systemic analysis in favor of cutting a thread “where convenient, to twirl it about my finger, slip it in my mouth, and swallowing.” After all, why else do we read? –JG

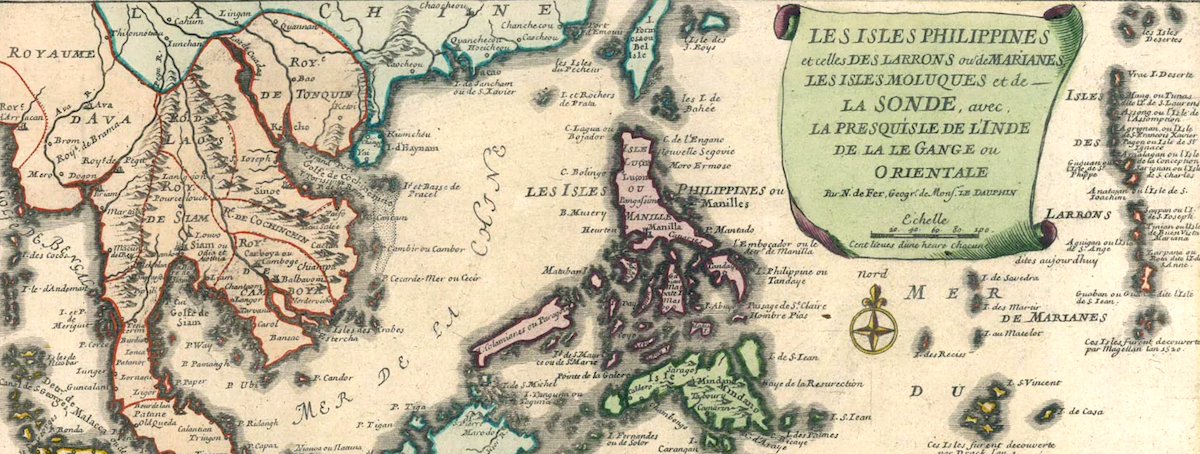

The Alchemy of Language: Ina Cariño on Naming, Claiming, and Protecting Ancestral Land

by Ina Cariño

In this gorgeous fragmented essay, Ina Cariño takes us on a journey: from a Catholic Montessori school in the Philippines to the aisles of K-Mart in the US. They trace the story of their othering, the way it feels to be dropped into a new environment and to reach for the concept of home. Home is a funny, slippery thing, particularly for this writer and their family. In this essay, we are let into a bit of family legend: back in the 1800s, their ancestor defended Baguio against imperialist rule, eventually taking the land dispute to the US Supreme Court. Weaving in Filipino folklore and the Grimm’s fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin, they write about the transformative power of names, the way an etymology can reveal truth or trickery. Ina Cariño is a poet, and that’s clear from the way their sentences curl and cut. Just listen to this: “But in my own confused circling, I name myself Other, spell myself into being, yearn for a future that spells me correctly.” It’s a beautiful piece that touches on Indigenous rights and immigration, the stories we pass down, and making a name for yourself. –KY

Maryse Meijer on Training to Be a Bullfighter (Who Will Never Fight Bulls)

by Maryse Meijer

As a hobby-less person, I’m really digging Lit Hub’s new series (spearheaded by Katie Yee) When I’m Not Writing, in which writers geek out about what they enjoy other than, you know, writing and reading. They’re all fun, but the first line of this one really got me: “Every Saturday, from ten to noon, I pretend to be a bull.” Maryse Meijer, “a vegan obsessed with animal rights,” goes on to describe the practice of torear—which I had zero context for aside from The Sun Also Rises—and why she’s drawn to an activity she finds as repelling as it is fascinating. The answer has to do with both writing and living, like all my favorite craft-adjacent essays. –ES

Rogue, Hero, Icon: On Paul Newman’s Taste for Literary Adaptations

by Nicole Miller

This is a fascinating examination of Paul Newman’s penchant for, and interpretation of, American literary archetypes of masculinity, focusing both on the way Newman’s seductive presence and irrepressible magnetism shaped audiences’ sympathies, and how the actor’s oeuvre “traces our shifting cultural allegiance to winners and losers.” Miller calls Newman “an uncanny avatar of male ambivalence about cramped civilization,” contrasting his steady home life and laudable civic persona with the “rogue individualism” that so often characterized his on-screen persona: “Throughout his films, Newman manifests an uneasy rapport between the sentimental dream of assimilation—into society or normative family life—and the seductions of alienation.” –DS

The Unexpected Gifts of Writing About Grief

by Jacquelyn Mitchard

It was nice to hear someone say straight up “I believe sad stories matter more,” because that’s been a secret opinion of mine for a long time—I haven’t written a happy song in my life, and I don’t know that I will or even can. Joy isn’t the emotion that sends me to the page, because it always appears more complete, more solid than pain: stones don’t feel unturned with joy, it just feels like itself. I want to revel in the experience of living when joy is occurring, whereas deconstructing pain can feel like an antidote. Jacquelyn Mitchard recognizes this tendency in herself, and contemplates why; she ends on a graceful note, resolving that we can find hope in pain, both one’s own and others’, in the sheer fact that it was survived. –JH

First lines of classic novels, if no one had childcare.

by Jessie Gaynor

Here’s a confession: I almost never like “parent humor.” But as a new parent with a full time job and very little childcare (thanks for nothing, America) this specimen, written by Lit Hub’s own Jessie Gaynor, actually made me snort into my thrice-reheated coffee, and didn’t make me feel like I just wanted to go to sleep and/or die. (The comments are also funny . . . in a different way.) –ET