Child 1: Mmm, yes.

Journalist: What did you do?

Child 1: I did a little looting, but I gave it back.

Journalist: You gave it back?

Child 1: Yes, but I think it’s all right to loot some people if they’re gonna stay open. But to burn it down, no. I caught a man in a Hahn’s shoe store trying to burn that down, and I put it out.

Journalist: You put out the fire?

Child 1: Yes, sir.

Journalist: What do you think? Were you involved in any of this looting?

Child 2: Yes, sir.

Journalist: What did you take?

Child 2: Oh, a safe and a couple—

Journalist: You took a safe?

Child 2: As a little safe that you put money in, and a couple more stuff. And I think they should have had the riot, but they shouldn’t have—

Journalist: Why should they have had the riot, young fella?

Child 2: Since Martin Luther King got shot, everybody seemed like they wanted to riot. I say that. I’m not saying that they should have had it, but if they did have the riot, they shouldn’t have burned.

Vann R. Newkirk II: The burning of Washington city, in 1814, by the British felt to many like the end of an era, the beginning of a new one. That sense of unease motivated our national anthem, the “Star Spangled Banner.” After fleeing Washington and seeing American troops then beat back the British in Baltimore, Francis Scott Key felt the triumph of the dawn’s early light.

One hundred and fifty-four years later, D.C. burned again. In the middle of it all, people tried to step back and think about what it meant for this country, this democracy. They tried to find meaning in the chaos of those spring nights. There were big, serious news specials and lofty speeches in the halls of the Capitol. But the recollections that interest me most come from a group of children at the heart of the riots. In the Cardozo district, primary and junior-high-school teachers started asking their students what they thought and documenting their replies.

Teacher: Here’s an interesting comment from another fifth grader, who is talking about Martin Luther King: “His dream wasn’t like most dreams. It wasn’t just him in the dream. He wanted everybody in his dreams. He wanted to take us to the promised land with him. Now he has left for the promised land, and we have to follow.”

Newkirk: Kids as young as 6 and 7 responded to prompts from their teachers about what they had witnessed in the streets, through drawings, poetry, through essays. Reporters from ABC were so captivated by this experiment that they came to see it.

Teacher: When we ask children the saddest thing that they saw, one child in the first grade responded that he was very sad when he saw three Negro boys beat up a white man and stab him. And then we asked also, “What was the happiest thing that you saw?” And children said, “People helping each other, giving them food and things of this type.”

Newkirk: The drawings are vivid and incredibly raw. There’s one drawing of a grocery store, a Safeway, where people are lined up outside, carrying food away. One woman has a speech bubble that says, “I got a lot of meat.” A guy answers her and says, “Let’s get more meat.” Across the street there’s a police car with its own speech bubble: “I will shoot tear gas.”

Teacher: I really think the children did a better job with the drawing of pictures. Because of the area where these children lived, many of them could see the flames coming from their houses, or they lived nearby where things were burning.

Newkirk: There are drawings of the first rocks being thrown at the Peoples Drug Store, images of soldiers, crayon pictures of fires. There are sketches of the soul brother signs people put in their windows, like lamb’s blood marking homes during Passover. One of the most haunting pictures is a pen drawing of the G. C. Murphy’s store on 14th and Irving. It shows the store burned and collapsing. There’s a body inside, trapped under the rubble. The newspapers say that two teenage Black boys died there in the fire. One was never identified. There’s a Bed Bath & Beyond there now.

Some teachers asked their kids a simple question: How did they feel? A few said they just wanted to be in clean, safe neighborhoods. Some said they were still sad, or still angry, or just trying to hold on to King’s message of nonviolence. Some hated the looting; some defended it. The answer that sticks with me is from one student who didn’t care about any of that. They wrote, “Right now I would like to forget about Black Power, soul, and all the burning of stores. I would like to forget about 14th Street.”

***

Journalist: Late last night, Washington’s deputy mayor, Thomas Fletcher, said that the city was so quiet that it's eerie, like a science-fiction movie. This morning, too, is quiet, sunny, cool. The jonquils blooming, a fresh breeze scattering the blossoms of cherry and mock orange and dogwood. But unlike other crisp spring mornings, soldiers are walking post up and down the avenues and streets, walking in pairs along F. One walks alone at the intersection of 14th and Pennsylvania Avenue. But there are 24 soldiers to the block …

Newkirk: In Black D.C., April 7 felt like a time for forgetting, if just for a moment. People were cleaning up shops and homes, sweeping glass and bricks and charred wood from the streets. Church bells rang as people walked to services to lay down their branches for Palm Sunday.

Journalist: Normally, this would be a special day for churchgoing, Palm Sunday. Today, there was another reason: a national day of mourning for Martin Luther King.

Newkirk: Some of the shoes that crunched on sidewalks were nicer than usual. There were brand-new stockings with no runs, dresses and sweaters that fit, with no patches. If you squinted and ignored the soldiers, maybe you could believe this was just like any other holiday. But in pretty much every church in America that Sunday, the sermons were a little different.

Preacher 1: Oh, Heavenly Father, be mindful of the soul of Dr. Martin Luther King, who sacrificed his life for the sanctification of thy holy name.

Preacher 2: Martin Luther King’s death deprives America of one of its outstanding spiritual leaders.

Preacher 3: Are we satisfied to pass along the poverty as we go along our palm march? Or do we want to march down the road of prosperity for all men?

Ralph David Abernathy: They thought that they could kill our movement by killing you, Martin. But, Martin, I want you to know that Black people love you.

Newkirk: In Atlanta, at West Hunter Street Baptist Church, Reverend Ralph David Abernathy gave a sermon directly addressed to his old friend. But it was also aimed at what was going on in places like D.C. He tried to reconcile what had happened on the streets with the nonviolent philosophy he still believed in.

Abernathy: It may seem that they are denying our nonviolence. But they are acting out their frustration. Poor people have had a hard time during these difficult days.

Newkirk: Palm Sunday in the church is supposed to symbolize the ultimate victory of Jesus over the material world, and to foreshadow his role as the spiritual conqueror of sin. In his sermon, Abernathy recast King as redeemer—conqueror of the sin of racism.

Abernathy: What we know, Martin, because we love people, is that after the bidding of frustration, there will be the need for reconciliation.

Crowd: Mm, hmm.

Abernathy: There you will be invisible, but real. Black and white will need you to take them from their shame and reconcile them into you and onto our master, Jesus Christ.

Newkirk: If there would be any reconciliation in D.C., its time was due. It wouldn’t just be a reconciliation between Black and white, but between two visions of what the city was. D.C. was supposed to be a model city for its thriving Black middle class. It was a city that was geographically in the South but seemed to rise above Jim Crow. There were Black doctors and Black lawyers and even a Black mayor (even though he wasn’t elected). For many Black people, life in D.C. had seemed like a safe haven, a bubble. But now, just like the kids in Cardozo schools, people in D.C. were forced to wake up from their dreams.

***

Newkirk: Part 6: “Kingdom.”

***

Roland Smith: My father, my grandfather, and my great-grandfather were born in the district. Actually, I’m a fourth-generation Washingtonian.

Newkirk: Wow. Fourth generation. I don’t meet a whole lot of those.

Smith: Yeah. It’s rare.

Newkirk: What neighborhood?

Smith: Well, we started off in northeast—far northeast—and then northwest. I went to Calvin Coolidge High School.

Newkirk: When I talk to old-school Washingtonians, they have a way of talking about “old D.C.,” before the riots, about what was lost in the fires. Roland Smith was born in D.C., and his family roots there go way back. Family legend has it that they moved to the city from a plantation in northern Virginia, but nobody really knows. The point is, Roland is D.C.

Smith: I think about D.C. back then as a sleepy southern town.

Newkirk: He’s got classic memories of just riding around D.C. on his bike as a kid. It’s never been a really big city, but it felt smaller then. There were no blocks dedicated to lobbyist offices, fewer condos, less traffic. Outside of government buildings, most of the town was residential. Roland was born in one of the first public-housing developments for Black people in all of Washington.

Smith: And that was at a public-housing unit, Langston Terrace Dwellings in northeast D.C., right on Benning Road.

Newkirk: Roland’s family was built on a foundation of civil service that was really only possible in D.C. His grandfather was a messenger on Capitol Hill who also tended bar sometimes for Hill staff. Roland’s mother was a government secretary. His father served in World War II, and as a disabled veteran, worked three jobs to save up enough money to buy a house.

Smith: It was a big deal in our family because not very—most of our family rented their houses or rented their apartments. They didn’t own.

Newkirk: For the family, it was a step up into a life they’d always dreamed of. The house became a way station for family members from all different sorts of situations. It was the kind of pathway that lots of Black families with deep roots wanted to follow. Taquiena Boston’s family was one of those.

Taquiena Boston: My mother grew up in southwest, which they refer to as “Old Southwest.” That was a neighborhood where people were in and out of each other’s houses. Your door was kept unlocked.

Newkirk: Like Roland, Taquiena also grew up in northeast, in apartments in Brentwood. Her family didn’t really have money. Her dad drove trash trucks. But still, her parents had plans for their kids. Taquiena’s mom took her and her younger sister to go get library cards as soon as they could read. They learned nursery rhymes. They read The Wizard of Oz.

Boston: My dad brought home some Encyclopedia Britannicas that were going to be discarded. They all had the front covers taken off, but he brought them home for me to have a set of encyclopedias.

Newkirk: Taquiena’s family didn’t live too far from the H Street Corridor, where Vanessa Lawson and her brother Vincent were born, the area where they started their first hustles raking leaves and carrying groceries.

Vanessa Dixon: Oh, my God. It was wonderful. I wish I could have raised my kids or my grandkids—they could have been raised in a neighborhood like I was. Everybody knew everybody’s name. Everybody knew everybody’s business. Everybody watched each other’s kids.

Newkirk: Vanessa can remember the details like it was yesterday. Before her parents split, they lived off H Street. They were behind the strip of Black businesses and shops. There were neat rows of breadbox houses with green lawns. Everybody went and worshiped together on Sundays, in a church right on the block.

Dixon: They had a basket full of musical instruments and you could grab what you wanted when you came in the church. And you knew, though, when you went in there, what was expected of you. Okay? So no horseplaying and none of that kind of stuff. And I got to say, everybody respected that little church.

Newkirk: You are painting such an amazing picture of life. I feel like I can put it all in my head right now. I feel like I’m there.

Dixon: I get chills talking to you every time I do. It’s just so surreal, you know? It was a good place, a good time in my life.

Newkirk: Vanessa’s parents came up from rural Virginia before she was born. They left behind a state where poll taxes were still used to keep Black folks from voting. They were drawn towards a city where Black theaters played Black movies on U Street; where families like Roland Smith’s could own houses in neighborhoods full of other Black homeowners; where maybe, just maybe, they could have the lives America promised its citizens. They were part of a wave of Black people that also included the parents of Theophus Brooks. His folks arrived in D.C. from North Carolina, before he was born.

Theophus Brooks: My mother’s from Goldsboro.

Newkirk: Goldsboro!

Brooks: My father’s from Hertford.

Newkirk: Oh yeah. I’m from North Carolina.

Brooks: Yeah, yeah. I got a lot of my cousins down there. Matter of fact, my uncle, my father’s brother, had 10 girls, no boys—10!

Newkirk: For Theophus, North Carolina might as well have been a world away. He lived in Cardozo, the Black enclave within the Black metropolis.

Newkirk: What was the city like back then?

Brooks: Oh, man, it was great. They had respectful families. You can almost leave your doors open because your neighbors could knock on the door and come on in. You know, a lot of kids ate breakfast and dinner at my house. I went over to their house. We respect everybody’s parents.

The ’60s to me, it was the best time because, in D.C., we didn’t have no racial problems. Never heard anybody call me a [N-word] because you didn’t have that in D.C.

Newkirk: It was all Black folks.

Brooks: Yeah, it was mostly Black.

Newkirk: With Theophus, it’s the same story as Roland and Taquiena and Vanessa. It’s like they’re describing a Black fairy tale. And in all of those tales, you don’t hear much about the bogeyman of Jim Crow.

Brooks: We livin’ in D.C.; we had all the rights. I mean, we didn’t think about being treated nasty because, you know, when you in this environment, you don’t think about that. I’m 73 and I’ve been in D.C. all my life. I never experienced racism in D.C.

Boston: My mother said she’d never, never have grown up feeling bad about being Black. She felt worse about being what she called “low-class.” Of course, they didn’t live around white people, right. So maybe that was why.

Roland Smith: I think that we were kind of insulated to some extent from some of that, early on.

Newkirk: For Theophus Brooks, Roland Smith, Taquiena Boston, and Vanessa Lawson, this was D.C., Black D.C. It’s what so many parents and grandparents had come to the city for, what people were still taking trains and buses to the city for: a safe haven.

Still, when the March on Washington came to town in 1963, a lot of Black Washingtonians were interested in what the speakers had to say about integration, jobs, and freedom. Roland Smith was a teenager then. He wanted to go, but his mother was afraid there would be violence. He snuck out anyways.

Roland Smith: I went to the March on Washington. So I was there. I was there listening to the stories of the marchers and what they had sacrificed to get there.

It was surreal. There were a lot of people, but there wasn’t a lot of noise. There was a reverence about the whole process. It seems to me there was some singing, and I just remember that this was something special. But I didn’t fully understand the implications.

Newkirk: You didn’t have a sense of sort of being in this historical moment?

Smith: Yeah, I think I did. I felt that more as we saw the news, you know, kind of post-march and how it was treated. And I was thinking I was just glad I was there. It was hot, though. It was. [Laughs.] It was a very hot Washington summer day. [Laughs.]

Newkirk II: When did your mother find out you were gone?

Smith: When I got home [Laughs.] later that evening. [Laughs.]

Newkirk: About 10 percent of the marchers in ’63 were native Washingtonians like Roland. It was a moment of pride for them—hosting, supporting, and marching. But for many residents, especially younger people, the march also helped highlight the truth about the D.C. fairy tale—the apparent freedom and prosperity they had, had limits.

March on Washington speaker: Brother John Lewis. [Applause.]

Newkirk: At the march, civil-rights hero John Lewis stepped up to the podium and started talking about voter disenfranchisement.

John Lewis: One man, one vote. It is the democratic cry. It is ours too. It must be ours. [Applause.]

Newkirk: One man, one vote. He was talking about the Deep South. But he was also speaking in a majority-Black city that didn’t even elect its own leaders and had no representation in Congress. There was no home rule. D.C. was controlled by a committee in the House that was full of segregationists. Washingtonians had just barely gotten the right to vote for president. For Roland and some others like him, the contradiction was glaring. How could D.C. be the Black metropolis if Black people couldn’t even govern themselves?

Roland Smith: You know, you think about things like the March on Washington and the role that that played with all the people descending upon the district. And I think, one of the issues for the district was not being able to vote. So, that was, home rule, was a big issue. And so I think that fomented some of the discontent.

Newkirk: As they grew into adolescence, Roland, Taquiena, Vanessa, and Theophus saw these contradictions more clearly. They were born in a city that had once been tightly segregated, but while they were all still kids, white folks started leaving by the thousands. They took their tax dollars and resources with them. The money moved to suburbs in Virginia and Maryland, where Black kids from D.C. were most definitely not welcome.

Taquiena Boston saw her mother’s old neighborhood paved over, by “urban renewal.”

Theophus Brooks learned to stay away from certain parts of Maryland.

For Black families like Vanessa’s, it became easier to fall down the ladder than to climb. When her parents got divorced and the kids had to move with their mother to the projects, her brother Vincent was angry about the changes.

Vanessa Dixon: My uncles and stuff came, and they packed us up and we moved. And when we got to where it was, my brother said, “All these places look alike. How are we going to know which house is ours?” kind of thing, you know. And he was the smart one. And the thing is, when we got over there and moved in, once he started learning the reality of this move, and that our new residence is in the projects—you know, the family decline—it’s like, he blamed it on my dad. So he was mad at him for most of the time after that.

Newkirk: The Lawson family found out that the paradise of Black D.C. was more of a limbo. The Black middle class was still thriving and glamorous but grew more distant from working-class spaces. The rise of television made it impossible to miss what was happening in the Deep South, and for some young Black Washingtonians, it started to shine a light on continued segregation in their own city. But the intense poverty of the ghettos was more like what was happening up north. Roland Smith says watching the riots there, in ’66 and ’67, was like holding up a mirror.

Roland Smith: Hearing about the unrest and the riots and the things going on in the South, and even in Detroit, I mean, you think about all those things that were going on back in the ’60s—early ’60s—and those were all kind of swirling in the mindset of folks.

Newkirk: What’s your family think about those? I had a big argument over the last weekend with some people who were more “don’t rock the boat” versus people who were behind it.

Smith: Oh, yeah. We had that. I mean, there was a lot of that. And I think that the divide actually started to break along generational lines.

Newkirk: D.C.’s ghettoes never did join northern cities in riots in the mid-’60s. It’s possible that the old mystique of the Black middle class and the magic of the fairy tale kept the city in place, kept hope in place, even in the teeth of poverty. That’s why King chose the city when he announced his Poor People’s Campaign. It had been planned to kick off in late April of 1968.

Reporter: There are large Negro neighborhoods here in Washington, like any major city. In fact, this is the only major city in the nation with a Negro majority, and it has a Negro mayor. There are four sections, and there are Negro middle-class sections. Washington, in many senses, is the middle-class Negro capital of the world.

Newkirk: The idea was to use the vibrant, Black-middle-class institutions as an organizing base for highlighting poverty on the doorstep of the nation’s capital. To do that nonviolently, King and the SCLC had wanted to harness whatever spirit of reconciliation had kept the city together.

But as the church bells rang after Palm Sunday services, the world began to spin again. Parishioners went back to ghettos, business districts, middle-class neighborhoods that had been burned. The fairy tale was over.

***

Newkirk: Just after the assassination, John Burl Smith had been crushed. He and other leaders of the Memphis Invaders had tried to bring Black Power organizing to the sanitation workers’ strike. They clashed with the establishment civil-rights leaders, but after he and his co-leader, Charles Cabbage, met with King in his motel room, they walked away thinking that Martin Luther King had taken them seriously. John believed it was the beginning of something special.

John Burl Smith: When we left the room, Charles and I was feeling really great, man. We had just become a part of the coalition of the No. 1 Black leader in the country, you know? That to me was as good as it gets. And when we get home, and the announcement that he’s been assassinated, it’s like everything’s fallen apart.

Newkirk: The Invaders’ last interaction with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had been back at the demonstration on March 28, which turned into a riot. King had called the meeting partly to get the Invaders under his chain of command. And he let the media know that he would be working with them.

Reporter: One of the ironies that Dr. King was killed here, is that his last few days were spent trying to negotiate with the militants in Memphis and elsewhere, hoping to find some agreement, some way that they could all work together …

Newkirk: But other people in the SCLC had not endorsed that plan. They didn’t like or trust the Invaders. John says that he had gone into hiding because he thought SCLC members believed he might have been working to set King up.

Burl Smith: There were actually people in SCLC—I’m not going to give any names, but they spent, oh, the next month or some saying that we were a part of the assassination, that we had set Dr. King up to getting him down to the Lorraine.

Newkirk: John didn’t trust the SCLC, either. He thought for sure that they would just hang the sanitation workers out to dry, or would force them to settle with Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb.

Burl Smith: Oh, I figured that Loeb would probably win and that the strike was probably over, because the people left in charge were not people committed to the workers.

Newkirk: In his final address, the “Mountaintop” speech, King had promised to come back to lead another march in Memphis. It was a firm commitment that his involvement in the strike wouldn’t just be a cameo or a detour, but a central piece of his growing Poor People’s Campaign. John didn’t believe the new SCLC leader, Ralph David Abernathy, or King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, would keep that promise. But then he heard the SCLC announce that they were coming back to Memphis.

Ralph David Abernathy: We will conduct our march in support of the sanitation workers here in Memphis as scheduled on Monday, April the 8th. It will be a silent march in his memory. We will resume work on his Poor People’s Campaign in Washington in the hopes that this nation and its Congress will legislate the necessary economic reforms to put an end to poverty in this nation.

Newkirk: Like always, the organizers relied on local groups and volunteers to be marshals for the march, to move people along and keep order. The marshals would be especially important this go-around, after the disaster of the last march. John says, the SCLC didn’t reach out to the Invaders for this role, but he and his friends showed up anyways.

Burl Smith: Nobody ever reached out to us and said, We would like you to do this. Be there. But because of our promise to Dr. King, we did what we promised, which was to be marshals.

Newkirk: The hope was that the shock of King’s death would push the Memphis mayor to give in quickly. But that morning, the marchers got bad news.

Art McAloon (journalist): At the center of today’s parade and last week’s tragic events: the garbage workers’ strike. They broke off negotiations at 6 o’clock this morning with no settlement in sight. The demonstration was quiet …

Newkirk: Still, even though the sanitation workers were no closer to getting a deal, the march was important. Civil-rights organizations could keep public pressure on Mayor Loeb and could use the national spotlight on Memphis after the assassination to really bring the heat. And now, the people marching weren’t just Memphians and civil-rights activists. Thousands of people flew in from around the country to take part.

Percy Sutton (public figure): I’m absolutely fascinated by the size of the crowd. I didn’t expect a crowd this large in Memphis. Are most of these people from Memphis, or have many of them come from other parts of the country?

Robert Richards (journalist): I understand, sir, that about 6,000 have come from out of town.

Sutton: I think that’s beautiful. I think it shows the feeling throughout the country of the need for unity and accomplishment. I’m very happy to see this.

Newkirk: The marchers set out. Ralph David Abernathy and Coretta Scott King led, with three of her children walking alongside her and Harry Belafonte.

Art McAloon: It’s a gray, overcast day here in Memphis, as thousands of the city’s Negroes gather to march in the interrupted sanitation men’s demonstration. At the head of the line, with Mrs. Martin Luther King, will be Reverend Ralph Abernathy, Dr. King’s successor. Between the two, there will be an empty space, symbolizing the absence of Dr. King. March officials estimate as many as 40,000 …

Newkirk: They wore sharp suits and hats and overcoats in the cold rain. They moved quietly down the street, no chants or slogans or singing. The march was supposed to be a rejection of the riots gripping over 100 cities. It was also supposed to be a repudiation of the last march in Memphis, where John’s group had played a role in the chaos. But here he was, serving as a marshal, guiding the march and keeping it together.

John Burl Smith: We did what we could to keep the march moving and orderly and that kind of thing. But—

Newkirk: So you felt like you were upholding the promise?

Burl Smith: Yes.

Newkirk: Did anybody look at you sideways for showing up?

Burl Smith: No, no. I think most people understood. And they were—I mean, the Invaders were supported very well in Memphis. Young people were, felt, very heroic in terms of the invaders.

Newkirk: Journalists followed the entire march, pulling aside people and asking them questions with somewhat obvious answers.

Reporter: Did it have any personal meaning to you?

Man: Did it have a personal feeling to me? Sure. I always have a personal feeling, because I am a Negro. It is something maybe you don’t understand by being white.

Newkirk: Watching the footage of the march, there aren’t really a whole lot of white participants. But the Black people who showed up didn’t care. This march was for them, by them.

Reporter: Were you disappointed at the fact that the turnout of the white community was relatively small? I didn’t see too many whites marching.

Woman: Today, no, not really. I wasn’t disappointed at all. Because that’s something, here in Memphis that is not a disappointment to us.

Reporter: You didn’t expect it?

Woman: I guess not.

Newkirk: The march stopped in front of the pavilion by city hall. Then the leaders got up to speak. Ralph David Abernathy was the new leader and face of the SCLC, but he wasn’t the main draw this Monday morning.

Corretta Scott King: I was impelled to come.

Newkirk: Coretta Scott King had actually been criticized for deciding to come to the march. For deciding to be in the movement, instead of publicly grieving and caring for her children.

Scott King: Three of our four children are here today, and they came because they wanted to come too. [Applause.] And I want you to know that in spite of the times that he had to be away, his family, his children knew their daddy loved them, and the time that he spent with them was well spent.

Newkirk: Coretta Scott King came to clearly repeat King’s demands. They weren’t just the civil-rights laws that had already been passed or the new housing bill that President Johnson was rushing to pass. King was calling for transformation, for real economic change for workers and the poor.

Scott King: Every man deserves a right to a job or an income so that he can pursue liberty, life, and happiness. [Applause.] Our great nation, as he often said, has the resources. But his question was: Do we have the will? [Applause.]

Newkirk: Just like Abernathy did on Palm Sunday, Coretta Scott King tied her husband’s life, death, and legacy to the celebration of Holy Week. He might not be resurrected in flesh, but her hope was that she could call on America to revive the policy he’d fought for.

Scott King: Somehow I hope in this resurrection experience, the will will be created within the hearts and minds, and the souls and spirits, of those who have the power to make these changes come about. [Applause.]

Newkirk: The march ended without any drama. Marshals like John Burl Smith guided people off the streets, and Abernathy and the King family traveled back to Atlanta to prepare for the funeral. Riots in many cities still blazed. But it all felt like one phase of grief had transitioned to another. It was time to reckon with how the assassination and the riots had changed Black America, how they had changed all of America. John was left wondering what might have been.

John Burl Smith: Had he been able to do what he was planning to do, we would be looking at a different America.

Newkirk: To John, that new America would have been achieved by bridging the gap between nonviolence and self-defense, between the old guard and the militants. Perhaps in the silent march, as Invaders walked in their military jackets beside the SCLC in their suits, he saw a glimmer of it.

Burl Smith: Black Power would have been able to show that we could work with Dr. King, we could work with nonviolence, and we could actually be nonviolent, but we were definitely not going to be submissive and passive.

Newkirk: John never got to see that America. Nobody did. The next day, the nation would lay King to rest. All the talk in the movement and in Washington was of how they would keep his dream alive, how they could still overcome. But John worried that the dream might be buried with the man.

Taquiena Boston

a 13-year-old from Washington, D.C., receives a diary from her mother for Christmas in 1967. She begins journaling about her life, and includes her observations about King’s assassination and the days that followed.

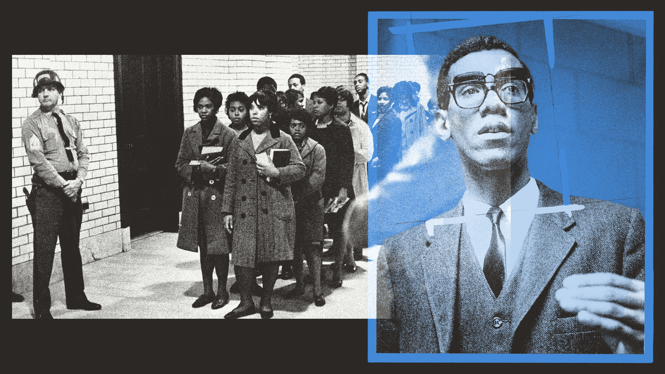

Roland Smith

a 22-year-old student at Bowie State, in Maryland, is arrested the day of King’s assassination while leading student protesters at the Maryland capitol.

John Burl Smith

One day before King’s funeral, on April 8, John Burl Smith serves as a marshal for a silent march held in King’s memory in Memphis, Tennessee.