When I was a kid, Sunday afternoons were often preempted by my mother’s dreaded pronouncement, “Let’s take a drive.” The three of us, my father driving, mom next to him, and me in the back seat, hoping we’d be home before my favorite television show started.

Hours passed with my mother enthusiastically saying, “Look at that” “Did you see that?” and each time she’d turn around to make sure I saw it, and I would dutifully look. My father never said a word, just drove through neighborhoods that all looked the same to me, but where my mother could always find something unique. We passed store windows, people walking dogs, empty lots; out into the country past billboards, pine trees, fields, cows.

It was boring. Maddening. And then…

Sometimes we were surprised by something wonderful. An animal topiary among the weeds of an abandoned house. Army parachuters jumping from a tower on a distant hill. The back of a truck flying open and its cargo of oranges rolling onto the road while the driver drove on, oblivious.

We search for inspiration; these are more like stealth attacks on our thought processes.I eventually learned the joy of being surprised by the wonderful among the mundane. Happy accidents that now as an author I appreciate, long for, and gratefully accept and use.

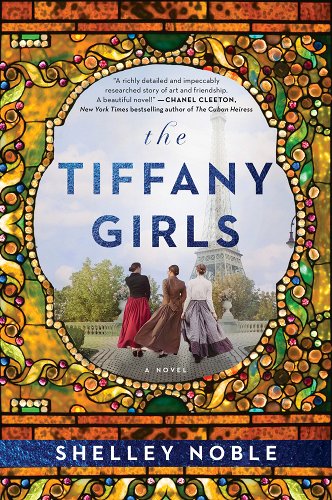

My upcoming historical novel, The Tiffany Girls, owes its existence to just such a happy accident, one that I came close to missing.

I was working on a historical mystery at the time. A Gilded Age series about a young, cash-strapped dowager countess, who in a tit for tat response to all the rich American girls invading Europe to marry titles, decides to travel to New York to make—not marry—her fortune.

I was having loads of fun with convoluted plots and characters based on dime novel characters of the period. A Secret Never Told was the fourth in the series and I decided it would center on a group of European (perhaps murderous) psychoanalysts visiting Coney Island in 1908.

I was fairly familiar with the period, had a decent knowledge of Coney Island history, but I knew nothing about early twentieth century psychoanalysis.

I began to research Freudians, Jungians, theories of the subconscious, interpretations of dreams, the use of experimental drugs, until the words and theories began to blur. But I kept after it, reading books and scrolling through site after site online. “Psychoanalytic Theories and Approaches” “Origins and Developments of Psychoanalysis” “A New Light on Tiffany, Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls.” “Psychohistorical Methods: Freud and—”

My finger frozen on the track pad, scrolled back. I didn’t even question why The Tiffany Girls were there among the early psychoanalysts. I’m a novelist; I was happy to jump down that rabbit hole just to see where it led. I clicked through.

And like Alice, I fell into a remarkable world and right into my next novel, The Tiffany Girls.

The article was a review of an exhibition of Tiffany lamps, windows, and decorative arts and the story of the women who created and constructed them. For a century these artists were largely unknown. Then in 2007, two researchers discovered two different caches of the letters of Clara Wolcott Driscoll, manager and chief creator of the women’s division of the Tiffany Glass Company. Her letters gave the world insight to the art and lives of the women who were responsible for Tiffany’s most iconic glasswork.

Why this article appeared where it did, I’ll never know. Kismet? Chance? A screw up with the SEO?

Whatever the reason, it had nothing to do with Freud or Jung. It was my next novel. Not a mystery. No murders. Just the fascinating story of the Tiffany Girls. I didn’t even question whether I could build an entire novel around an obscure group of women who made lamps.

They don’t usually come to me full blown as the basis for a novel…but they often stand in full sight just waiting to be noticed.Now two years, four hundred plus pages, and a beautiful cover later, The Tiffany Girls will be published in May. My tribute to these young women’s lives and art. And to others like them, who are yet to be discovered.

All because of a happy accident in an internet feed.

And I realized that it wasn’t the first time similar experiences had helped shape my novels. In fact, there were many, which got me to thinking about how these unexpected “accidents” propel and compel our writing. Different than inspiration; quirky, shocking, sometimes clunky, they intercede rather than inspire. We search for inspiration; these are more like stealth attacks on our thought processes. An author’s lowly equivalent of C. S Lewis’s Surprised by Joy or a Zen satori moment. A flash of “Aha” that might not lead to a mystical experience or earthshattering understanding, just a shake-up.

A number of years ago, I was in Florida and had a flat tire. I pulled into a rundown service station where they offered to plug my tire. I waited in the bare bones office with the air conditioner rattling away and a middle-aged attendant watching an ancient television showing an interview with an ex-veteran, who converted old vans and trucks into housing for homeless veterans. I spent my few minutes there, phoning my friends over the cacophony of the air conditioner and television, to say I was running late. The tire was fixed, I drove away.

Two years ago, I had just started a contemporary women’s fiction, Summer Island, about a young local journalist, whose paper has just been closed, the plight of small newspapers across the country, and a subject close to my heart. Phoebe has lost her job and her fiancé, and she and her mother decide to regroup at grandma’s New England beach house. On page 84, she walks into town and stops at the bakery to pick up her family’s favorite sticky buns, and in walks an old veteran who lives down the road and converts old trucks into homes for vets.

I had no idea where he’d sprung from. He didn’t have a character page, not even as a walk on. But there was Charley, bringing his own personality and backstory. A total surprise. And then it came to me. A chance hearing of a television interview in a Florida gas station years before—all because of a flat tire. He’d been loitering in my brain all that time, virtually forgotten, a character who would become a pivotal part of the story.

We’re surrounded by happy accidents. Things that shouldn’t be where they are; things always there but we might not have noticed; things we would never think to use in our carefully constructed plot, or overarching theme, but by their very out-of-place-ness can add a whole new dimension to our work.

I’m more accepting and thankful to them now. They don’t usually come to me full blown as the basis for a novel, like The Tiffany Girls, but they often stand in full sight just waiting to be noticed. Like potential friends, they smile at us from a window, tap us on the shoulder from behind, jump up and down in the crowd, waving their arms, trying to get our attention. They’ll even appear to us in the wrong Google feed, screaming, “Pay attention!”

And when we do… well, the rest is fiction.

______________________________

The Tiffany Girls by Shelley Noble is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.