Blanche D’Alpuget was born in 1944, the daughter of Lou d’Alpuget and Josie Stephenson, and grew up in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. She attended Sydney Church of England Girls’ Grammar School and, briefly, the University of Sydney before becoming a journalist with the Daily Mirror, rival newspaper of the Sun where her father worked.

A hyper-masculine yachtsman, champion boxer, wrestler, water polo player and, in youth, Bondi lifesaver, Lou d’Alpuget in the newsroom once shouted at cadet journalist John Pilger so ferociously for getting his facts wrong that Pilger fainted. He taught Blanche to box, surf, sail, fish, fire a rifle and execute basic unarmed combat moves, the last because he thought girls should be able to defend themselves against assault.

The journalistic gene was not fully transmitted though. “I was always aware of the fact that I was not a good journalist,” d’Alpuget says. “I had no news sense. It is a sense, and I haven’t got it. I still haven’t got it.”

Unusually, Lou recommended the works of Cambridge English literature don Arthur Quiller-Couch to Sun cadets, not an obvious choice as an influence on Australian journalistic prose. While Lou’s news sense was not transmitted to Blanche, the literary bent this suggests in him was.

D’Alpuget was on the Mirror’s full-time payroll in Sydney for just three years: life as a novelist lay ahead. First, though, there was a spell in London followed by nine years living in South-East Asia, including two periods living in Indonesia with her husband, journalist turned diplomat Tony Pratt.

‘A good guy’: meeting Hawke

In 1970, the year d’Alpuget first met Hawke, Pratt was second secretary at the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. “I showed visiting ‘firemen’ around Jakarta,” she recalls. “I was very good at that. It was one of the things expected of the wives.”

Hawke, recently anointed ACTU president, remembered seeing “this vision” for the first time, en route to the annual meeting of the International Labour Organisation in Switzerland.

“I met her first in Jakarta on my way through to Geneva when Rawdon Dalrymple was the counsellor in the embassy there,” he recalled. “I was sitting on the verandah of his house having a beer and this vision in white appeared from around the corner and I thought, my god!” For her part, d’Alpuget formed an immediately positive impression of Hawke.

I thought he was a good person for a particular reason. It goes back to Jakarta, and to showing around visiting firemen. All of them, without exception, would want to visit the Jakarta slums. And I used to take people there and […] they’d get this warm inner glow of the superiority of our culture while looking at the poor slum dwellers as if they were animals in a zoo, which I really hated.

Bob was the only person, when I asked, “Do you want to see the kampongs?” who said, “No, I don’t want to see poverty”. And I thought, ah, a good guy. And really my respect for him was based just on that.

She would see Hawke once more in Indonesia – the following year, in 1971, when he was again en route for the International Labour Organisation. As well as squiring visitors around Jakarta, d’Alpuget worked variously at the Australian Embassy, including the press office, during her time in Indonesia.

She wrote human interest pieces “with the blessing of the Australian embassy” and tacit approval of the Indonesian intelligence service, to be placed in the Australian media, smoothing the way for the first visit to Australia by an Indonesian head of state: President Suharto in 1972, in the still sensitive post-Konfrontasi period.

It was a life of “pleasure and ease … friends and parties, horse riding in the early mornings, swimming in the afternoons”, married to Tony: “We […] were boon companions.”

A ‘vivacious, unconventional’ writer

D’Alpuget returned to Australia in 1973 and lived in Canberra where Pratt worked for the Department of Defence “with consequences he had not foreseen, and he was miserable”. She felt socially restricted and stood out in a national capital then only 200,000 strong, the vast majority of whom were in the paid workforce as public servants. “I don’t much like bureaucrats and they don’t much like me,” she adds.

Her friend, feminist activist Susan Ryan, who became a Labor senator for the ACT in 1975, recalled d’Alpuget then as a “vivacious, unconventional woman in her thirties”.

Dazzlingly pretty and petite, she looked like a Thai beauty with blond curls […] Blanche was full of fun. She liked to make loud, outrageous observations about people, particularly about their sexual demeanour […] In an era of dull and careless feminist dress codes she was a welcome sight at [Women’s Electoral Lobby] meetings, a little bird of paradise in gold high-heeled sandals, tight black slacks and a mink jacket to keep out the Canberra cold, topped by perfectly ordered blond curls, her face luminous with detailed make-up.

Pratt, in turn, was an “Adonis” in Ryan’s recollection. “I loved my husband, whom I’d met when I was seventeen, and felt fiercely loyal to him,” d’Alpuget has written. “In the decade we had journeyed together we had both taken side trips, but we were mindful of each other’s feelings, and discreet.” They divorced in 1986.

It was during this period that d’Alpuget established herself as a writer.

“I was not keen on taking a job, because of our young son”; instead she wrote a novel set in Jakarta. Twenty rejection slips later, including one from publisher Richard Walsh who described it as “just a straggle of events” – he “was right, but I felt like pulling out his tongue and feeding it to the cat” – she set the novel aside. “But I had discovered the pleasures of writing and wanted to do it again.”

À lire aussi : I studied 31 Australian political biographies published in the past decade — only 4 were about women

d'Alpuget’s first biography: Sir Richard Kirby

D’Alpuget did, winning Fellowship of Australian Writers’ prizes for two short stories in 1975. Then came an unexpected, perhaps fated, opportunity to write a biography of Sir Richard Kirby, a long-serving judge and former Conciliation and Arbitration Commission president.

D’Alpuget knew Kirby’s daughter Sue from school. At the time Sue lived in Canberra and her parents occasionally visited. When Kirby and d’Alpuget met in Canberra through Sue, they found a common interest in Indonesia, especially the late Indonesian president Sukarno. “Kirby had known him personally when he was at the height of his power,” d’Alpuget later wrote, “I as an observer in the last days of his shattered dream.”

During a conversation about Sukarno’s Indonesia of the 1940s, d’Alpuget asked to see Kirby’s photographs of the period; Kirby instead sent the transcript of his National Library of Australia oral history interview. Shortly afterwards, at her father’s request, Sue sounded out d’Alpuget about whether she would be willing to help him with his memoirs.

D’Alpuget was interested but the logistics were unworkable: she had a young son and the Kirbys divided their time between Melbourne and the NSW South Coast. D’Alpuget suggested she write his biography instead. Kirby agreed. It would be published in 1977 as Mediator: A Biography of Sir Richard Kirby. During the process they became friends; Kirby nicknamed d’Alpuget “Blanco”.

D’Alpuget began work on the book without a publishing contract in hand. Getting a publisher for a serious biography was easier than for a first-time novel, however, and at Max Suich’s suggestion, d’Alpuget proposed it to Melbourne University Press publisher, Peter Ryan.

It’s very fashionable to say, oh, he’s a terrible old right-wing tyrant and so forth. And indeed, he was a martinet. But he was marvellous. He took it on on what he’d seen – the couple of chapters I wrote plus an outline.

And he really taught me how to be an author. He hand wrote me a letter every single week. First of all he gave me the style manual for the house […] When I’d do something wrong, I remember once he sent me a drawing of me having my head chopped off with a guillotine. He drew it falling into a basket with a ZUT! three times after it. But he was very, very good for a young author. They don’t do that these days.

Before d’Alpuget sent a chapter to Ryan she would send it first to her stepmother, journalist and editor Tess van Sommers. It was a production line that forged her as an author.

D’Alpuget credited both Ryan and van Sommers for turning her “into a writer”. Applying the lessons learned from writing the Kirby book, d’Alpuget did a six-week rewrite of the rejected novel and immediately found a publisher; it became the prize-winning Monkeys in the Dark.

Research on the Kirby biography included long walks along Berrara Beach, near Jervis Bay, during which Kirby gave d’Alpuget a crash course in Australian industrial law – unique in the world at that time in consisting of court-based arbitrated rulings on cases triggered by disputes between unions and employers, and the creation of court-sanctioned “awards” that embodied agreements on wages and conditions between them.

To that point, d’Alpuget’s only experience with the law had been as a teenage runaway when at her parents’ instigation police nabbed her and her much older boyfriend interstate. D’Alpuget had also done some court reporting at the Mirror. D’Alpuget was no student of biography either. “At that stage, I’m ashamed to admit, I had never read a biography,” she recalls. “I was much too busy … going to parties!”

‘Galvanised’ by 28-year-old Hawke

As the long-standing Arbitration Commission president, Kirby knew Hawke and had come to like him very much. When he first observed him, Hawke was an impatient ANU research student assisting ACTU advocate Richard Eggleston QC in the 1958 national wage case hearings.

“He couldn’t sit still,” Kirby told d’Alpuget. “You could see he was practically going mad with frustration at not being able to have a say […] From the bench we used to watch him with some curiosity and amusement.” Hawke, 28 years old at the time but looking to the bench “only twenty-two or three”, asked for an interview with Kirby in his chambers.

He came in and explained he was a research student at the ANU. He began asking me a series of questions which I found quite objectionable in tone; how did we judges make our decisions? Did we believe we had the economic training necessary for the job we were trying to do? He more or less suggested we were a lot of economic ignoramuses, and things would be better off without us. I got pretty annoyed and indicated I thought him offensive.

In the next few pages of the Kirby biography, d’Alpuget recounts the unexpectedly riveting story of Hawke’s arrival on the public stage and his role in transforming the conceptual basis of Australian wage-fixing at that time from “capacity” to “productivity”. Hawke dropped out of his ANU doctoral studies, became the ACTU’s first university-educated employee and, not yet 30 years old, was appointed ACTU advocate for the 1959 basic wage case.

The presiding judge, Alf Foster, sent word via back channels to ACTU president Albert Monk “that he thought senior counsel and not some unknown student” should present the union case. Monk stuck with Hawke whose “assault on the concepts of wage fixation was immediate, savage and effective,” d’Alpuget records.

Kirby was galvanised by Hawke’s arguments. “In the off-season I later sought discussions with economists like Nugget Coombs, Joe Isaac and Dick Downing to help me understand in some depth what Hawke was talking about,” he told d’Alpuget.

D’Alpuget herself was galvanised by Hawke the man. In March 1976 she went to Melbourne to interview him for the Kirby book.

I did not initially recognise him as the man-passing-through-town with whom, six years earlier, I’d spent an hour tete-a-tete at a party (to which I’d worn, I remembered, a new white dress my mother had made). Nor did I realise what he would do in my life: I did not know when I encountered him again that the Muse had arrived. I did not know that, old, young, black, white, as himself or masked, I would draw him or some characteristic or saying of his, in book after book.

With mutual, wordless consent it was agreed we would become lovers as soon as possible – which happened to be in a different city, the following night.

À lire aussi : What I learned from Bob Hawke: economics isn't an end itself. There has to be a social benefit

Lovers ‘as soon as possible’

The city was Canberra. Hawke was late and wearing pancake make-up. They would meet every few weeks; in between there were “no phone conversations, no notes, messages, nothing”. Hawke was rarely out of d’Alpuget’s mind. She tried never to mention his name but everything seemed to evoke his image, and all of it “shimmered with life”.

D’Alpuget’s interior world was alight: “Researching was a joy; writing was a joy; everything was a joy.” She carefully diarised their meetings. But

slowly, dreadfully, I came to realise he was having affairs with women all over the country, that his love life was a kind of freewheeling, decentralised harem, with four or five favourites and a shoe-sale queue of one-night stands.

The relationship continued nevertheless and in November 1978 Hawke told d’Alpuget about a dream in which she and “Paradiso”, his long-standing lover in Geneva, were standing on a roulette wheel. “The wheel spun, and came to rest at me,” d’Alpuget writes in On Longing. “It meant, [he] said, he must choose me: to marry.” She was, she writes, “slain with delight” but told him she would think about it and respond in the New Year.

Practical considerations arose in her mind but did not seem decisive. Some were especially telling, including the fact that he mispronounced her surname, did not know whether she had siblings and, essentially, “knew little about who I was”. She asked a psychiatrist friend to interpret Hawke’s dream: “He laughed aloud at my obtuseness. ‘It means throwing in his lot with you is a gamble’.”

More than the roulette wheel was turning, however, by the time 1979 arrived. Hawke rang daily: “I felt safe,” she says. But d’Alpuget had an emerging realisation that she knew him as little as he knew her: “We were enigmas, peeping at each other through keyholes.”

D’Alpuget began to research her second novel, Turtle Beach. It became an exercise in “unconscious autobiography”, d’Alpuget wrote later, as had the rewrite of her first novel after the Kirby biography was finished; the writing of both stories reduced the pressure of her clandestine relationship with Hawke to bearable levels, partly by channelling her and Hawke’s personae into those novels’ fictional characters.

Hawke’s attention, meanwhile, had turned to the increasingly tense question of whether he should enter parliament – this against the backdrop of disasters at the 1979 ALP conference and ACTU Congress, the death of his mother Ellie, and trouble at home in Royal Avenue, Sandringham.

His life was now awash with “out-of-control drinking”. At the back of his mind, too, was a calculation that divorce could cost Labor a few percentage points at the ballot box should he become leader. Hawke stopped calling d’Alpuget. After some weeks, in a phone conversation lasting half a minute, Hawke told her he was not getting divorced. “Each of us asked the other to leave,” Hazel Hawke wrote later in her memoirs. “We both stayed.”

From being “slain with delight” at the marriage proposal nearly a year before, d’Alpuget now first thought of killing herself, and then of killing Hawke. Each proposition was considered in practical detail over a number of days before a “shard of vanity” and the realisation that “giving my son a murderess for a mother was hardly better than a suicide, and that if I were in jail I would not see him often” terminated that line of thought.

Without revealing too many details, and certainly none of my murder plans, I told (Kirby) the story. He listened, and after a silence said, “Thank God, Blanco, that it’s over. You would have ended up sticking a knife in him.”

Is it possible that d’Alpuget really did know Hawke as little as she claims in On Longing?

No, I didn’t get to know him well at all. I really didn’t, because it was a completely sexual relationship. Brief encounters that had to be fitted in between him doing a thousand other things […] I only ever saw him behind a closed door.

D’Alpuget disavows even an appreciation of Hawke’s powerful public projection at the time “because I never saw him in public”, and in any case, “I’d been writing novels … I wasn’t all that interested.” Rather, rivals were on d’Alpuget’s mind.

In On Longing she recounts looking at a “luscious minx” on page three of the Mirror, for example, and wondering if she was another of Hawke’s “petites amies” – this while rewriting Monkeys in the Dark, whose heroine’s fascination with her lover “was mixed and corrupted with anger and tension”. She continued: “We write out our sicknesses in books, Hemingway said. Well, yes and no: Hemingway shot himself.”

A symbiotic project

At this point, in 1979, d’Alpuget was author of the critically well-received Kirby biography, had two novels in the pipeline that would be published in the next two years to acclaim, several literary prizes and foreign translations of her works but little in the way of financial reward.

She wanted to write another biography and initially chose Hawke’s mentor and predecessor Albert Monk, the ACTU’s first full-time president whose tenure overlapped substantially with Kirby’s at the Arbitration Commission. This idea fell victim to the resistance of Monk’s widow, who was disinclined to give d’Alpuget access to his papers.

D’Alpuget has said that “the Hawke book came about because of the Kirby book”, and there is a symbiotic feel to the projects, even down to their respective book launches. Nearly five years to the day after Hawke launched d’Alpuget’s Kirby biography at Canberra’s Lakeside Hotel, Kirby launched d’Alpuget’s Hawke biography at the same venue.

Melbourne Psychosocial Group members Graham Little and Angus McIntyre, and psychiatrist Michael Epstein, all attended the latter. The Kirby book required mastering the intricacies of Australia’s unique industrial relations system and d’Alpuget did so convincingly.

The language and concepts she acquired enabled her to understand Hawke’s long engagement with labour market theory and practice which dated from his research at Oxford in the mid-1950s on wage fixing under the Australian arbitration system. Interviewing Hawke for the Kirby biography brought about the fateful re-meeting of biographer and subject.

Conscious motives

What were d’Alpuget’s conscious motives for the Hawke biography? In 2014 she presented it as a simple instrumental decision after she unsuccessfully “tried and tried” to get Monk’s widow to give her access to his papers: “She turned me down … So I thought, okay, I’ll try the second president.”

Earlier, in On Longing in 2008, d’Alpuget “noted that the news media presentation of [Hawke] was mostly so simplified as to be not much more than a cartoon”. D’Alpuget

was offended that public debate relied on such spindly legs, and wanted to do something about it; I wanted to make my own presentation of [Hawke] in a biography.

Earlier again, in 1986, d’Alpuget told Jennifer Ellison that

with the Hawke biography – I just had to make some money. I mean, that wasn’t the only reason, but I had that practical reason. Nobody can expect to make money out of writing fiction, so I wanted to write a book which I thought would finance me for a couple of novels, which it has.

The interrelated fiction and financial factors behind the book were related earlier still, in 1985, to Candida Baker, “because I knew it would help make me so well-known in Australia that all future fiction writing would be easy to sell”.

D’Alpuget told Ellison another factor was that Hawke “wasn’t entirely happy” about another biography being written at the time, though she does not specify whether that concern related to the John Hurst or Robert Pullan book.

D’Alpuget also evinced genuine interest in Australia’s arbitration system; Hawke had wanted to do a doctoral thesis on it, and had spent half a lifetime working in it, while she had written a “part-history of that system” in the Kirby biography.

And there was a genuinely shared curiosity: you know, if you’ve once dreamed of going to Krakatoa and then you meet someone who has travelled there, you want to talk to him or her.

D’Alpuget told Baker that Hawke had rung her in 1978 to say that Hurst was thinking of doing a biography of him, wanting to know how much demand on his time a biographer was likely to make:

So we had a talk about it, and I said as a joke, “Well if somebody’s going to do a biography of you, why don’t you let me do it?”

This has been d’Alpuget’s most frequent response to questions about the book’s genesis. A more expansive account was given at a Canberra Times Literary Luncheon in 1982, shortly after its launch.

[I]n 1978 he got in touch with me and he said that somebody wanted to do his biography and I was the only biographer he knew and how much time was he going to have to devote to it.

So we had this conversation, you see, and it was going on and I didn’t know at that stage really but I perceived it intuitively that he’s a man who leaves a great deal unspoken and that you have to understand what he’s saying intuitively. And I thought while he was talking, that he was thinking that if you were going to be the subject of a life, he would quite like me to do it. That’s what I thought in any case.

So I said jokingly – as any shrink will tell you, there are no jokes, especially in these circumstances – I said jokingly, ‘Well if you’re going to have a biography done, why don’t you let me do it?’. And he laughed and so I laughed and that was the end of it. It was officially a joke.

In the same speech, d’Alpuget says that as early as February 1976 she had a sense of how interesting Hawke could be as a subject when a woman sitting next to her at a Canberra dinner party one Saturday night, who knew Hazel Hawke, raised Bob’s intriguing mother. The woman told d’Alpuget:

“I’ve already complained to Hazel about how aggressive Bob is,” because Hawke in those days was extraordinarily aggressive, he was like a blast of a furnace fire.

I said, “Oh yes”.

And she said, “And Hazel said, "if you think Bob is aggressive, you ought to meet his mother”.

Anyway when I heard that, I thought, there’s a story in that man, because it seemed to me that there was in that remark – that Hazel has repeated to me – an effect or, if you like, the tension between free will and determinism which I think is the tension or the dynamic of all narrative.

D’Alpuget refers to this 1976 dinner party conversation as the “seed” of the Hawke book, and the 1978 conversation with Hawke, triggered by their discussion of Hurst’s planned biography, as its “germination”. In between, in 1977, growth was driven by “that marvellous human need – that is, the need to eat”.

A 'warts and all’ biography

Little income had accrued from the Kirby book despite its critical success; Monkeys in the Dark had been rewritten and found a publisher but had not yet come out; and d’Alpuget wanted to apply for a Literature Board grant to enable her to continue writing. When her original plan to write a biography of Monk fell over, “I started thinking again about Hawke”.

So I approached him […] in late 1978, because by then it was obvious that he would have to make his move to parliament either soon or not at all. I was very conscious [of] my effrontery […] and I expected, I think, that he’d either laugh about it again or just turn me down flat, as Mrs Monk had done.

Anyway I was surprised by his reaction, which was positive and interested and, I think, despite my work with Kirby, I hadn’t realised at that stage just how flattering it is to be made the subject of a book, nor I think had Hawke realised just how traumatic it can be. We made this agreement in principle [that] assuming I could get a grant, I would start work on him in 1980.

In the interim d’Alpuget completed her second novel, Turtle Beach, which would be another critical success upon publication in 1981.

From the vantage point of late 1979, however, when after four years’ full-time writing d’Alpuget still did not have “even enough to pay the telephone bill”, she decided she would either have to make some money or return to journalism, “a fate worse than death”. She hoped and expected that a Hawke biography would be financially rewarding. It was one of the things that kept her going.

D’Alpuget got the Literature Board grant. On 3 January 1980 – her 36th birthday and just a few months after Hawke’s reneged marriage proposal drove her to suicidal, then homicidal, thoughts – the first interview for Robert J. Hawke: A Biography was conducted.

“We set up a meeting […] in Sandringham just around the corner from his house, in the house of a friend of mine,” d’Alpuget recalls. Says Hawke: “It developed rather intimately … but it didn’t affect what I had to say.”

Hawke’s agreement was conditional on it being a “warts and all” portrait, a judgment based on his belief that voters understood he was human like them. “I just reckon I know the Australian people,” he said, conflating them with Australian men. “A hell of a lot of them could recognise themselves in both my drinking and my womanising. I think they make a judgment on the full person.”

Unlike the Kirby biography, the book did not immediately find a publisher. Peter Ryan at Melbourne University Press “knocked it back straight off – said, ‘Oh no, he’s alive!’” In a letter to d’Alpuget later, Ryan reiterated his “old-hat preference for "Life” which is dead, career complete, personality finished and the surrounding events reduced to proportion by the perspective of the years". Penguin Books also rejected the proposal.

A ‘cowboy’ publisher: Morry Schwartz

D’Alpuget’s literary agent, Rose Creswell, suggested Morry Schwartz, whose innovative Melbourne publishing house Outback Press had recently folded: but not before releasing contemporary Australian classics like Kate Jennings’ Come to Me, My Melancholy Baby and A Book about Australian Women by Carol Jerrems and Virginia Fraser.

Outback Press also had some unlikely commercial successes, including the Kate Jennings-edited Mother, I’m Rooted: An anthology of Australian women poets, which sold 10,000 copies in an Australia, whose then population was less than 14 million people.

Schwartz had a colourful reputation – “the kindest thing said about him was that he was ‘a cowboy’,” says d’Alpuget – and was a long shot as a publishing bet. But the book was a long shot for Schwartz, too. There were two biographies in the marketplace already.

More serious still was Hawke’s extreme behaviour when drunk, and political embarrassments which made some conclude his ascent was over. “It was thought that he’d absolutely shot himself in the foot,” d’Alpuget recalls. Max Suich told her, for example, upon hearing about the planned biography, “Well you’d better be quick, dear, because he’ll be ‘Bob Who?’ in six months.”

She and Creswell flew to Melbourne to talk to Schwartz. The meeting took place in the street. “Morry, who was around thirty and drop-dead good-looking, conducted the interview leaning against a low, fast, navy blue–coloured car that he owned, or hired, or had borrowed,” says d’Alpuget.

One was never quite sure. He rested an elbow on the car roof and from time to time turned his Hollywood profile to snatch another black grape from the bunch he held by its stem between thumb and first finger.

Schwartz backed the book with zest, offering an advance big enough to research the book properly.

In d’Alpuget’s view he did this for two reasons:

[F]irst, he was a businessman, and sensed the book could become a best-seller if Hawke’s career flourished. Second, as a Jew, he deeply appreciated Hawke’s support for Israel at a time when doing so was literally dangerous and potentially disastrous for Hawke’s career. Of these two, I think the second reason was paramount.

In d’Alpuget’s estimation, Schwartz was also capable of publishing the book with unusual speed. “I have attacks of being politically canny,” she said later of her conviction that Malcolm Fraser would call the federal election early and that the book therefore must, to avoid irrelevancy, be out before the end of 1982.

D’Alpuget had the Literature Board grant, the agreement of her subject, a publishing contract, a healthy advance on royalties, had begun conducting interviews and was on her way to producing the book. Hawke’s memory of the process was “a hell of a lot of interviews”.

In a letter written late in the manuscript’s preparation, d’Alpuget told Peter Ryan that, “To say … working with him is a nightmare is the blandest understatement: once, in a 2-hour taping session, there were 27 telephone calls.”

On the road to the Labor leadership

Four things were happening simultaneously, in fact, in the nearly three years between the first interview in January 1980 and the book’s publication in October 1982.

Firstly, Hawke was on the road to seizing the Labor leadership, the necessary prelude to becoming prime minister. Secondly, d’Alpuget was making a political intervention to help Hawke achieve his goal. Thirdly, d’Alpuget was symbolically reclaiming Hawke as a man before, after publication, putting him aside. And fourthly, through the biographical process conducted by d’Alpuget, Hawke was settling and projecting an identity which formed the personal plank of the platform from which he pursued and conducted his prime ministership.

The first of these elements, that Hawke was bent on seizing the Labor leadership, was widely known and understood at the time, though the story behind-the-scenes – that Hawke “had more blood on him than the entire stage at the end of Hamlet” – still remains largely submerged. Hawke had been vaunted as a potential prime minister for years.

His leadership credentials were the focus even at the press conference when he announced his candidature for the seat of Wills, as Hurst and Pullan both pointed out in their biographies. “Newspaper files had grown fat on reports of his deeds and on speculation about where he was headed,” Mills notes, “[and] he was in demand by TV interviewers.”

D’Alpuget argued in her biography of Hawke that his success in using the media, at least that outside Canberra, “was so great largely because publicity – being the centre of attention – corresponded perfectly with a major element in his personality, laid in infancy and childhood”.

Beginning with his parents, Hawke “relished and had the knack of mesmerizing” his audience. D’Alpuget quotes Hawke’s personal assistant, Jean Sinclair, on the extrapolation of this to his later career. “It was cruel to watch Bob with journalists,” Sinclair told her. “They were lambs to be slaughtered.”

Canberra Press Gallery journalists proved a tougher audience than those outside the national capital, however, and parliament itself was the prism through which gallery journalists rated politicians.

As a parliamentarian and as shadow minister for industrial relations, Hawke failed to enchant gallery journalists, impress Labor colleagues, or cow conservative prime minister Malcolm Fraser. In The Hawke Ascendancy, Paul Kelly quotes from a 1981 report by Laurie Oakes, then Canberra bureau chief for the Ten Network, after Hawke guest-compered a popular daytime television program, The Mike Walsh Show.

Since Mr Hawke entered Parliament he has not done himself justice. He does not perform nearly as well in Parliament – or in Caucus by all accounts – as he did yesterday as a television compere. His media skills are unquestioned. But a politician requires other skills as well […]

Mr Fraser so far has not found Mr Hawke much more difficult to deal with than a number of other Opposition frontbenchers … There is more to politics, especially in the big league at the national level, than making like a television star.

In private, including among members of the Labor caucus, comments were frequently much the same. Labor frontbencher Senator Susan Ryan shared Oakes’ assessment of Hawke, rather than that of her friend d’Alpuget.

Blanche, characteristically, had formed an instant and immovable view: her subject should become prime minister of Australia as soon as possible. I was very far from that view. Often on a Canberra Sunday evening, a regular night off for us both, we would debate and argue Bob’s leadership potential.

She made some memorable observations about him; memorable because they turned out later to be true. When I pointed out that his contribution in the parliament and shadow Cabinet was, although perfectly workmanlike, not spectacular, she said that Bob would only flourish fully in the number one position: only leadership could provide the optimal psychological environment for him.

Some other Labor frontbenchers like Tom Uren thought Hawke “brought a charisma, a folksy, friendly, ‘good bloke’ relationship with the Australian people he had built up over the years” as ACTU president – the same point Labor frontbencher Mick Young made at greater length to biographer John Hurst, quoted by him on the opening page of Hawke, the Definitive Biography.

But at the time d’Alpuget was writing her book, that sentiment was still a minority one and did not deliver Hawke the numbers to displace Bill Hayden. Was d’Alpuget’s biography part of some Hawke master plan to seize The Lodge? Not according to d’Alpuget in March 1985, two and a half years after the book’s publication.

People ever afterwards said, “Oh isn’t Hawke clever!” It’s faintly irritating. I had to consider all these bloody things, all the time. Bob had no idea of the timing, in fact for ages it was unreal to him, and it was only right towards the end of the process, when I started showing him the manuscript to read, that it started to become real. Up until then he’d been interviewed by at least five million people, and it was just something that he did. Part of the day’s work.

Hawke himself said he had not considered writing an autobiography or organising for someone else to write his biography. “No, I hadn’t thought about it at all,” he said. “I was extraordinarily busy, couldn’t do it myself. I was just doing my job. This came along. I knew she could write.” Hawke didn’t want a hagiography.

I wasn’t regarded as a lilywhite kind of person (and) I was more than happy to stand on my record of achievement … I don’t think it did me any damage. I think on balance it probably helped. I think people made a judgment about me. On the whole they knew the foibles but they knew the pretty substantial record of achievement I had under my belt.

À lire aussi : Vale Susan Ryan, pioneer Labor feminist who showed big, difficult policy changes can, and should, be made

A biography to ‘help Hawke achieve his goal’

The second thing happening in this period was a political intervention by d’Alpuget to help Hawke achieve his goal. D’Alpuget did not declare this as her intention. Nevertheless, the Hawke biography was authorised and d’Alpuget had her subject’s cooperation.

D’Alpuget was not going to write a book that would hurt Hawke’s chance of winning the Labor leadership and thereafter the prime ministership, though upon first reading some did not grasp the sophistication of her approach.

It was a sign of Hawke’s self-confidence as well as, he would say, his confidence in the Australian people, that it had to be a “warts and all” portrayal, and d’Alpuget largely provided it. “I’d become convinced that despite all evidence to the contrary, he would somehow make it to prime minister,” d’Alpuget says.

Another aspect of her role in this was not publicly known. Hawke asked d’Alpuget to try and turn a Hayden vote for him. “Bob had told me how he was going to unseat Hayden,” d’Alpuget says. “And he’d asked my help with a particular Hayden supporter in the caucus. He’d asked my help in trying to turn this person, to vote for him.”

There was a “unique angle” according to d’Alpuget: “I was good friends with this person.” It was Susan Ryan. In the second edition of her Hawke biography, d’Alpuget would describe herself openly as a “Hawke camp insider” in the notes at the front; but not in the first edition. It was concealed even from her publisher, Morry Schwartz, at the time.

It was incredibly frustrating. Because the book came out in October, and all of this was going on October, November, December, January, February – all of this plotting and so forth.

So maybe it was sort of November, December, January. And I knew what was happening. [A]nd and I couldn’t say a word – I couldn’t say to Morry, “Morry, print some more copies!” I didn’t tell anybody.

This underlines the dual nature of the author as both biographer and political player. While those roles were congruent, d’Alpuget’s verve and high estimation of her subject underpinned artistic risks from which a lesser, more instrumentally focused, biographer in this situation would shrink.

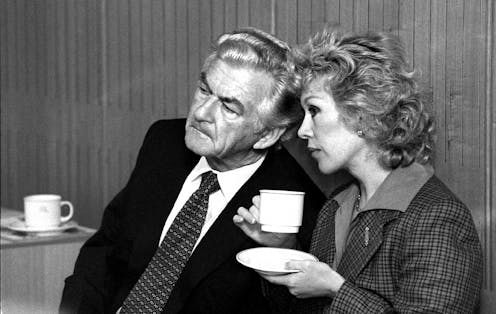

The choice of cover photograph for Robert J. Hawke is an example. “Morry Schwartz and I sat on the floor in his office in Melbourne and we went through gazillions of photographs,” d’Alpuget recalls. “And we picked that one. If you know Bob, you know he’s drunk.”

The picture, by American photographer Rick Smolan, shows Hawke, eyes heavy-lidded, head leaning sideways on a hand with a cigar clenched between two fingers, his expression poised between bored bemusement and impending explosion. Hawke’s crisp, stylish business attire is juxtaposed against his intense, glowering gaze. The cover’s drama is heightened by its stark black and white palette and the containment of Hawke’s face in a tight square at its centre.

À lire aussi : Summits old and new: what was Bob Hawke's 1983 National Economic Summit about?

Reclaiming Hawke – and putting him aside

The third thing happening during this period was d’Alpuget symbolically reclaiming Hawke as a man and then putting him aside.

The background was Hawke’s years of hard drinking, philandering and fighting with wife Hazel, from whom he had only a few months earlier tried to separate in order to marry d’Alpuget, but failing since neither would agree to be the one to walk out of the marriage.

“It was a very difficult situation for him because Hazel hated me,” d’Alpuget says, and Hazel knew about their previous relationship and assumed, correctly, that it had resumed. Moreover, Hazel Hawke was not the only hostile rival d’Alpuget had to contend with in the writing of the book. There was also Jean Sinclair and others.

[Hazel] said to me a marvellous thing once, much later. She said, ‘Blanche, you know what Bob’s like. When he’s drunk he’d fuck a goat’. […] But she talked to me, while hating me. So he had the difficulty of Hazel being against me, and also of course he was in a very long term relationship with Jean Sinclair, his private secretary. And Jean was aware of our relationship.

So he had this great difficulty – trapped – three women. Jean and I managed to get on well, well enough – we were professional about it. But it was difficult for him. So he took minimal interest in the book for those personal reasons.

D’Alpuget thanks Sinclair in the foreword to Robert J Hawke: A Biography for “spending so much time in passing messages to him from me, and in finding research material”. She describes Sinclair in the body of the book as “Hawke’s right arm” and spends a few pages sketching out her story as, like Hawke, an “exotic” ACTU employee.

Sinclair was schooled at Melbourne Girls’ Grammar School, had an economics degree from the University of Melbourne, had worked for the management consulting firm McKinsey and was a director of her family company.

Sinclair’s description to d’Alpuget of the state of the ACTU administration upon taking up her job in 1973 is vivid, and familiar to anyone familiar with the labour movement at that time: variations of this kind of administrative chaos were replicated at busy union head offices around the country.

D’Alpuget describes how Sinclair bore the workplace brunt of Hawke’s belief that “every day contained forty-eight hours and that he should be awake and occupied for all of them”, and remarks that “a good week for her was one in which she dissuaded him from committing himself to a major scheme: agreeing to write a book, for example”.

Sinclair was Hawke’s personal assistant and companion for more than twenty years, and she and d’Alpuget “disliked each other”. The extra demands on Hawke’s time would have been only one of the reasons Sinclair opposed the book given her own ongoing relationship with him.

Fighting Hazel

Hazel Hawke’s cooperation did not come without a fight. Hazel wrote a letter to the editor of The Age in November 1979 registering her “utter revulsion” at press coverage of a court case involving a prominent politician’s son. “My main argument is that any politician or public figure must be assessed on his job performance, and that whether his wife and family are glamorous and interesting or have two heads and are naughty should be irrelevant,” she wrote.

She continued that “no public figure who is good enough” needs the ego-boosting or public image softening that “nice little stories” involving their families entail, and further, that, “The electorate which makes this demand avoids its responsibility of properly assessing the worth and performance of that figure on the contribution he makes, or does not adequately make, in his particular area of public affairs.”

In the foreword to Robert J. Hawke, d’Alpuget says the only area she avoided, at Hazel’s request, was the Hawke children “whose privacy has already been invaded over many years”. It was, she wrote, “a price worth paying for her help and unflinching frankness, both in giving information and in reading the manuscript for accuracy of detail”. D’Alpuget wrote that she had been “guided by her perceptions a great deal, while exercising the responsibility to reach my own conclusions”.

Hazel in turn, in her own memoirs published after Hawke’s prime ministership was over, characterised herself as an opponent of the biography, then a reluctant starter and, ultimately, a supporter. She felt Hawke’s flaws being brought into the open ahead of his run for the prime ministership had a kind of inoculation effect, as well as relieving the pressure she personally felt over public perceptions of their marriage.

[I]n May 1980, Blanche d’Alpuget, who was writing a biography of Bob, came to our house to talk with me about the book. This was not easy for me […] I was not in favour of the biography.

Although Bob had authorised the book, it had been embarked upon without my approval even though it would clearly need to refer to myself, the children and Bob’s personal life. But now it was happening and I would cooperate.

I must say that I have since been glad the book was written. It broached areas of Bob’s life, drunkenness and marital problems, which could have been used against him later by the sensationalist press. When he entered parliamentary politics, voters had an understanding of the man they were considering for election. The biography also released me from feeling I needed to protect the marriage totally from public scrutiny.

Sue Pieters-Hawke has written that her mother was “distressed and angry” about her father’s relationship with d’Alpuget, and that wider knowledge of their relationship affected the interviews Blanche obtained from Hazel loyalists amongst the Hawke family’s closest friends.

“Intimates who knew of Blanche’s relationship with Bob closed ranks in support of Hazel,” Pieters-Hawke says.

As Marj White put it, “I said, ‘Well, my mouth’s closed. Anything that appears in that book will be absolutely mundane. I will not relate anything personal’.”

D’Alpuget had, in fact, pulled off a coup in terms of her power vis-à-vis the two other women closest to Hawke at that time. Within only a few months of Hawke ceasing contact and then breaking his offer to leave Hazel and marry d’Alpuget, she was spending hours interviewing him at a house a couple of minutes from his own in Royal Avenue, Sandringham, had his intimate amanuensis Sinclair passing messages and doing minor research for her, and had Hawke’s wife corralled into an interview against her will.

This was an act of triumphant repossession, all in the name of a greater good the other two women were hard pressed to obstruct: Hawke’s advancement.

Hawke would foreswear alcohol in the interests of his political career, while Hazel fell more deeply into its clutches. “The monster drink had gone from Bob’s life but infidelity had not,” Hazel wrote later in her memoir. “I felt extremely unsure about our future and was lonely. Now I would often drink alone, at home, with my solitary dinner, a very unwise practice.”

Sue Pieters-Hawke says her mother was “distressed and angry” about Bob and Blanche’s ongoing relationship, and “was by now capable of striking back when she, too, had been drinking”. Hazel made a number of phone calls to Morry Schwartz’s office demanding information about the book, making it clear that Hawke and d’Alpuget were lovers.

Once, after newspapers in Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra published a photograph of subject and biographer on the steps of Parliament House, Hazel phoned the Schwartz office and told the person who answered the phone, “Get that fucking bitch off the front page or I’ll blow the whistle. I’ll blow the whistle and he’ll never be prime minister.”

The intensity of Hazel Hawke’s battle against the biography is revealed in letters at the time from d’Alpuget to Peter Ryan, her old publisher and mentor at Melbourne University Press, to whom she sent “the Bird Tome” for critique prior to finalising the manuscript.

Hazel Hawke, who is a hill-billy termagant, is doing hand-springs in her efforts to prevent publication of the book. I have left out […] that she is a lush and a bully and have presented her as quite the Cecil Brunner rose. For that I get an hour & a half of telephone abuse.

At this very moment she is, no doubt, giving the Bird the rounds of the kitchen about it all. What she wants, I think, is a hagiography of herself, and pillorying of him. She hates him, & her greatest pleasure in life is to make him suffer. Were her portrait ever to be painted it would be with a log, a banjo and a vat of moonshine.

In the acknowledgements of Robert J. Hawke, d’Alpuget thanks Ryan for reading the manuscript when she had reached “exhaustion and despondency” under pressure of meeting the tight publication deadline. This perhaps explains the closing paragraph of the letter from d’Alpuget to Ryan containing her unvarnished comment on Hazel that, “She would make great copy in the Lodge. But I don’t think we can look forward to that.”

It was a brief down beat in d’Alpuget’s usually unrelenting belief that Hawke would indeed make The Lodge. She subsequently revised her view of Hazel’s capacity to perform as a prime ministerial spouse, based on actual performance.

“I was wrong,” d’Alpuget says now. “I had seen only her worst self. Once in The Lodge she rose to the challenge.” Hazel had hypnotherapy to stop smoking, moderated her drinking and conquered her shyness to become a good public speaker. Says d’Alpuget, “Hazel changed into the model prime ministerial wife.”

À lire aussi : The larrikin as leader: how Bob Hawke came to be one of the best (and luckiest) prime ministers

Hawke was ‘a fighter by nature’

In her speech at the book’s launch at Canberra’s Lakeside Hotel in October 1982, d’Alpuget describes Hawke as a “fighter” by nature who had fought with many, including her, and had fought for the book.

We had an argument at our first interview for this book and almost three years later, when he was reading the final manuscript before it went for typesetting, we were still arguing. We were arguing over adjectives and nouns and verbs and my interpretations. While the book was being written and particularly in the last few weeks, Bob has had to argue with those who thought that a mid-term career biography should not be published.

Indeed, he has fought for this book and he’s done so because he shares, I believe, my view that people should be able to make judgments not guesses about their political leaders, and that therefore the more we know about them the better. He has maintained this principle despite the fact that from the outset of my work on his biography, he knew it would be treated as a curiosity, misused, trivialised and distorted. And I must say that events have borne out that weary foreknowledge grossly.

D’Alpuget told the audience she had tried to write a frank account and that the biography was intended as “an early step in a movement for more penetrating analyses of people in Australian public life”.

It was a significant break from the usual mould of contemporary political biography, and initial reactions and calculations about it were wider of the mark the closer one got to Parliament House, Canberra. Many Canberra Press Gallery journalists assumed it would seriously damage Hawke’s standing.

So did some of Hawke’s rivals on the opposition frontbench, like fellow leadership aspirant Paul Keating. Hawke recalled a member of Labor’s NSW Right faction telling him at the time, in relation to the book, “Keating’s very, very happy, reckons that’s the end of you. With all that stuff in it, all your drinking and womanizing – that that’ll be the end of you.” Hawke replied, “Well, I think that shows how little Paul understands the electorate.”

It did prove the end of the d’Alpuget relationship, though. “I’d been burnt, when we’d broken up,” she says, recalling the breach over Hawke’s failure to honour his promise to leave Hazel and marry d’Alpuget in 1979.

Although we resumed sexual relations while I was doing the book I wasn’t going to fall in love with him. And also when you study somebody to that degree, it’s like having too much chocolate. You never want to see another chocolate again! So by the end of the research, and certainly by the end of the book, I really didn’t want to see him again. I was so sick of him. You can’t give so much energy to another human being, unless it’s your own baby.

This repossession and then relinquishing of Hawke had a satisfying symmetry. They next met three years into Hawke’s prime ministership for a newspaper profile d’Alpuget undertook for the Sydney Morning Herald. “The room was quiet and felt empty,” d’Alpuget reported, and Hawke was distant. “Hawke has defined his Prime Ministership as super-respectable,” she wrote.

He said repeatedly that physically he was on top of the world. Indeed, his skin tone and colour looked excellent. But […] my overwhelming impression was of a lack of vitality, that he was vanishing.

Two years after that Hawke rang d’Alpuget and their relationship resumed; covert meetings were organised during the latter years of his prime ministership. In December 1991 he was ousted as prime minister by Paul Keating and he resigned from parliament shortly afterwards.

The Hawke marriage ended in 1994 and Bob married d’Alpuget in 1995. They spent 24 years together until his death in 2019.

Settling and projecting an identity

Three of the four things happening simultaneously between January 1980 when d’Alpuget conducted her first interview for Robert J. Hawke, and October 1982 when it was published, have so far been canvassed.

Hawke was on the road to seizing the Labor leadership, the necessary prelude to him becoming prime minister. D’Alpuget was making a political intervention to help Hawke achieve that goal. D’Alpuget was symbolically reclaiming Hawke as a man before relinquishing him post-publication.

The fourth thing happening was that, through the biographical process conducted by d’Alpuget, Hawke settled and projected an identity which formed the personal plank of the platform from which he pursued and conducted his prime ministership.

D’Alpuget describes Robert J. Hawke as “a well-built book” with a good structure. “It’s internally strong,” she said later. “I was actually thinking of the architecture of a Congregationalist church I’d seen in South Australia when I was writing it: well-proportioned stone, four-square.”

In the process of construction, it could be argued that d’Alpuget did some rewiring of her subject, or at least enabled him to do some rewiring of himself through the biographical process, that helped stabilise his behaviour and settle his life generally, junking the self-destructive behaviour which jeopardised the achievement of his political goals.

It is not a claim that should be overstated; Hawke’s personality is highly distinctive and of robust continuity. Nor is it a proposition that can be dismissed.

Some of d’Alpuget’s impact on Hawke was straightforward and attitudinal – for example, concerning the position of women. In Robert J. Hawke, d’Alpuget describes his unreconstructedly sexist attitudes about, and behaviour towards, women, noting it did not change until Hawke in his fifties read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

D’Alpuget omits to mention that she was the one who lent Beauvoir’s book to him. The Hawke Government went on to pass landmark sex discrimination and affirmative action legislation for women through the auspices of the Minister for the Status of Women, Senator Susan Ryan.

À lire aussi : Anne Summers' new memoir and the bitter struggle over memory narratives of feminism

Earliest memories and uncomfortable truths

In other respects, though, the change in Hawke’s behaviour between 1979 when he was largely written off by political insiders because of his reckless, drunken and abusive behaviour, and the early 1980s when he gave up alcohol and (at least publicly) curtailed his obvious philandering, was dramatic.

Even if one ascribes the change entirely to his May 1980 decision to give up alcohol, the question remains, how was he able to give up drinking this time when he had failed on all previous attempts?

Upon the book’s publication, d’Alpuget described it as “an attempt on my part to wrap a narrative around an analysis of personality”.

I spend the first 76 pages of the Hawke biography on his infancy, childhood and youth. That’s really an unusually long time to devote to that sort of early conditioning but I thought it was essential to give it so much time to adequately be able to explain what comes later, and that is Hawke, the folk hero of the 1970s.

D’Alpuget went on to describe the unusual family dynamic before concluding that for Hawke, “In psychological terms, which I don’t use at all in the book, I think it was a hypercathexis of his intellect”. This was a rare intrusion of psychological jargon, which d’Alpuget kept from the biography itself. While jargon free, however, there is no mistaking the bent with which she approached the project.

In The Interpretation of Dreams Freud wrote of “the royal road to the unconscious”. In the therapeutic setting, patients undergoing psychoanalysis lie on a couch and are questioned about their earliest memories and their dreams, and encouraged to reflect and expand upon them.

For Hawke it was a trip from his home on Royal Avenue, Sandringham, to the nearby home of d’Alpuget’s psychiatrist friend Michael Epstein, where she would question him about his earliest memories and encourage him to reflect and expand upon them.

In these interviews d’Alpuget stirred up memories, unconscious and otherwise, and foreclosed resistance to them on his part when he could not or would not remember, by bringing to the biographical couch stories told to her by surviving family members. The most important was d’Alpuget’s revelation that the all-powerful Ellie Hawke had committed Bob, when he was a small child, to the teetotal path ascribed to Nazarites in the Hebrew bible, the word “nazir” having the spiritually highly charged meaning “consecrated”.

My research turned up all of this stuff that he would never have told me about, [like] his mother enrolling him as a little Nazarite. They were sworn never to drink in their lives. She was a … teetotaller. Obviously in her background there’d been drunks. At the age of 8 he was sworn that alcohol would never touch his lips.

And when I started research I went straight to the family in South Australia and turned all of this up, and I came to him and asked him about it. I started in January. He gave up grog four months after I told him [in] February […]

I tell you it was a high moment when the family in South Australia told me all this background about the drinking, because no way was Bob going to tell me that, let alone Hazel. And really they were the only two people whom I’d met up until that point who knew.

Hawke was “tremendously uncomfortable” when d’Alpuget raised it with him. Whether causal or coincidental, the fact that he successfully swore off alcohol within proximate range of d’Alpuget drawing key scenes like this from his childhood inescapably into his view is highly suggestive. Nor was it the only uncomfortable truth d’Alpuget brought to the surface.

We shared this other strange thing. My mother had wanted me to be a boy, and his mother had wanted him to be a girl. And unless you’ve had that experience of actual maternal rejection, which is completely denied – completely denied – at a very young age, you don’t really know what it’s like. But it gives a certain sympathy. There’s a certain symmetry to your lives.

He didn’t know that about me, but I knew that about him. And I’d discovered that in South Australia too – that his mother wanted him to be a girl. So, all the tension around masculinity. What do you get? Hypermasculinity. All the tension about, well, the disappointment about, not being a girl – well, therefore you’ve got to be prime minister. Over-compensation. And he must be a teetotaller. So for someone who wrote fiction, this was just all magic material, if you had any psychological insight. The rejection, the disappointment. It’s there, imprinted forever, like a dagger.

Empathy over shared problems like this, the novelist’s expert handling of rich source material, and a classic narrative arc emerging during research – the hero nailing himself to the cross of alcohol and then getting himself off in time to pursue the prize – all contributed to the satisfactions of the book from the readers’ standpoint.

“I did believe his virtues far outweighed his vices, and that he had succeeded in this enormously difficult task which was overcoming his drinking”, d’Alpuget says. “So to that extent I thought it was a book about a personal triumph. But I didn’t set out to do that. He did that. I just described what happened.”

This is an edited extract from Chris Wallace’s book Political Lives: Australian prime ministers and their biographers (UNSW Press/New South).

Chris Wallace has previously received funding from the Australian Research Council but not in relation to this book.