Elvis sang about it. Gardeners loathe it. Old-timers grew up on it. Suburban moms are afraid of it and pull it out with gloves … and foragers? They’re inconsistent about it. It’s a miracle cure, a deadly poison, a nutritious food, a pest, a gift.

It’s pokeweed!

This hotly contested, rich-historied, delicious plant is Phytolacca americana, also called poke, polk, pigeonberry, target, and scoke. In all of my foraging forays, I’m pretty sure there’s no plant that offers more food potential (while sidelined by modern fear and sheer ignorance) than this particular plant.

And that’s a real shame. Now that I understand it, I look forward to cooking and eating pokeweed every year. In this article, I want to share how to identify, understand, safely cook, and truly enjoy this seasonal gift. First, I’ll talk about how to forage for and enjoy this plant as the food it actually is. Then, after we’ve given pokeweed a moment to speak for itself, we’ll talk about the loads … and loads of conflicting information out there.

Ready for a long foraging foray? Let’s go!

Finding and Identifying Pokeweed

You may not know pokeweed by name, but if you live in its ample range, you’ll know it by sight, guaranteed. This opportunistic plant will grow in pretty much any disturbed ground or floodplain, and can be found in the sandy, well-draining soil of backyards, parking lots, forest edges, fields, fence lines, and trails. I find it springing out of my garden and growing around the barn, and most of all, growing out of areas where there’s been construction. Even the crummiest soil isn’t too poor for pokeweed — I’ve found it happily thriving in hard-packed subsoil where nothing else is trying.

If you draw a line up from Texas, through to mid-Nebraska, and then back east, you can see most of pokeweed’s native range. In our modern times, pokeweed has traveled west and settled along the western coastline as well.

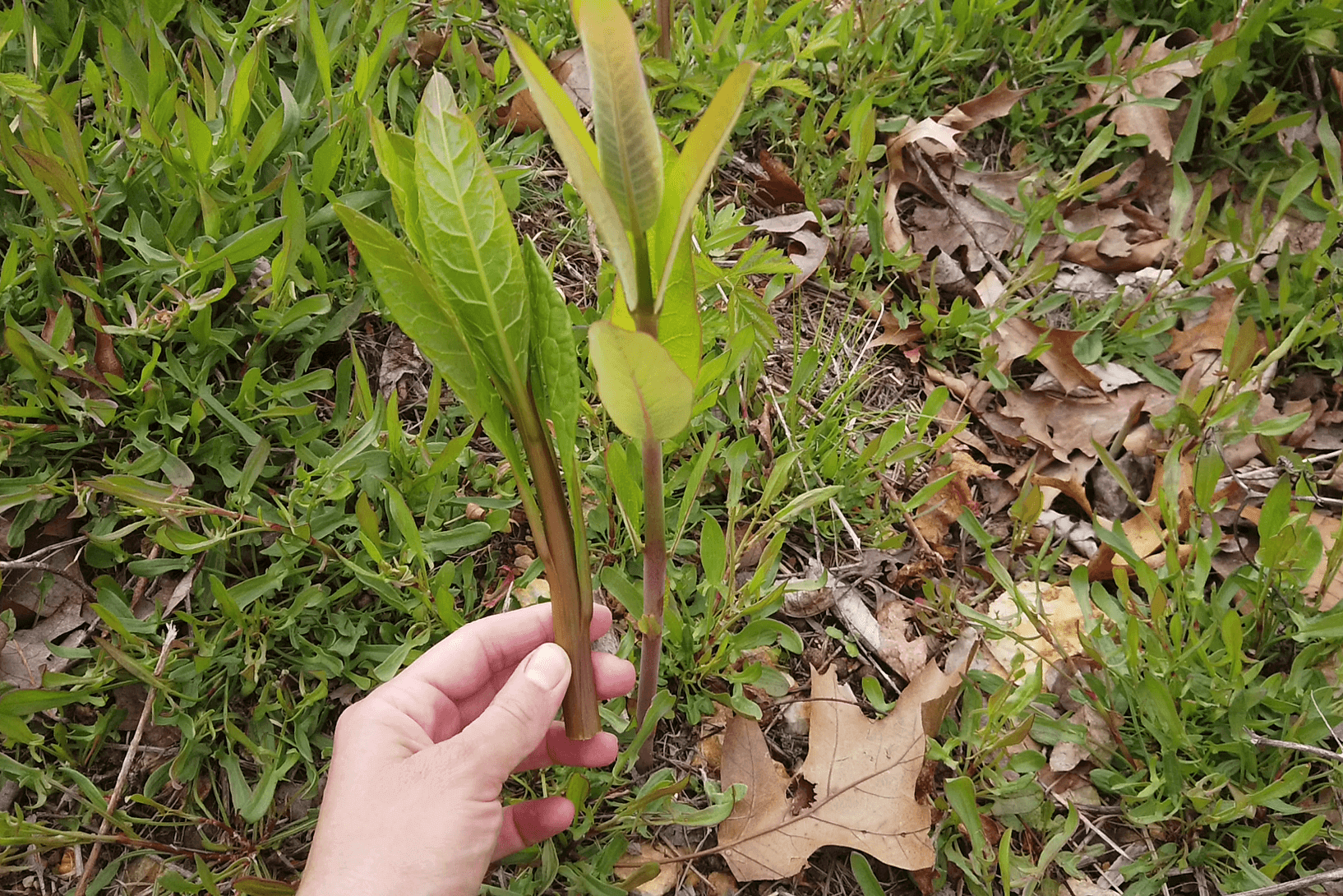

Pokeweed is a perennial native plant that grows from a massive underground root. That huge amount of stored-up energy underground gives it the ability to put out an impressive amount of quick, above-ground growth once spring is sprung. The spring shoots have two, distinctive red lines that extend down from either side of the leaf base. There are often multiple shoots coming from each root. The leaves are smooth, hairless, and simple.

Those shoots quickly transform into a tropically-huge, thick-stemmed behemoth with wide, alternate leaves and racemes of white, 5-petaled flowers. Those petite flowers soon grow into a cluster of black, shiny berries. Many plants grow more than 6 feet tall, with multiple stems clustered together. The older the plant — and they can be decades old — the more stems it will send out.

In the fall, the frost-sensitive plant will die with the onset of cold weather. The stems dry out and usually fall over throughout the course of the winter, often laying prostrate on the ground once the thaw reveals them. They’re a great way, however, to identify potential picking spots for the spring. Just follow the stems to where they still connect with their hibernating root, and watch. Once warm weather returns, green, growing life will emerge from the roots like it had always been there.

The name “pokeweed” comes from the Algonquin word “poughkone” which translates to “red dye.” The berries are the source of that distinction — and for those interested, we have an article on Insteading about how to transform the color-rich berries into a wonderful ink.

For the purposes of this article, however, it’s not the inedible berries we’re interested in, nor the poisonous root, nor the toxic mature plant. It’s the delicious spring shoots. They are the only edible part of the plant, but boy are they edible! They bear little resemblance to the full-grown monster they’ll become midsummer, but in the spring, they are a seasonal treat for anyone who knows how to collect them.

Lookalikes

Once pokeweed is in its full-grown glory, there’s really nothing else that looks like it. I mean, what other plant do you know that’s 10 feet tall, has huge leaves, otherworldly stems in a bright fuchsia-pink, and dangling clusters of jet-black, shiny berries? But as you just heard, full-grown pokeweed isn’t useable for food. The shoot is what we’re looking for, and when it’s still a mere shoot, those shaky in their identification may confuse it with some other plants.

When I was first learning how to identify pokeweed, for example (a full year before I felt confident enough to identify, harvest, and eat it), I found it easy to confuse it with dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum). Dogbane is a toxic plant that sends up a similar spring shoot at the exact same time as pokeweed, and often in the exact same habitat. Thankfully, as I learned and you will see, there are some obvious differences between the two. Once you know pokeweed well, you’ll never confuse them, so take the time to learn both plants before you progress to harvesting and eating poke greens.

The first distinction is that dogbane has opposite leaves that grow in pairs across from the other. Pokeweed has alternate leaves.

Second, dogbane produces a white, milky latex when broken. If plucked after a spring rain, the sap may dribble out of the broken stem. Pokeweed shoots break cleanly and produce no sap.

Take a look at these two plants. Can you tell the difference? Even without breaking them, you should clearly see the difference in leaf orientation. We’ve got alternate-leaved pokeweed on the left, and opposite-leaved dogbane on the right.

Harvesting

Pokeweed offers all the satisfaction of growing a domesticated food plant in terms of the sheer amount it offers, but it does so without cultivation or care. I can often collect a massive basket load of prime poke greens in under ten minutes; shattering any notion that wild foods are scanty, hard to collect, and don’t offer real nutrition. In the mid and late spring, I eat poke greens at least once or twice a week. Harvesting the shoots encourages the plant to put out more and more to compensate for the lack, and gives you about a full month’s harvesting time. As summer finally heats up, the plants start growing faster than I can pick them. When I finally let the plants grow to maturity, it’s with a fond farewell.

So that said, let’s talk about how to know when pokeweed is prime for picking. Poke shoots are safe to pick when they are meristematic — that is, when they’re immature and still growing. A meristem is the zone of a plant that is actively cell-dividing and growing. It’s young growth, tender, easy to bend, and easy to break. You see many plants putting out meristems in spring as they push out new stems and leaves. Even if “meristem” is an unfamiliar term, you’ve likely encountered them before. Asparagus is eaten as a meristem. I’d wager that many adults who have dined on asparagus regularly wouldn’t be able to identify the feathery, 7-foot adult form.

Meristematic poke has a few attributes you need to learn. First, the leaves point upward, still unfurling. Second, the leaves feel tender and are often crinkled and wavy — they’re not yet completely grown out. Third, the stem is flexible, bends easily, and snaps apart with a watery, clear-ish interior. The stems are usually green, and may have a slight blush if they are in the sun. Poke in that stage is perfect.

Poke that’s too mature to harvest looks vastly different. The leaves are large, flat, and point horizontally outward or down. The stem is rigid, and doesn’t bend easily. When broken, the stem is full of segments that aren’t translucent or watery looking. The stem has also turned a pinkish, reddish, or bright fuchsia color. Don’t harvest pokeweed at this stage.

Sometimes, if the base of a shoot is too far gone, the branch tips may still be good to pick. Tops of branches that are still tender, bend easily, and have leaves pointing up and obviously not at full size, may be perfect for harvest. Likewise, some shoots that are shade-grown may be surprisingly large, yet still tender and growing. Plants that you have previously harvested may put out a new surge of perfect shoots while unharvested plants have already matured. Basically, you’ll have to learn as you go. The plant is variable, depending on where it grows. As you increase your knowledge of poke, you’ll start developing an instinctive knack for when shoots are good or aren’t good to pick. Take the time to build up that familiarity.

With many plants, you can make multiple harvests through the spring as the underground root pushes out new growth alongside the snapped stems. Eventually, the season will probably catch up with you, and the pokeweed will start to mature too much to harvest. My general rule is that once the pokeweed starts putting out flower buds somewhere on the plant, even if there’s still a branch tip or two that’s worth picking, I stop harvesting and let it complete its lifecycle for the year. Since these are perennial plants that can last for decades, I want it to grow strong and live well through the summer and fall so that I can revisit it next spring.

Actually harvesting pokeweed is a simple endeavor. Find a suitable shoot, pull it until it snaps, and put it in a basket. Sometimes, the shoot will break off at the base where it joins with the root. When this happens, snap the pinkish root portion off until you get back to that juicy, easy-to-bend meristem again.

Here’s something else you need to know: Pokeweed is never eaten raw. It needs to be processed before it’s eaten. More on that soon.

Cooking the Pokeweed

Now, the most important thing to know about cooking poke is how to cook it properly. Pokeweed has been an important food for hundreds of years, and because of that, it’s often referred to by some rather archaic language. A dish of safely prepared pokeweed is often referred to a Poke Sallet, or poke salad. This is not the modern usage of salad, however. Sallet/salad once meant a dish of cooked greens, and that is the case with pokeweed. Pokeweed should never be consumed raw, and the traditional preparations of these tasty shoots confirms that. In every case, on three different continents, pokeweed is boiled in one or two changes of water before being consumed.

So let’s get into how to prepare my favorite spring green.

Get your biggest pot and place the pokeweed shoots you’ve plucked inside. If you ended up with any really big shoots, you can slice the stems into medallion shapes and add them to the pot as well. Now, fill the pot with water. We’re going to bring this first water to a complete boil, allow the shoots to boil for 5 to 10 minutes, then drain the water completely. You’ll see that the water from the first boiling has become an acid-green color.

Put the parboiled shoots back in the empty pot, cover with clean, cool water again, then bring it to a boil a second time. You won’t have to add as much water — the poke will have reduced significantly. Some say this second boiling is unnecessary, but others insist on at least three changes of water. I’ve found that two changes have produced a consistently good product, so this is my method.

While the pot is heating to a boil the second time, heat up a skillet and fry an onion or two with a healthy knob of butter. Once the onions are fragrant and just browned, the poke in the pot should have reached boiling. With your trusty tongs, remove the pokeweed shoots from the boiling water, drain again, and add to the sizzling skillet.

You’ll see that the poke has a very soft texture at this point (but is still a wonderfully verdant green). Unlike many other vegetables, poke stays bright colored after all this processing — yet another appetizing point in its favor.

Once the poke has been fried for a few minutes, season with salt, pepper, or optional chili flakes, and serve alongside some good whole wheat bread or brown rice with a few fried eggs. As you tuck into this decadent, truly American dish, you’ll find that poke has an agreeably gentle flavor, no trace of bitterness, and a soft texture that is hard to describe but easy to like. Some compare it to spinach, but I find that a poor comparison. Poke tastes like poke! Early on in the season, it sometimes has a mild, back-of-your-throat spiciness that is similar to Szechuan peppercorns, but most of the time, it is green, mild, and hearty. If ever the poke tastes bitter or gives you a burning mouth feeling, that either means you didn’t parboil it thoroughly enough, or you picked it too late. I’ve never experienced this distaste, however, and following the guidelines I’ve given, you shouldn’t either.

This recipe is simple. Of course, you can change up the spices, add meat, or mix pokeweed greens with other greens once they’re in the skillet, but always make sure you first boil poke in two changes of water before you progress to any other step.

Misinformation Galore!

So you’ve gotten through this whole article, and if you’ve never heard of it before, you likely think pokeweed seems like a great plant to forage, cook, and eat. Just a few parboilings, and you’re feasting like kings, right?

If you read foraging literature from the past, all authors would agree with you. Pokeweed was a poorman’s staple, a traditional food of both Native Americans and Southerners, and popular enough that it was canned commercially and sold in stores. Here in the Ozarks, the Allen Canning company was still selling it until 2000 (when they discontinued it due to tragic lack of interest).

Native Americans taught settlers how to eat the plant. It was so widely enjoyed and accepted, that pokeweed was one of the many plants sent back across the pond.

Fast forward to 1962, and you’ll read Euell Gibbons writing that pokeweed was the “best known and most widely-used wild vegetable in America.”

There was even an article in a 1979 issue of Mother Earth News that gave instructions about how to harvest Poke for Profit, collecting it for canning companies to give yourself a bit of side income.

But something happened around the 80s and 90s that suddenly transformed pokeweed from a delightful backyard bounty to a dangerous, poisonous weed. And in the decades that followed, the more modern foraging guides have been imposing unnecessarily strict harvesting rules to follow, and scarier texts concerning this plant. Many guides advise to never eat shoots that are taller than six inches, and never harvest plants that have any tinge of red on their stems. This is sometimes prohibitively conflicting information, however. Some shoots grown in direct sunlight are dangerously pink when under 6 inches tall — particularly the first shoots of the year. And plenty of shoots over 6 inches tall are green.

As you can see from my own harvesting, almost every poke shoot I pick is bigger than 6 inches. Any that had a slight red to their stems — usually the ones growing in the sun, rather than the shade — I didn’t really worry about. Any that were notably red or pink — something that coincides with being more mature and not tender — I didn’t pick. That bright pink shows maturity that you want to avoid, but I’m still not personally convinced that the slight reddish tinge on an obviously tender meristem has much of an effect after two boilings. You can make your own judgement call as you learn for yourself. Most of the poke shoots photographed for this article are from my first harvest of the year. Since there are no leaves on the trees yet, the first harvest is exposed to more sunlight, and therefore redder than later harvests in the shady late summer. I have eaten all the poke you’ve seen in this article with no problems.

I suspect that in order to offer some standard for novice foragers (as well as to avoid any liability) modern publishers have demanded a standard size and color. The problem is, pokeweed doesn’t know how to count in inches now any better than it did in the 70s when most any size of meristem was considered safe. Understanding the somewhat flexible nature of that edible meristem requires understanding pokeweed itself, and that relationship doesn’t fit in the 1 to 2 pages allowed in many foraging guides.

Online, it’s worse. Using modern sources, a shockingly small amount of actual experience, and a need for ad revenue clicks, you’ll find that the internet has turned pokeweed into a scary, toxic monster. If you want to scare yourself irrationally, search “foraging for pokeweed.” After you read through the many blogs and articles that appear, you’ll come away feeling that foraging for pokeweed is dangerous, as old-fashioned as bloodletting, and inadvisable for the wise. For all the various websites that seem to talk about pokeweed with authority, however, the truth is, many websites offer the dodgiest information I’ve found on any wild food.

Some armchair foraging sites will state, unequivocally, that the only safe pokeweed shoots are those under 6 inches … because that’s what the books say nowadays. Others reiterate that only green shoots are edible and that any with a trace of red are straight-up poisonous. Some clip fully-grown leaves from fully grown plants. Some say that poke leaves can be eaten raw in a salad because it’s called poke salad, after all. I’ve even read a write-up that claims you can eat pokeweed when it has white berries but not blackberries (the guide, unbelievably, showed unopened flower buds as the white berries).

All those statements are wrong, in varying degrees of wrongness.

As I’ve shown you, pokeweed varies incredibly. Depending on their growing environment, shoots that are well over 6 inches tall can be safe. I’ve eaten them over 15 inches tall, and I guarantee the folks harvesting poke in the 70s for professional canning companies weren’t filling bushel baskets with 6-inch shoots. Shoots that grow in the sun are redder than those that grow in the shade, and if you’re concerned, reddish shoots can easily be peeled. As far as I understand and have experienced, fully grown leaves from fully grown plants are too developed to eat safely. Poke should never be eaten raw. As mentioned, the word “salad” in poke salad has an archaic meaning. And the guy who claimed some difference based on berries was obviously wrong since he couldn’t tell the difference between a berry and a bud.

So here, again, are three sure-fire keys to know when pokeweed is safe. Remember, I write this as someone who regularly harvests, cooks, and eats pokeweed when it’s available. My claims are also backed up by Samuel Thayer’s extremely well-researched and experienced-based chapter on pokeweed in his book Incredible Wild Edibles.

Never Eat It Raw

A few documented pokeweed poisonings are directly connected to eating raw leaves — likely a misunderstanding of the old meaning of “salad” striking again. Disconnected from our traditions and ancestor’s manners of living, it’s an easy enough mistake to make. You’ll not make it yourself now, though.

Never Eat the Root or Berries

Many records of pokeweed poisonings are concerned with root and berry consumption, not the shoots. I’ve heard of medicinal uses of pokeweed root and berries, but if you don’t know what you’re doing, don’t mess around with the roots or fruit.

Only Eat Tender, Meristematic Growth

Remember the keys to identifying those quick-growing meristems:

Leaves are tender and delicate, and also slightly ruffled-looking since they haven’t fully unfurled. They point upward, rather than spreading out horizontally or pointing downward to catch the sunlight.

Stems bend, snap, and break easily, and are succulent and juicy since they’re still in the middle of their huge push of spring growth. They are green, or greenish, and never fuchsia or pink. These factors, not shoot height, are the important keys for shoot safety.

So Is Pokeweed Toxic?

Yes. Sure. Like many other foods that we regularly eat, pokeweed contains toxins when not prepared correctly or when picked too mature. That doesn’t mean poke should be written off any more than you would toxic plants like potatoes, rhubarb, or nutmeg. Both the foliage and berries of potatoes are poisonous. Only the petioles of rhubarb are edible — the big green leaves are toxic. An overdose of nutmeg is also toxic. But we understand how to use these plants, and no one would ever give you deadly warnings before consuming french fries, rhubarb pie, or eggnog. Pokeweed is maligned because of our ignorance, not its wanton deadliness.

Poke contains toxic chemicals that are not entirely understood. They are referred to as phytolacca toxin and phytolaccin, but it’s not clear if these terms refer to a specific chemical or are just used to describe the general toxins present in pokeweed. There’s also reports of alkaloids and triterpene saponins, but the fact of the matter is, there hasn’t been a huge body of research on this plant, and since it has largely fallen out of our diets, I don’t anticipate there will be a huge push to explore it anytime soon. What is known from the traditional eating preparations around the world is these poorly-understood chemicals are removed or destroyed by the boiling process.

What many of us pokeweed eaters depend on is not the dubious conclusions of incomplete scientific studies, nor the most fearful sounding click-bait blog post, but the hundreds of years tradition eating and thriving on this generous plant. Pokeweed eating is practiced on three continents, and in all traditions, it is first processed through boiling, then enjoyed with gusto. If you comb through the comments on a lot of those websites, you’ll find old-timers relating their childhood experiences with eating poke, and they often express bewilderment at the vast array of new, impractical warnings applied to their favorite wild edible.

Honestly, I’d rather trust tradition from hundreds of thousands of eaters than websites hungry for content or studies written by scientists who have probably never eaten poke in the first place. I don’t mean to be flippant about the risk involved, just realistic. The risks are largely due to ignorance and misunderstanding. If someone who didn’t know how to drive a car got in one and crashed it, I don’t think anyone would declare every car in the world to be a death trap. They would say the person in question should have learned how to drive before getting behind the wheel.

So Why Even Deal With Pokeweed?

If there’s a potential for poisoning, why even deal with pokeweed? On paper, this question sounds valid, I suppose, but in practice, it is short-sighted. I have gotten food poisoning from several restaurants — all of whom were serving food that was normal and safe. The grocery stores are lined with so-called foods that are processed and chemically-altered and packaged beyond recognition. I’ve never gotten sick from poke.

The simple fact is, pokeweed is an ample source of nutritious food that’s available in the early spring well before the garden starts truly producing. It grows rampantly, doesn’t care about soil quality, and can be harvested repeatedly. It merely requires knowledge before being consumed — something that anyone interested in self-sufficiency has the time to learn. Those who understand how to eat pokeweed understand how to live off the land just a little bit more clearly, and need a grocery store just a little bit less.