My new novel, The Queen of Tuesday, is a heightened and mythified family memoir. [1] Actually it’s a number of things. The story of my grandfather; of Lucille Ball; of an affair they enjoyed and grieved under. The affair is fictionalized, and gives the book its narratological whomp and lift. But everything else is true.

*

It wasn’t just me. We all loved my grandfather, despite everything. Isidore Strauss was his name.

That love is why I wanted to tell his story, along with Lucille’s; [2] Isidore was very obviously kind and lovable and he did hard-to-forgive things. (Maybe that makes him like any human who was ever called “kind.”)

After about thirty years of marriage he left my grandmother. She had begun drinking too much. To this day no one knows why she did.

People leave their spouses all the time. Grandfathers sometimes abandon grandmothers. The trouble was how mine left, and with whom. And in the aftermath.

*

My grandmother always craved society—friends, music, culture. But she spent the last 30 or so years of her life isolated and sad. Harriet Strauss was her name. Almost never did she go outside, and no one beyond her family came to the house. She’d hermitted herself. [3]

And even after Isidore left, Harriet’s last name remained his.

*

When Harriet would drink—which was all the time—her voice snapped with a hard edge. Sometimes she’d insult her grandkids. Sometimes she insulted me. “What do you think you’re doing there, just standing here?” There was scorn in her, a kind of lostness. And she referred to my grandfather, always, as her husband. Even after he left and took up with her best friend.

If I were to say about my grandfather: “He’s a bad man,” and write that, it wouldn’t work.Harriet asked Isidore not to divorce her, and he never did—supporting her financially even as he lived with someone else. This was viewed, in family lore, as generous. Perhaps it was. But the truth is hard to parse.

*

Isidore’s father’s life made for one of those brave immigrant stories on which a family’s self-image can float for years.

In the 1890s Jacob Strauss sailed over from Russia. He was 13. At Ellis Island no one arrived to meet him; Jacob’s older brother had failed to show. Alone Jacob wandered into the city—no money and no English—and twenty years later wandered out a rich man. Oh, how? He’d gotten a job in a hat factory; not too long afterwards he owned a rival hat factory.

Jacob found himself a prosperous builder of New York real estate, the one investment it seems impossible to lose money on. And from those investments his son Isidore—who had wanted to be a writer, but was forced to join the family business—lost his money, and ended his time flat broke.

*

Isidore had waited until his father died. And then he acted.

The official Strauss-family version is that Harriet made Isidore’s life terrible. It had become impossible to share his life with a mean drunk. And so—the day he put his father in the ground—Izzy left. And then ended up living with her best friend. Rhoda Schwartz was that friend’s name—and she became my sort of unauthorized step-grandma.

*

My grandmother—a vibrant, social woman—was forsaken for the last half of her life. She lived a forsaken life. A surly boozer who never left home. (Except for her once-a-year trip to Puerto Rico that brutalized Isidore’s bank account and confused the whole family. You can just un-hermit yourself for a week a year?)

*

In her early 70s Harriet had to go into the hospital for a broken hip; the visit thrust her into sobriety, and she remained sober for the last decade of her life. Which is to say, she returned to the woman she’d been before, the old Harriet, whom her grandchildren had never known. She was warm, engaged; she was smart. (Though she still rarely left home.) This was the late 80s or early 90s. (She lived till 2001.)

Writing this, the miles of time shorten, and I’m with my grandmother again. She’s out to dinner with my father and me. I’m early 20s—she’s early 70s. Her cheeks are gaunt; there is smoke about her; she holds a shaky cigarette. “You want the lobster, darling?” she’s asking. She, Dad, and I are by ourselves in one of those big echoey dining-rooms of the suburb where I grow up.

Her voice is a smoker’s phlegmy prattle; it clacks across the table, little splintering thrusts. “Have what you want, Darin”—extravagant with the last of my grandfather’s money. (And hers too, in a very real way.) In public, out of her house, the voice seems stranger. She is a small and frail person, breakable.

“Anyhow,” I say, “getting back to books for a moment.” I’m home from college on some break, and feeling adult, or wanting to; I tell my family about a writer named Philip Roth who they should really check out.

My grandmother looks up for a second, and the withered face withers more. The mouth falls—baffled, a small black loop.

“Mom?” my father asks. Grandma looks peacefully entranced, like a pianist whose eyes drift and dream after a long, rapt concerto.

“Mom!” My father is up and pushing aside the table, knocking water, catching the napery and spilling everything. In the shocked moment, I think of this of as overly dramatic.

When Grandma leans into me—I’m up now too—I smell the must off her, and vitamins, and clean old clothes that haven’t seen many washings and no sunlight.

She’d had a stroke—she recovered, and afterwards seemed physically if not mentally slower. We never went out to dinner again.

*

Some things here don’t add up. About the way my family tells my grandparents’ story.

It seems clear Isidore and Rhoda must have been together, romancing in secret, before he left. And why had Harriet started drinking? Had Isidore cheated before? Why did no one—not Isidore, not anyone—try to get Harriet help?

Surely AA was well known enough, and alcoholism familiar enough, for someone to have intervened earlier on her behalf?

*

It’s true Harriet didn’t want a divorce—on her deathbed she talked proudly to nurses about “her husband,” present tense, though he’d A) been dead for three years, and B) lived with another woman, Harriet’s erstwhile friend, for the last three decades of his life. This struck me, at the time, as the saddest thing I’d ever seen in person.

So, yes, she hadn’t wanted a divorce. But Isidore also benefited from not offering her one. He paid to support Harriet—keeping her in the big house they’d shared in Great Neck, long after he could afford it. But wasn’t it what a divorce settlement would’ve given her, anyway?

And of course, the other thing a divorce would’ve given her: freedom. She might have moved on. [4]

*

There were other things my grandfather did, other borderline cruelties.

Before he lost his real estate company, he could’ve asked either of his two sons—both in the same industry—to join him. He never did, wounding them both, though neither admits it. They might have been able to save the family cash we all certainly could use.

But he was kind and supportive, driving from Manhattan to the suburbs with Rhoda when I was in high school to watch me in Battle of the Bands, sitting through awful versions of songs he must have hated. (He wasn’t a “Whole Lotta Love” or “La Grange” type of guy.) He attended my graduation and my sister’s. He gave me (and discussed) books when he saw I liked writing and reading. All of it.

*

My grandmother died three years after he did, and that’s when I realized I had a lot of anger toward him and Rhoda, whom I had also loved, and who outlived them all—by many years. In a way, writing my book was my way of reclaiming the story of my grandmother, who at the least had been underappreciated by my family.

But it also is an act of love toward my grandfather.

*

In U and I (1991), Nicholson Baker examines his love of/complicated feelings toward John Updike. Rhetorically he asks whether Updike was mean, and answered himself. “Yes, he is mean.” Baker points to the short story “Wife-Wooing”: “The meanness that first bothered me, though, when I encountered it a decade ago, long before I was married, was in a short story in Pigeon Feathers.”

In that story, Updike’s narrator looks at his wife and thinks: “In the morning, to my relief, you are ugly…. The skin between your breasts is a sad yellow.” Another sentence also nags at Baker: “Seven years have worn this woman.’” Baker writes, “This hit me as inexcusably brutal when I read it. I couldn’t imagine Updike’s real, nonfictional wife reading that paragraph and not being made very unhappy.”

But there’s some admiration in Baker’s disapproval. At least part of him seems to think that Updike, in sacrificing the feelings of his family, is free to concern himself only with his art. [5]

*

My book is a novel. The man I wrote about is both my grandfather and not. I had to think of Isidore Strauss as my character, not my grandfather, and in doing so I made changes. Changes to the story, to his personality. But the truth is, I felt very close to my grandfather when writing this. A devil on the page, an angel to the reader, says Amy Hempel. We are all flawed. We like to see flaws in others.

*

An interviewer asked if I was writing this book to settle a score. No; I was writing it to tell a story.

“For a novelist, there is more to be got out of half an idea, than out of a whole one.” Saul Bellow writes in Ravelstein—meaning, I think, that any book based on an idea is too pat, or too clear on the point of goodness or badness; that kind of work seems programmatic and not real. Because, in life (and most narrative, anyway, is meant to mimic life) who the hell knows what’s wrong and right about a person?

In portraying my grandfather publicly as a selfish cheater, I felt a closeness with him of a kind I’d never felt before.If I were to say about my grandfather: “He’s a bad man,” and write that, it wouldn’t work. [6] The beauty of fiction lies not in argument, Bellow writes, but “in the unconscious self-revelation of people, in the sight of them floundering amid their own words, and performing strange strokes as they swim about, with no visible shore, in their own lives. In art you become familiar with due process.” I take that to means that you want to be a defense attorney, defending those whom readers might think of as “bad guys,” and a prosecutor against those whom a reader might think of as “good guys.”

That is, the artist should be saying to the court of reader opinion: “She’s not all bad, your honor,” or: “She seems good, your honor, but she’s also done and thought these not great things; look at Exhibit A here…”

*

In portraying my grandfather publicly as a selfish cheater, I felt a closeness with him of a kind I’d never felt before. It was now I who tucked my grandparents under the covers of their marriage bed. It was I who hid my great uncle’s fist porny mag under his childhood mattress. I got to inhabit Isidore’s head, and Harriet’s head. During the fights, the lovemaking, the breakup. I got to think of my own father as I imagined his father must have.

Isidore knew a divorce would kill Harriet, and so, for the rest of his life, he just stayed legally married to his ex. Which is why Rhoda was only sort of my step-grandmother.

*

I could write, “Art is art,” and talk about the distorting lens of fiction, and those things would be true. But it is also true that there is enough fact in my book to make me feel bad for having written it. I have plans to visit his grave the day the book comes out. [7]

All I can say, I guess, in the end is: the book is the best I have written, and I think it’s because of these complexities. And I do think Izzy, as a writer himself—or a would-be writer—would have liked it, and given his blessing.

I can’t know if that’s true. [8]

[1] I feel low. In two senses: downhearted, and scumbaggish.

[2] Some stories are intimate. They answer to private emotion. Some stories are wide-ranging. They burst their frame and throw a big shadow. Some stories, the rarest and the best stories, are both.

[3] Compare her to Lucille Ball, the proto-feminist superstar who put CBS on the map. Who was so popular that America’s reservoirs would drop when her show broke for commercial. (A national stampede to the toilet.) Who also fought to broadcast an interracial marriage. Who also invented reruns so she could have kids and keep her job. Who also was the first pregnant person ever shown on American TV. And they called Lucille our first female mogul, because she owned the most studio space in the world. And then there’s my grandmother, whose world shrunk to the vanishing point.

[4] Reading this over—and having written it—I feel not just low, but faultfinding. Who am I to judge my grandfather?

[5] This is the moral challenge to all writers. Do you feel low? Are you meant to? What does it mean if you overcome it and wrote what you want? What does it mean if you don’t?

[6] I also don’t think it would be true.

[7] I could also talk about how this book is an act of retribution for my grandmother, and all she suffered. And that’s true too, in a way. But I loved them both, and was likely closer to him, and what business is it of mine?

[8] Each of us is indeed alone.

__________________________________

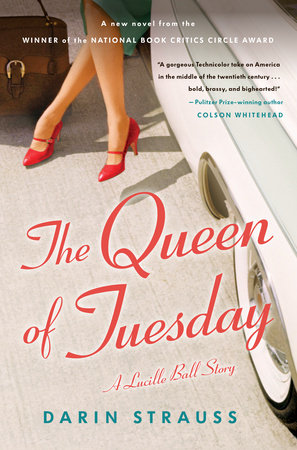

The Queen of Tuesday by Darin Strauss is available via Random House.