This article originally appeared in the September 1989 issue of SPIN.

It was a horror movie, evil descending on a New York summer that had begun with a brutal gang-rape in Central Park and a tabloid sideshow of black suspects rapping Tone Loc’s “Wild Thing” in their cell. As the Supreme Court dismantled affirmative action, quietly inflaming the center of American racial tensions, there was madness on the periphery. A black man with ties to Minister Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam clamored, “The Jews are wicked, and we can prove this”; and a young black reporter, a liberal in the employ of Reverend Sung Myung Moon’s right-wing newspaper chain, bolstered his career by circulating and multiplying the hatred he found so repugnant. Outside the posh Ziegfeld Theater on 54th Street in Manhattan, dozens of Jewish militants chanted, “We hate Public Enemy! We hate Public Enemy!” while inside, on the soundtrack to a movie some white critics called an incitement to a race riot, Public Enemy rapped, Elvis was a hero to most/But he never meant shit to me/He’s straight out racist/That sucker was simple and plain/Motherfuck him and John Wayne.

More from Spin:

- The 90 Greatest Albums of the ’90s

- 5 Albums I Can’t Live Without: Masta Ace

- Public Enemy: Our 1988 Interview With Chuck D and Flavor Flav

There were death threats and lies, a militant 27-year-old accountant whose past battle cry still hung in the air: “Louis Farrakhan [has] no right to talk, no right to walk, no right to live.” At the Slave Theater in Brooklyn, Al Sharpton rallied blacks against Jewish pressure on Public Enemy. There was a troubling symmetry: Public Enemy’s logo of a black man in a rifle sight on one side, and the JDO’s logo of a machine gun in a Star of David on the other; and the chic allure of Uzi submachine guns on both.

At the root of the frenzy there was not evil, just mundane human error: four friends from suburban Long Island, whose routine internecine squabbling, once it got away from them, had gotten way, way out of hand. A few commonplace mistakes, made by young men under great duress, had started it all.

“Did you know that the black rap group Public Enemy are anti-Semitic?”

Those were the first words you heard if you called the Jewish Defense Organization’s New York office in June. In a month of intense turmoil and confusion surrounding Public Enemy, this taped message remained one of the few constants. The status of the crew and its members has been changing day to day, but at press time, here’s how things stood: following a barrage of anti-Semitic remarks by Minister of Information Professor Griff in the Washington Times—and subsequently reprinted in the Village Voice—Public Enemy is taking an indefinite hiatus. This followed public statements that Griff would remain in the group, but be stripped of his title (June 19); that he had been fired (June 21); and that Public Enemy had disbanded (June 22). For a number of reasons, lead rapper and writer Chuck D. has refused to stand by his colleague, and refused to disown him. In the course of two weeks, Chuck D. said that Griff was his close friend of 20 years, and that they had never been friends, just professional associates, with Griff his subordinate. Criticized from all sides, and wanting—according to one of his associates and close friends—to be liked by everyone, Chuck D. made the only decision he could: no decision.

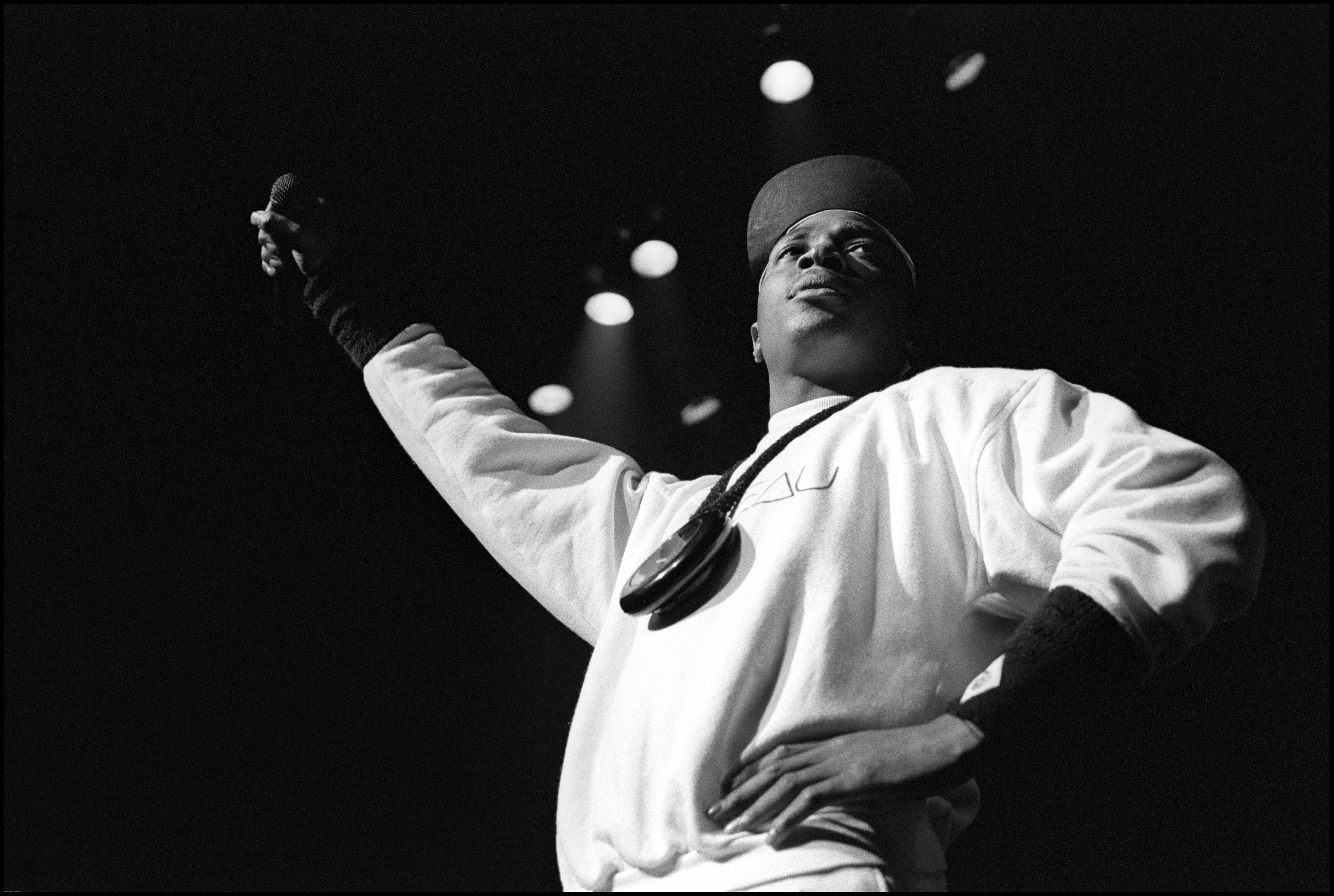

In practice, this may mean the end of the most innovative and influential group of the late Eighties. College graduates and proud adults in a genre dominated by teenagers, Public Enemy have changed the way hip hop sounds, the way it is made, what it does. “Chuck might talk 50 percent of his show—and win,” says Daddy-O of the rap band Stetsasonic. “Even if the kids don’t know they want to hear it, ’cause a lot of times they don’t know they want to hear it. And I don’t mean talk and lose, I mean talk and win. Talk and win and then go in the back. And then come back out and then win, and just leave the audience devastated and leave the venue.” The group has spoken in a dozen prisons and hundreds of schools across the country, combining activism and self-promotion in a blueprint for the next wave of black radicalism. As Bill Stephney, former vice president of Def Jam and a close adviser of the group says, in what might as well be Public Enemy’s motto, “The revolution will be marketed.”

In aesthetic terms, as a work of art, the current condition of sustained instability is the apotheosis of all Public Enemy has strived for. It is the hour of chaos extended indefinitely. But this time Chuck D. is the target of his own campaign.

Griff’s remarks capped a year of internal unrest. Last summer, in interviews with the English press, he had repeatedly hurled vicious slurs at Jews, whites and gays. He became the trade’s easiest mark: ask him a question and he would deliver great copy, some of it—not all—doctrine from Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam.

It launched a tense but interesting relationship between the group and the press. Journalists who found Griff’s remarks deeply offensive gave him a platform to offend as many people as possible, printing hateful sentiments that were not found in Public Enemy’s music, nor in Nation of Islam doctrine. It was like Lenny Bruce’s 1964 obscenity trial, where, according to Bruce, the prosecution took pleasure in saying the word “cocksucker” as they condemned Bruce for his use of it; everybody enjoyed playing with fire. The group protested that Griff’s words were taken out of context. In separate interviews, when asked to explain Griff’s statement, “If the Palestinians took up arms, went into Israel and killed all the Jews, it’d be alright,” Griff and Chuck D. each put the words into a context which removed their sting. The two contexts, however, were entirely different.

But the bile stayed largely overseas. The group closed ranks, and Griff did no more interviews. When Greg Tate cited some of Griff’s remarks in the Village Voice, Chuck D. denounced Tate as a “porch nigger.” From a New York stage, which he held like Hamburger Hill from an irate Daddy-O of Stetsasonic, Chuck D. lashed into his English critics, calling them blue bloods afraid of the intermingling of the races at Public Enemy shows. Last July, I asked Chuck D. if he backed Griff’s statements. He said that to him, “Jews are just white people, there ain’t no difference,” and seconded Griff’s homophobia. Moreover, though, he said, firmly, “I back Griff.” This became the Public Enemy line: not to let white outsiders divide and conquer them, as had happened with so many radical black organizations. Ignoring reality—as is his habit, according to a colleague—Chuck D. built a strategy and a loud rhetoric on the premise that Public Enemy was united. This was anything but the case.

Inside the group, dissent was brewing. Public Enemy’s relationship with Columbia (Def Jam’s parent label), tentative in the best of times, became more than distant. When the group’s near-platinum second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, failed to yield hit singles despite steady sales, members felt themselves victims of Columbia’s benign neglect. Some blamed Griff’s remarks for the disaffection.

There were strong outside pressures on everybody. For all his business acumen, Chuck D. had entered into a 1986 partnership by which the group received only one quarter of its royalties, a throwback to the unbalanced contracts of race music. So there was little money coming in. Even though the group’s debut album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, sold 400,000 copies, and the follow-up better than twice that, Chuck D. had to take a temporary day job at $300 a week to support himself and his wife.

Everything was new to the group members. They were elevated not just to the level of pop stars but to the level of black leaders, a status Chuck D. had courted without being prepared for it. He was also starting a family, juggling a heavy tour schedule with the demands of a pregnant wife, and after October of 1988, a daughter, Dominique. Griff separated from his own wife and moved in with his mother. At the same time, Chuck D. was trying to launch his own label and production company with Stephney and producer Hank Shocklee, the fourth player in this story. By the spring of 1989, when the interview appeared in the Washington Times, the three were negotiating seriously with MCA.

James Hank Boxley gave his first party when he was in the ninth grade. He and his friend from down the block, Richard Griffin, were the DJs. “It was about 1973 or ’74,” he says. “All I remember is everybody had the crazy big afros and platform shoes.” A tall, lanky 31-year-old dressed for Friday night in a black turtleneck and a small gold cross, Hank Shocklee—as he now calls himself—is Chuck D.’s closest friend and business associate.

As a high school student in Roosevelt, Long Island, Shocklee threw his first professional party with money his mother gave him to buy a yearbook and a class ring. “No one came to the party,” he remembers. “I had to explain to my mother what happened to the money she gave me.” After the party, Carlton Ridenhour, two years younger than Shocklee, approached him and explained why it had failed. “He said he did fliers,” Shocklee remembers, “and told me I didn’t understand the science of fliers. I didn’t want to hear about it.” Ridenhour, now Chuck D., had a marketing scheme even then.

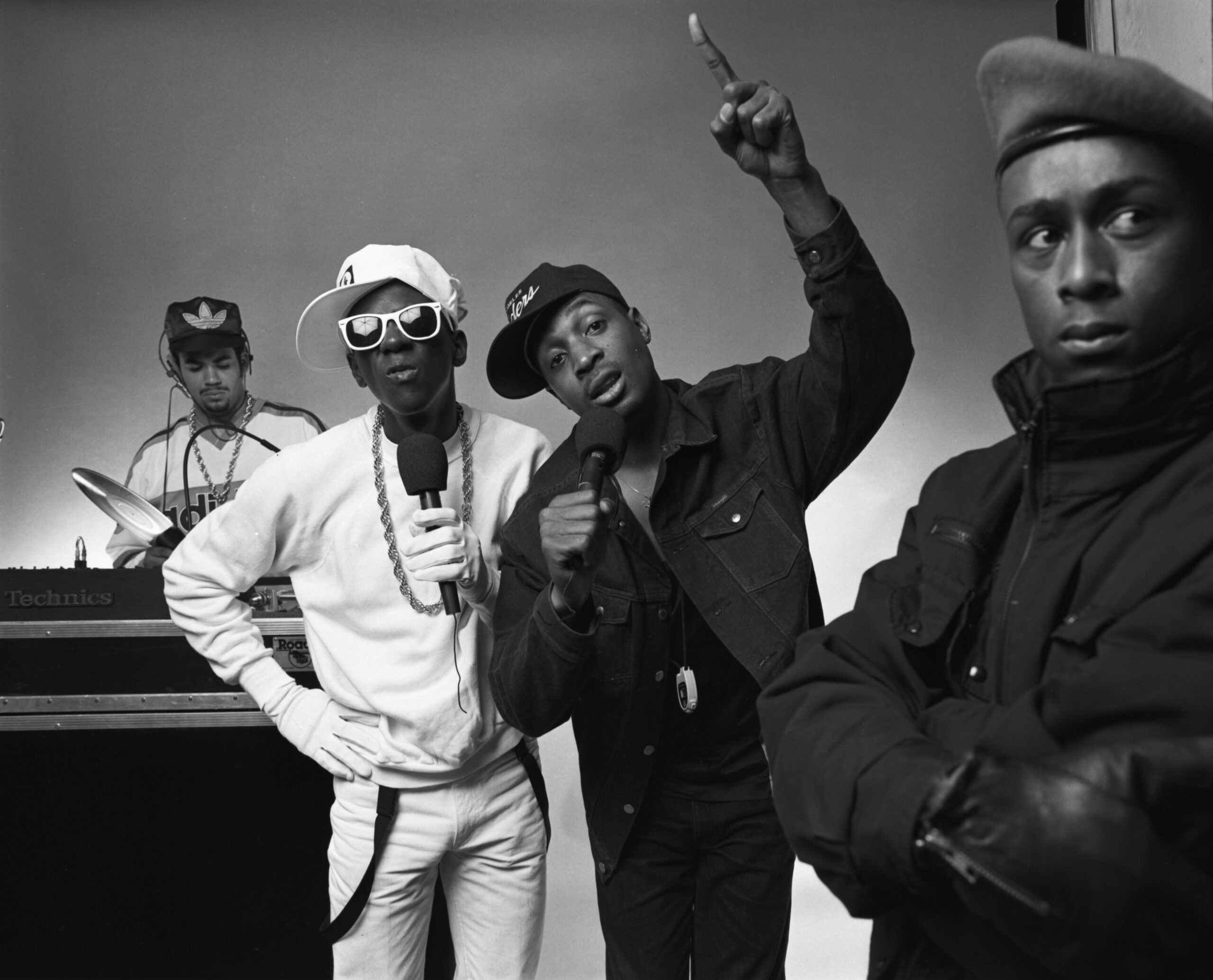

As Shocklee continued to throw parties with his brother and Griffin—now Professor Griff—Chuck D. joined as promoter and sometimes MC. His first performance was a hyped-up announcement for a party at the black Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity house at Adelphi University, where he was then an art student. They formed Spectrum City sound system, and began booking top hip hop acts from the Bronx and Manhattan. In 1979, Griff dropped out of music to form a martial arts school and Islamic study group, Unity Force, which later became the Security of the First World, or S1Ws. According to Chuck D., “Hank Shocklee was the Afrika Bambaataa of Long Island. He started it all. When we threw affairs, Griff would have guys dressed up like Black Panthers or FOI [Fruit of Islam], with the berets. And never once did we have one incident. Not because these guys would wax your ass; they earned respect and they treated people with respect. [The S1Ws] all had the same look about them. It was order.” The S1Ws also brought the requisite muscle. At one time in the mid-Eighties, there were close to 300 members.

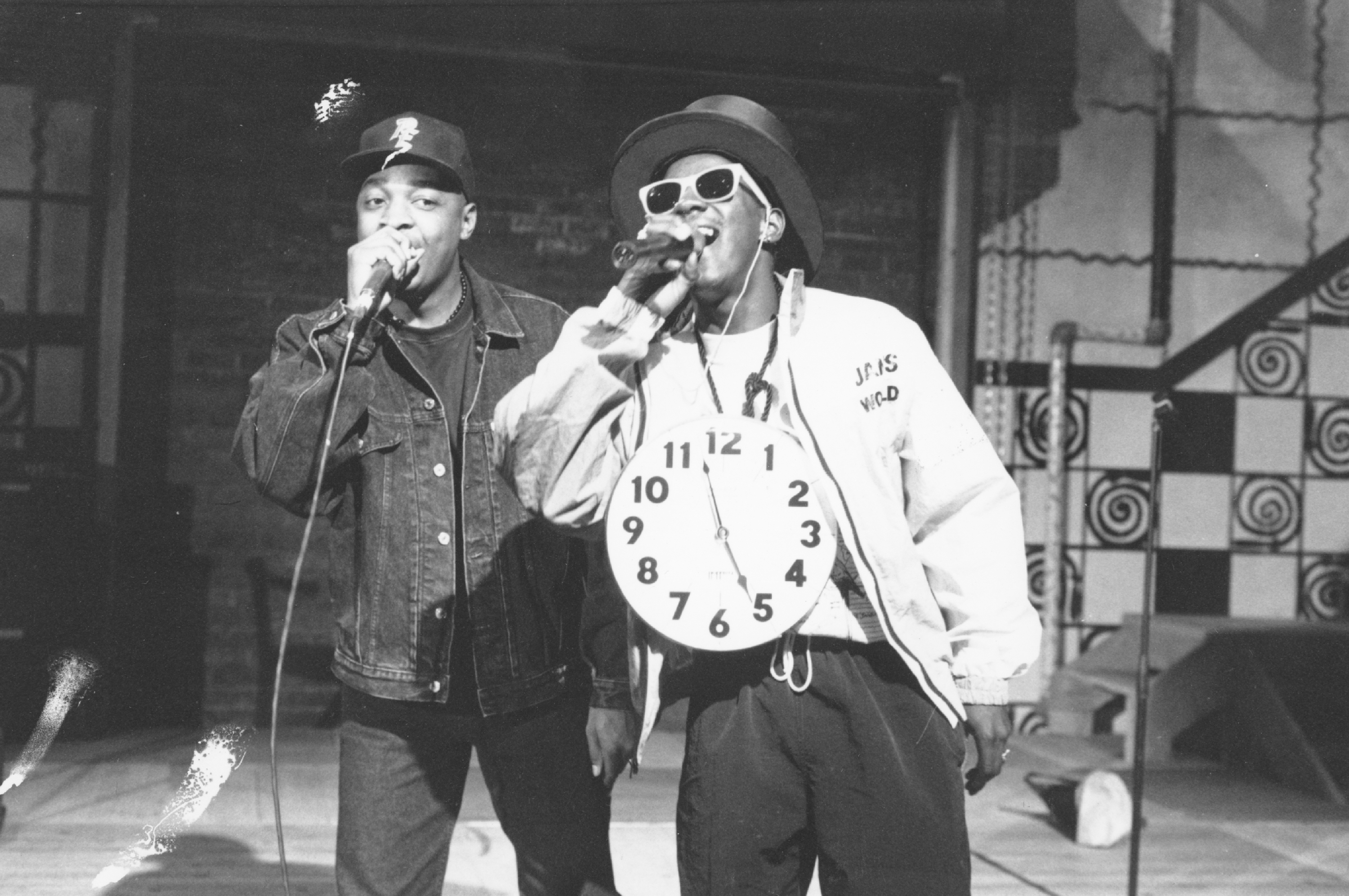

Bill Stephney, a DJ at Adelphi’s radio station, WBAU, asked to interview Shocklee (then at nearby Hofstra University) and Chuck D. on the air. “It was a pretty strange time,” says Stephney. “You had me, Chuck, Andrew Brown [now Doctor Dre of the Original Concept and a host of ‘Yo! MTV Raps’] and Harry Allen [hip hop music critic who makes a cameo on Public Enemy’s ‘Don’t Believe the Hype’] all in the same classroom. And everybody hated us.” Chuck D. joined the station and got his own three-hour show. He gave the first half of it to his most frequent and enthusiastic caller, a neighbor of Shocklee’s named William Drayton. Drayton—now Flavor Flav, Public Enemy’s second rapper—used his hour and a half to play nothing but crazy homemade tapes of himself.

“Let’s talk about something else, let’s talk about basketball,” says Chuck D., loud, always loud, over the telephone, in the middle of the crisis, a week after announcing that he had disbanded the group. “What happened to Karl Malone and Utah?” A devotee of Motown and, according to Shocklee, nothing else except rap, Chuck D. went to his first hip hop jam by accident in 1976. It was at a public park, half of which was used for the party. He played basketball in the other half. “I’m a sports motherfucker,” he says. “I used to say, ‘I don’t give a fuck about music or the goddamn party, give me the Mets, the Knicks, the Jets, and I’m straight.'” There is a boy’s club element to the friendships in Public Enemy. “Griff used to play on my team when our street played other streets,” says Shocklee. “All of us are into sports, except Bill bowls. Sports and music. We never talk about our personal lives or religion or anything. Even when the problems started, it was never anything personal, because like I said, we never got personal.”

By 1989, the relationship between Chuck D. and Griff began to change. Public Enemy was playing huge arenas, with security provided largely by beefy white off-duty policemen and -women. Griff, who neither wrote nor rapped, became less essential to the crew, and his past tirades in the press—and the risk of recurring—made him a potential liability.

The group began to pull apart. “From the start,” says Stephney, “the basic operation of the group as a business was incorrect. There simply was no real delegation of authority. Duties were not clearly defined, and communication was not clear. And the group members themselves were trying to handle the business end. It was literally anarchy. The guys didn’t talk to each other. Being on the road basically since ’87, the band became very insulated. The developed factions, different loyalties.” When Griff became road manager and got a pay raise, he and the S1Ws stopped talking to each other. The group held a meeting at which Shocklee and others talked to Griff about his ego. As the organization crumbled, Griff and Chuck D. had a basic clash of styles. Griff demanded order; Chuck D. thrived on chaos.

“Griff was supposed to be Minister of Information,” says Shocklee, “but he wasn’t allowed to do interviews. He was supposed to be the road manager, but he wasn’t allowed to manage.”

Griff was seething. Though Chuck D. declares himself, on the single “Don’t Believe the Hype,” a “follower of Farrakhan,” Griff was always much better versed in the teachings of the Nation of Islam, and resented being gagged for interviews. He felt that his role as Minister of Information was to set an agenda for the group, and Chuck D. was stifling him. Griff constantly gave Chuck D. books to read, but the rapper—more kamikaze than theorist or student—never read them; Griff saw this, according to insiders, as Chuck D. turning his back on the truth. At the same time, says Stephney, “We were all deeply aware of the severity of the comments in the English press, and the grave potential consequences of Griff talking to the press. That’s why you didn’t see any interviews for a year.”

People with outside interests in the group urged Chuck D. to fire Griff. Russell Simmons, who heads both Def Jam and Rush Artist Management (but does not manage Griff), denounced Griff as a “racist stage prop”; other Rush staff referred to Griff as poison. Griff soon abandoned his role as tour manager, furious at the lack of organization within the group.

Either on his own or with the consent of the group, Griff started doing interviews. He appeared on Barry Farber’s national radio program and on the “Evening Exchange” television show, aired on Washington’s Channel 32 on April 13. On the latter, when asked why he does not wear a lot of gold like some other rappers, Griff said, “I think that’s why they call it jewelry, because the Jews in South Africa, they run that thing.”

Then came the Washington Times interview.

It was an accident, really. Never good at keeping appointments, and habitually juggling more plans than he can handle, Chuck D. arranged to meet reporter David Mills at the cafeteria of the Comfort Inn in Washington’s Chinatown on May 9, the day of Public Enemy’s second consecutive gig at the 9:30 Club. According to Mills, the rapper had also scheduled a radio interview for the same time, and could not meet with him. Chuck D. later told RJ Smith of the Village Voice, “I refused to talk to this motherfucker…I’m not doing no fucking Washington Times interview.” (The Washington Times is a Moonie paper.) Given Chuck D.’s subsequent relationship with Mills, which was rocky but not silent, this seems like a rationalization made after the fact, when Chuck D. realized, to his embarrassment, that his radical group was falling apart because he had tried to promote it, and thus laid it open to attack, in a right-wing daily. When Chuck D. gathers a head of steam, associates admit, he sometimes makes things up as he goes along.

After Chuck D. left the cafeteria, someone directed Mills to Griff. The two talked for about 40 minutes—during which time Mills found his interviewee disarming—before Mills popped the Jewish question. “It was like pulling the lid off,” Mills says. On demand, Griff launched into the rant that became nearly all of the Times story, as previous rants had eclipsed anything else he might have said in past interviews. Among other slurs, Griff blamed Jews for “the majority of wickedness that goes on across the globe,” citing as one of his sources white supremacist Henry Ford’s The International Jew. According to Mills, even the Times‘ Jewish photographer was charmed by Griff during the interview.

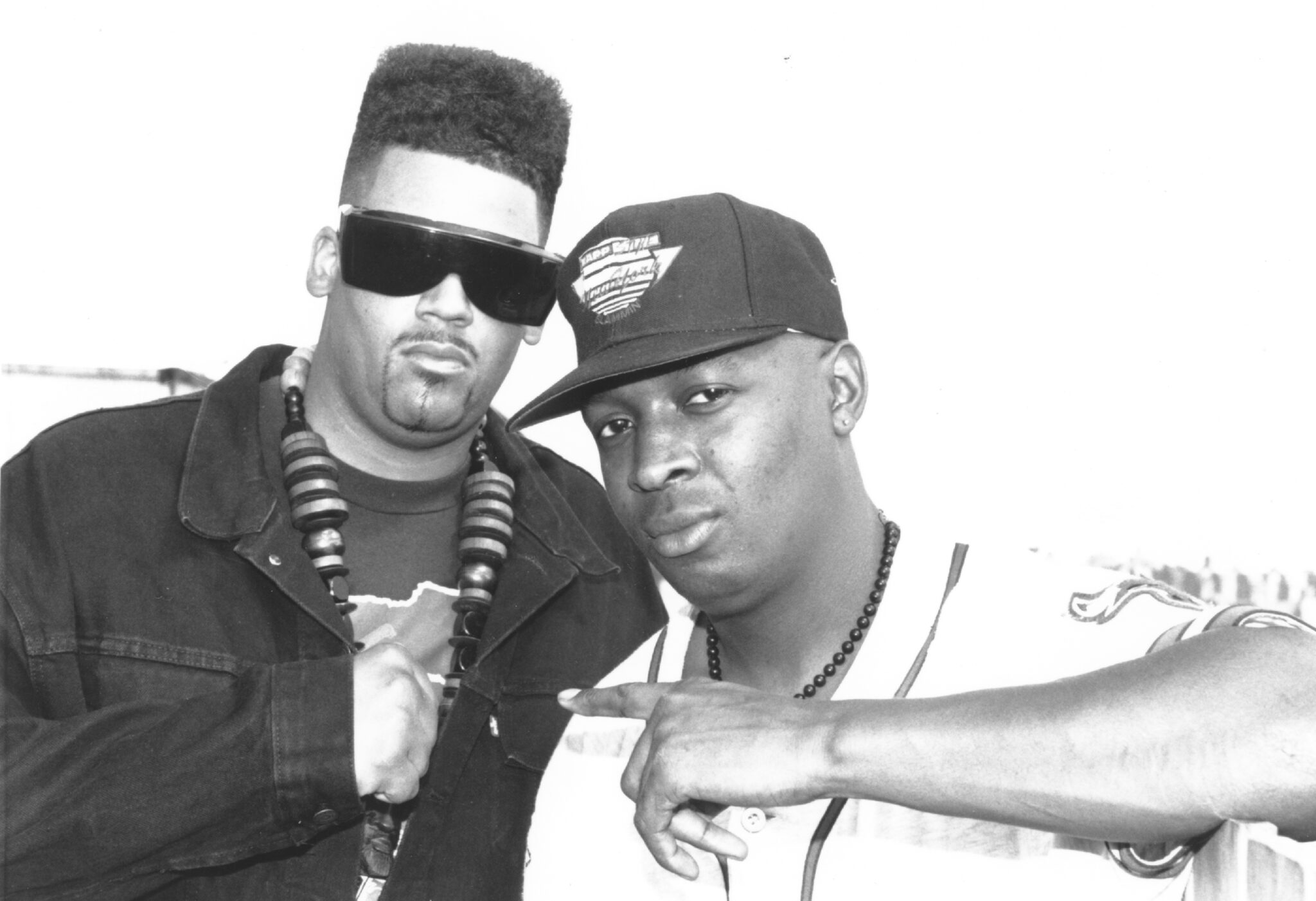

Just over five feet tall and strikingly handsome, Richard Griffin has a reputation for being exceedingly charming and polite or rude, according to his whims. For all his intensity, Griff has the sense of humor and boyish fun that Chuck D. lacks. In his Dapper Dan bootleg designer baseball jacket, with his name in big, gold capital letters across the back, he looks like anything but the ideological monster of his interviews.

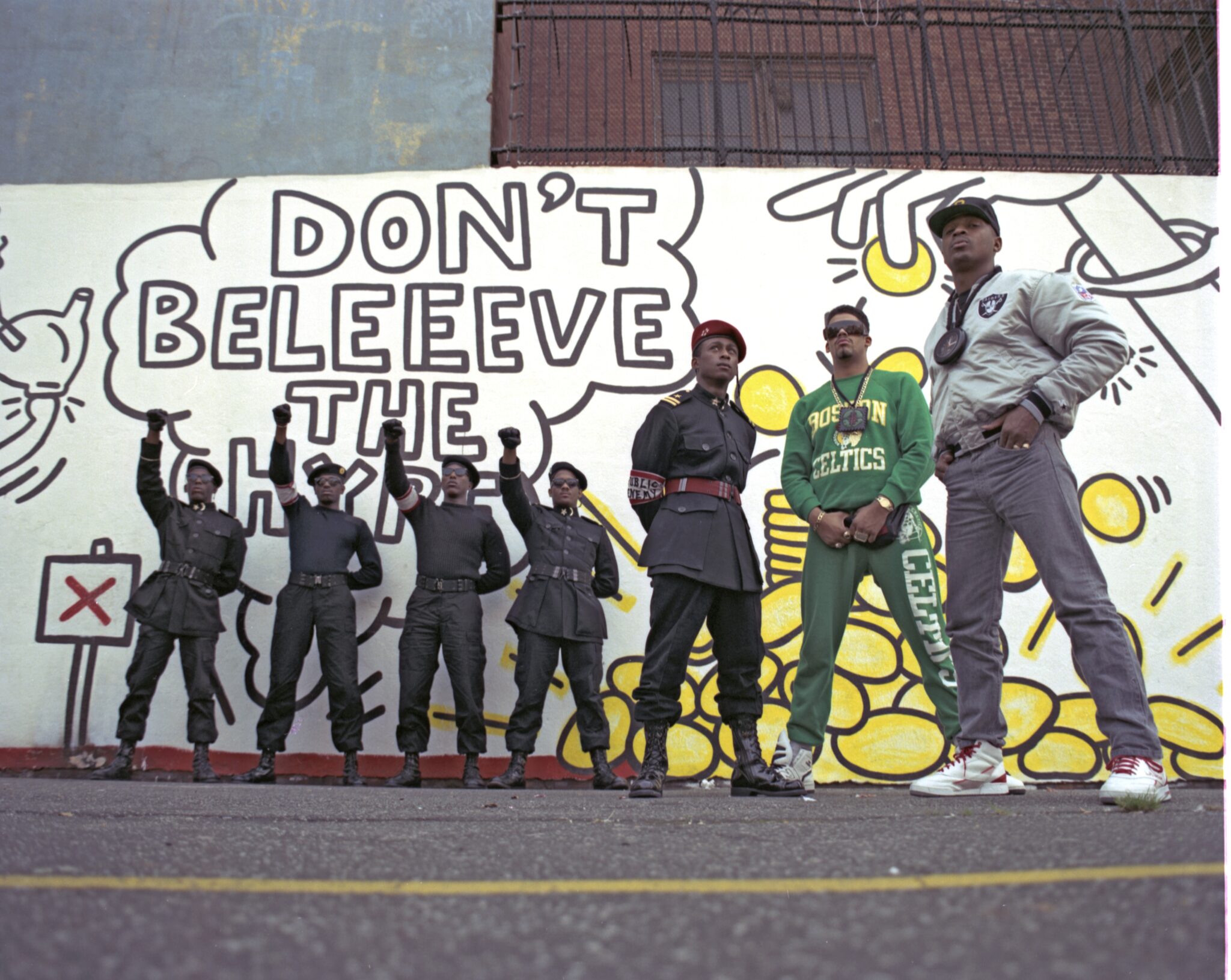

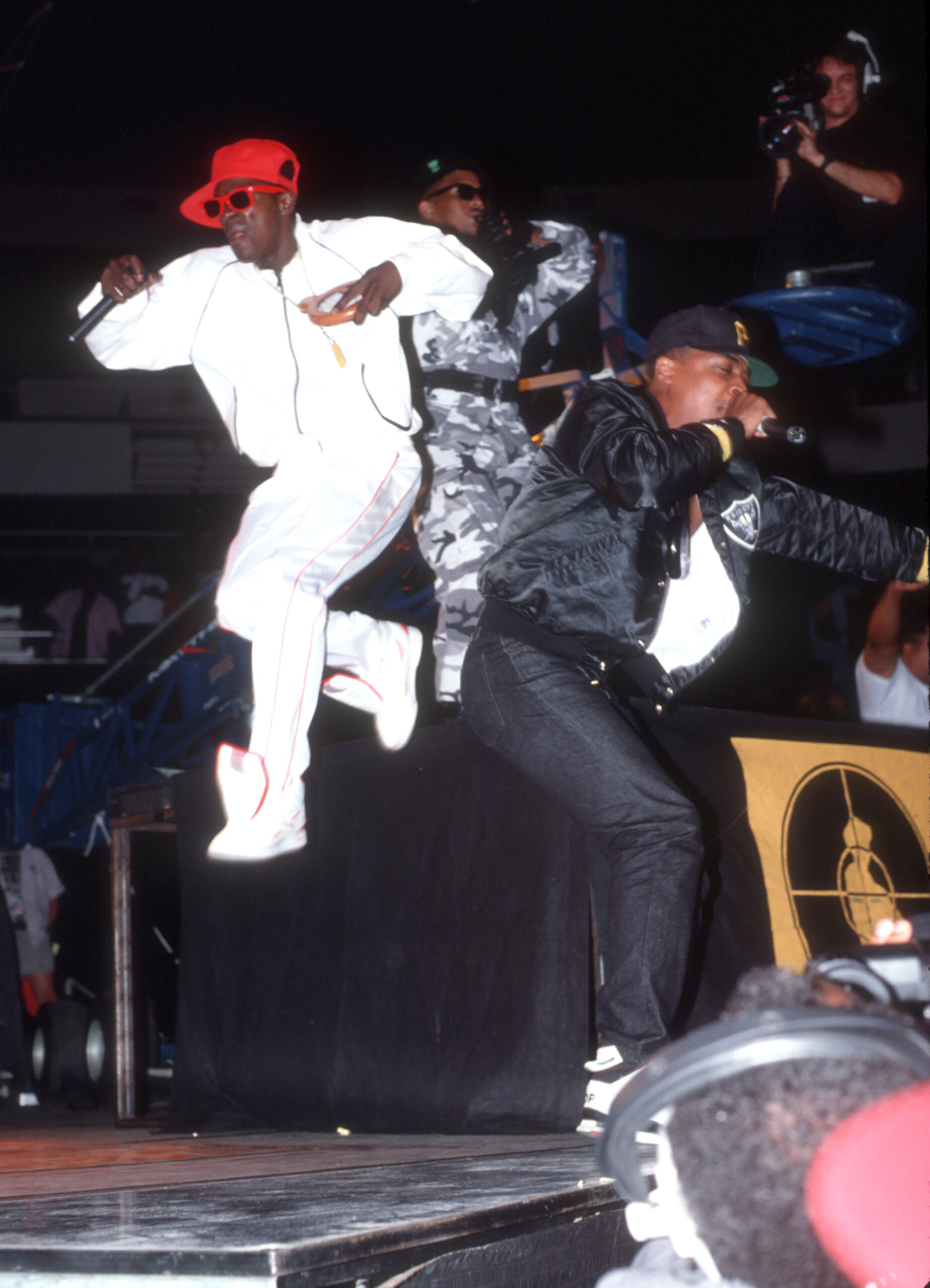

At first glance, Griff is Public Enemy’s sideshow attraction, a propagandist agitating in service of a savvy marketing strategy. He leads his uniformed S1Ws onstage in martial dance routines before the rappers, and pumps the crowd up for Chuck D. and Flavor Flav; he keeps a microphone throughout the show, while the S1Ws point plastic Uzis at the audience.

In another sense, Griff is Public Enemy. The S1Ws, as Unity Force, existed well before the group. In their berets, camouflage uniforms and combat boots, the S1Ws gave Public Enemy its identity as forcefully as Chuck D.’s lyrics or logo—a homeboy in a rifle sight, which he fashioned after getting his degree in graphic design. Rapping in an anachronistic baritone voice, Chuck D. shouted messages that, by his own admission, much of his potential audience could never understand. “When I say, ‘Farrakhan’s a prophet and I think you ought to listen’ [on ‘Bring the Noise’],” he told me, “kids don’t challenge the fact that Farrakhan’s a prophet or not. Few of them know what a prophet is.” The S1Ws, by contrast—militant black men armed with machine guns, unity and information—spoke a simple visual message that any black kid could understand. Especially in the early days, before Chuck D. developed as a performer, Griff and the S1Ws also gave the group an element of rock’n’roll theater that set it apart from other rap crews.

It is also possible, if willfully perverse, to construe Chuck D. as Griff’s mouthpiece. Chuck D. has the enormous talent, as a rapper, lyricist, marketing strategist and—perhaps most importantly, in the long run—as a young black entrepreneur. But Griff has the information, or at least some information. His job as Minister of Information, as he defined it in a November 1988 interview arranged in secret from the rest of the group, is to undertake “a re-education of black people,” drawing on the teachings of “Malcolm, Mao Zedong, the Ayatollah Khomeini, Winnie Mandela, Nelson [Mandela] and Minister Farrakhan.” According to Chuck D., “Flavor is what America would like to see in a black man—sad to say, but true. Griff is very much what America would not like to see. And there’s no acting here: sometimes I can’t put Flavor and Griff in the same room.” Chuck D. described his own role to me as “an interpreter and dispatcher” of information, and called the enticing side of Public Enemy—the hyper-inventive music and wordplay—bait for the ideological hook.

Griff and Chuck D. disagreed on whose ideology was the hook. “I build people’s identities one at a time,” says Chuck D. “That’s how we keep the group developing. First it was Flavor. I put a long time into his character. Then it was Terminator X. Third was Griff. On the second album, I gave him the title Minister of Information. I brought him out last year in Europe, gave him his first interviews. I knew it was gonna be some fire, but I stood by him every inch of the way. People always ask what that means, Minister of Information. He had to be something. Like Flavor’s the Cold Lamper. In the next year, I was gonna bring out each of the S1Ws, give them each their own identity.”

In the 13 days between the Washington Times interview and the May 22 issue in which it ran, Shocklee urged Chuck D. to talk to Mills and get him to reshape the story, but Chuck D. declined.

On May 26, Mills faxed his story to Rolling Stone and SPIN, and the Washington Times publicist sent it around the country. The Unification Church reprinted the story on the front page of its May 29 New York paper. Chuck D. handled this problem as he had the others—shortsightedly. He harangued Mills at length over the phone (Chuck D. may be, as he says, “louder than a bomb,” but as anyone who knows him will attest, he is nowhere near as succinct); when he learned that Mills was preparing a follow-up story for SPIN, Chuck D. told him, “I told Leland he better not take it.” Chuck D. denies saying this; Mills has it on tape. (In fact, Chuck D. and I never discussed the assignment.) After the Voice reprinted a large excerpt from Mills’s interview on June 14, Chuck D. called writer RJ Smith, berating him, “Any shit that comes down on me, it’s gonna come down on you. And that’s a goddamn threat…I ain’t gonna write no goddamn whiteboy liberal letter to the editor, no article either.” (He was, it appears, going to attack Smith in song, as he had earlier written “Bring the Noise,” he says, about me.)

The actual circumstances of the interview play out Public Enemy’s problems in microcosm. Having gotten himself into a situation he could not handle (scheduling himself for two simultaneous interviews), Chuck D. tried to lie and bully his way out of the ensuing problems, rather than confront them, and ended up just throwing fuel on the fire.

These threatening phone calls were ineffectual machismo, and a gross miscalculation of the forces that had been stirred up. Before the Voice piece ran, Chuck D. told Smith, “The shit storm hasn’t even begun yet.” After June 14, when the story was no longer confined to a small right-wing paper, the storm began in earnest. Griff had all but dared Jews to send “their faggot little hit men” against him; it was the sort of challenge that rarely goes unanswered.

Mordachai Levy, born Mark, has the look and voice of a nerdy kid grown into a nerdy 27-year-old. An accountant by trade, in 1981 he was arrested in connection with a bombing near the Soviet mission in Los Angeles, and again for allegedly attacking reputed Nazi war criminal Boleslavs Makovskis. He paid a fine for the second incident, but never served time for either.

The following year, at the age of 20, he formed the Jewish Defense Organization. At the time, Rabbi Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League, which had been strong in the late Sixties, was beginning to deteriorate. Levy’s slogan is “Every Jew a .22.” A better slogan, he said, “is ‘Every Jew an M-1,’ but it doesn’t rhyme.” The organization’s logo is a machine gun inside a Star of David. He formed the JDO, he says, “to help Jews fight against their enemies in the United States: anti-Semites, Nazis, the Ku Klux Klan, the Communists. Lyndon LaRouche and Louis Farrakhan have no right to talk, no right to walk, no right to live.”

At JDO meetings, Levy provides rifle and shotgun license applications, and also offers courses in weapons training. These courses, given on occasional Sundays, include practice with Uzi submachine guns. At a meeting attended by a reporter from Present Tense magazine, a young woman spoke up that “All blacks despise Jews.” Since Farrakhan said—in a remark widely quoted and routinely taken out of context—”Hitler was a great man,” he has been a target of JDO oratory. (He actually said, “Hitler was a great man, but wicked,” meaning only that he was powerful; Farrakhan devotes more energy to excoriating Christians, particularly black Christians, than he does to Jews.)

When Griff’s remarks appeared in the Voice on June 14, complete with references to the Nation of Islam, Levy responded with an organized campaign to persuade retailers and distributors to boycott Public Enemy products. Mailing out photocopies of the Voice piece to 200 record stories, the JDO included leaflets reading, in part, “If you’re white, if you’re Jewish, if you’re a decent American, or if you’re black and against Farrakhan, PUBLIC ENEMY IS YOUR ENEMY…We are organizing a boycott of Public Enemy and their materials. WE HAVE TO STOP THESE BIGOTS AND ANTI-SEMITES ANY WAY WE CAN!” According to one store owner, who called me and said he readily supported the boycott, JDO members forcefully told more reluctant retailers that “it would be a good idea” not to carry Public Enemy records. The number he left turned out to be a non-working number—one of many bogus calls.

Demonstrators chanted “We hate Public Enemy! We hate Public Enemy!” outside the opening of Spike Lee‘s “Do the Right Thing,” for which the group’s new single, “Fight the Power,” provided the soundtrack. (Lee directed PE’s “Fight the Power” video, which features a surprise cameo by Tawana Brawley. In perfect synch with the group’s deliberate blurring of the lines between news, entertainment and propaganda, Brawley appears in the video as a happy celebrity, crowned by her weeks in the news.) Public Enemy sat out the premiere, feeling helpless against the disruption they had caused Lee. As “Fight the Power” promised to become both the best-selling 12-inch in the history of Motown and one of the most controversial, Chuck D. also felt disappointed. “I was looking forward to spending the summer talking about Elvis Presley and John Wayne.”

Russell Simmons started receiving threatening phone calls at home, anonymous callers saying, “We know where you live,” or “We know where your parents live.” Persons claiming to be Simmons and a Musician magazine reporter called SPIN to harangue Senior Editor Joe Levy (no relation) about Public Enemy; both pressed Levy on why Jews, himself included, lacked the courage to stand up to Public Enemy. The Simmons caller announced Public Enemy’s dissolution and cited pressure from Columbia as the cause. He also said, prematurely, that the MCA deal was off, and cited an alleged videotape of Public Enemy onstage with Farrakhan at a Madison Square Garden rally, on which Farrakhan said, “Jews, you’re going to the ovens.”

“You can’t argue with a videotape of that,” the caller said, “and 40,000 people applauding.” Farrakhan never made these remarks.

The real Russell Simmons, who blames Griff for the phony call—probably incorrectly—told me that Columbia never put any pressure on the group, either to fire Griff or disband. “The only one putting pressure on them was me,” he said. Stephney confirmed that, far from pressuring the group, Columbia kept its distance, apparently content to let this very successful act fall apart or solve the problem or go into hiding on its own, as long as the company did not have to get involved. (Walter Yetnikoff, CEO and president of CBS Records Inc., and a Zionist, found himself in a sticky position. Recently embarrassed before his new Sony employers by a New York Times article about CBS’s slipping status in the industry, Yetnikoff saw one of his more successful and promising acts publicly calling Israel the evil empire.)

Stores began calling Def Jam and Rush Artist Management, saying they would never carry another Public Enemy item; these calls, it later turned out, were not really from stores at all, but from imposters hoping to undermine the group. Sixty JDO members with baseball bats reportedly stormed Elizabeth Street in search of the Rush office, but now this seems like more disinformation.

In Washington, David Mills was flooded with mail from anti-Semitic organizations, supporting Griff and chastising Mills for his apparent solidarity with the Jews.

Both of Public Enemy’s publicists, irked more by Chuck D.’s obstinacy than by Griff’s anti-Semitism, refused ever to work with the group again, but both continued to do just that. A Jewish independent publicist, approached by the group in a typically heavy-handed stratagem, declined to represent what she called “DJ Jewhaters.” Mordachai Levy announced on a nationally syndicated radio talk show that Public Enemy had disbanded as a result of pressures brought following meetings he had initiated between himself and high-level record company executives.

One of the quiet ironies inflaming the situation was that Public Enemy had always drawn more support from the white media than the black media. From the start, college radio stations, rock’n’roll magazines and MTV embraced the group while black radio, magazines and Black Entertainment Television kept their distance. So to the extent that the group’s name meant anything, once the trouble started, they were already in the enemy’s court. Accusations flew everywhere. By late June, it was impossible to tell whom or what to believe.

The group kept changing its story daily. On Monday, June 19th, Chuck D. told Mills that Griff would remain in Public Enemy, but no longer as Minister of Information or leader of the S1Ws. Two days later, at a press conference at the Sheraton Centre in Manhattan, Chuck D. announced to a small battery of reporters (and anxious MCA and Columbia publicists) that Griff had been fired. Wearing a black baseball hat that he refused to tilt back for the cameras, Chuck D. was uncharacteristically ill at ease, trying to appear humble without looking like he was swallowing something bad. “Offensive remarks by my brother Professor Griff over the past year are not in line with Public Enemy’s program at all,” he said. “We’re not anti-Jewish, we are not anti-anybody. We are pro-black, pro-black culture and pro-human race, and that’s been said before many times. Professor Griff’s responsibility as Minister of Information for Public Enemy was to faithfully transmit those values to everybody. In practice, he sabotaged those values.” All of this, at least in its official version, came as news to both Flavor Flav and Griff, who did not know about the firing until Chuck D. made it public. His most moving comment, lost in the commotion, was that when the press conference was over, he would have to explain his action to the black community. As Stephney tried to close the very brief question-and-answer session, Armond White of the black advocacy weekly, The City Sun, asked Chuck D. if he wasn’t just knuckling under to outside pressure.

Immediately after the conference, in a private room, Chuck D. flew into a rage. He had feared this reaction from black America all along. Under duress like few of us ever experience, he had just fired his friend, in a manner he must have known to be cowardly, for reasons that no one would ever accept. He had done the right thing, or at least a justifiable thing. But he did it too late: a year too late to persuade any but the most generous observers that he was firing Griff for moral reasons, out of umbrage at Griff’s anti-Semitism. He had made no public apologies when the remarks appeared overseas, on a small local TV station, or in a Moonie paper; now that they were on MTV, he was offended. He also ignored his own responsibility in the matter: knowing that, given an opportunity, Griff was likely to attack Jews, Chuck D. gave Griff that opportunity. In his coverage of the conference, White called the dismissal of Professor Griff—as an alternative to addressing the real and thorny issue of historical tension between blacks and Jews—”the most terrible example of sellout I have witnessed in my lifetime.” White called Carlton Ridenhour “another bought, whipped slave.”

It was the worst of scenarios. People Chuck D. did not care about except professionally considered him an anti-Semite for remarks he did not make; it was a charge he would never escape. People he cared about, politically and abstractly, considered him a sellout, maybe a whipped slave. His childhood friend probably considered him a coward and an asshole, a traitor to the truth. And other close friends, as well as close business associates, knew that he had opportunities to defuse the problem altogether, but had either added to it or avoided it.

In private, after the press conference, he disbanded Public Enemy. He made the announcement on MTV and on black radio the following morning.

“We got sandbagged,” he said. “And being that we got sandbagged, the group is over today. It’s out of here…We stepped out of the music business as a boycott of the music industry—management, the record companies, the industry, retailers—[now] everybody [is] involved in the enforcement for us to make a decision for our group instead of us carrying out our disciplining of a person in our group our way.” On the black-owned New York radio station WBLS-FM, he said that the group had been “white balled,” inventing racy marketing copy to the end. Privately, Chuck D. said that Griff sabotaged the group out of jealousy.

Even the announcement that Public Enemy had disbanded did not abate the hysteria, which by now had its own momentum. The death threats continued, as did the flow of contradictory and even false information. Chuck D. told MTV’s Kurt Loder that Columbia “has the next [Public Enemy] album [Fear of a Black Planet], and won’t let it go.” This was patently untrue. Greene Street Studios in SoHo had not even scheduled Public Enemy to begin final work until July, and has since pushed the dates back to August. This was the sort of falsehood that could easily be checked; sources inside Def Jam, Columbia, Rush and PE’s independent publicist all contradicted Chuck D.’s claim. Though he denies this to be the case, part of Chuck D.’s problem all along may be that he expects not to be challenged. For all his belligerence on record and video, in conversation he is a windy but also very friendly man, with his own blunt charm (we met for the first time after he had publicly threatened me on several occasions; in person, he managed to backpedal from his threats without losing face). He is not antagonistic except in private or when surrounded only by allies. He and Public Enemy have taken on giants, but only from a distance; Chuck D. does not show a taste for the give-and-take of debate. (Griff does, and has the resources for it, which may explain why Chuck D. avoided him for so long.) “Chuck’s the kind of guy,” says Shocklee, “that’ll beat your ass, and the next day say, ‘whassup?’ Griff’ll beat your ass and not say anything.”

Around the group, the maelstrom continued to swirl. It was, as critic Robert Christgau pointed out, almost exactly 10 years since Elvis Costello had referred to Ray Charles as “a blind, ignorant nigger” (and 11 years since Mick Jagger had sung, on the title track to the Rolling Stones‘ Some Girls album, “Black girls just wanna get fucked all night,” and easily brushed off the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s attempts to get the group banned from black radio). Public Enemy’s slurs caused a louder bang.

On the group’s behalf, Sharpton announced a June 28 rally at Brooklyn’s Slave Theater to protest the role of Jews in stifling an important black voice, and threatened direct action against Columbia. “I think that unquestionably the whole record and movie industry is controlled by Jews and unquestionably they [Public Enemy] have been targeted by that group,” Sharpton told Smith, just days before being indicted on 67 counts of fraud and misconduct. “Al’s cool,” says Chuck D. “We’ve dealt with him before.” But according to Shocklee, the secretary from Public Enemy’s office sent Sharpton a request to cancel the rally. Even Griff did not attend.

On Friday, June 23, the group performed an unscheduled set at an N.W.A. concert at the Philadelphia Spectrum, announcing that it was their last show ever. Griff was in the wings, but did not go onstage. A week later, they performed again in Chicago—to fulfill a prior commitment, according to Chuck D. While in Chicago, Griff and Chuck D. met with Farrakhan, who reportedly slapped their wrists and told them they were in over their heads, that they were not ready to address the issues they had raised. He also told Chuck D. that if the rapper was going to be a leader, he should lead his group. It was the first sound judgement anyone had offered.

Stripped to its basics, this is a vicious recasting of a familiar rock’n’roll story: petty jealousy and resentment come between friends once they become successful, and a group gets eaten up by its own notoriety. “It was journalistic wilding,” says Stephney, another PE member eager to shrug off responsibility that, as the incident proves, cannot be shrugged off. The same mechanisms that blew the group up larger than life also blew up its mistakes; Public Enemy, like many acts or public figures before them, tried to resolve or ignore those problems as if they still existed on a small scale.

The remaining questions inspire only banal solutions or simple recastings. Why did the group wait so long to fire Griff? According to Shocklee and Stephney, they were all just confused as to why Griff, knowing the severity of the situation, had made the comments. No one was talking to Griff. “Finally I just asked him,” says Stephney. “I said, ‘Do you really believe that Jews cause the majority of wickedness across the globe?’ He said, ‘No that’s silly. I was just having a bad day. I was mad at the group.'” Once they learned this, they say, they moved to fire Griff.

As to whether they knuckled in to outside pressure, the question assumes a faulty metaphor. As a pop act and a business, Public Enemy exists less as an entity than as a series of relationships, some accidental; the polarity between inside and outside does not hold. Chuck D. said his biggest regret was the turmoil he had caused Spike Lee. Shocklee, more emotional, says, “You had death threats in people’s homes. We work in a studio where people bring their babies. What if some crazy person threw a bomb in there? Don’t talk to me about knuckling under.”

Meanwhile, Chuck D. has a short vacation in Roosevelt, his first in a long time. “Over the last two years,” he says, “I’ve spent more time with the group than with my family. That’s changing lately.” He is planning to buy a house in the next few months. He also talks of changing Griff’s status to probation; more than anything, he wants the group back as it was.

The negotiations with MCA are still moving forward. “If you took a poll of black people in Illinois,” says Chuck D., “they wouldn’t know anything had happened. You should go out there and do a survey. My album had its best five-day period while all this was going on. I’m about to have the number-one 12-inch in the history of Motown Records. Everything already is as it was.” It was an encore of the bluster in the face of reality that had allowed all the problems in the first place, or maybe just a little attitude for a reporter. Either way, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back had been selling at around 4,000 copies per week. “That record was dead,” says Russell Simmons.

Fear of a Black Planet is still scheduled for October release, with single, “911 is a Joke” backed with “Revolutionary Generation,” optimistically slated for August, though the group has remained out of contact with Columbia. Chuck D. says he has not made up his mind whether the latter song will be about RJ Smith. Also in the works is a Flavor Flav solo album. “Nobody hates me,” the rapper told Russell Simmons. “I’m Flavor the Friendly Ghost.”

As the incident blew over, at least for the moment, even Mordachai Levy moved on. The new message on his answering machine ran, “Finally, Al Sharpton, the anti-Semitic windbag, has been arrested. Let’s go to the trial and make sure justice is done, and Sharpton is thrown into jail. If you’re interested in marching on his home with us, leave your name and number at the sound of the tone….Sharpton hates Jews, but we hate Al Sharpton. Thank you, and never again.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post Public Enemy: Our 1988 Interview With Chuck D and Flavor Flav appeared first on SPIN.