I think the simplest way to describe George Smith Patton junior is in his own words: as “an outgoing introvert”. He was a poet and a life long klutz, constantly bruising himself and falling off his polo ponies. An Olympic athlete and swimmer, he lost a marksmanship competition in the Stockholm games of 1912 because he was too accurate - the judges ruled his later bulls eyes, which went through the same holes as his earlier bulls-eyes, were misses. They were not.

In 1932 Patton led the U.S. Army’s last cavalry charge - against a “bonus army” of protesting U.S. army World War One veterans. He was a lifelong anti-Semite, who smuggled a copy of Hitler’s anti-Semitic “Nuremberg Laws” back to the United States so it could be preserved as an example of the dangers of religious bigotry.

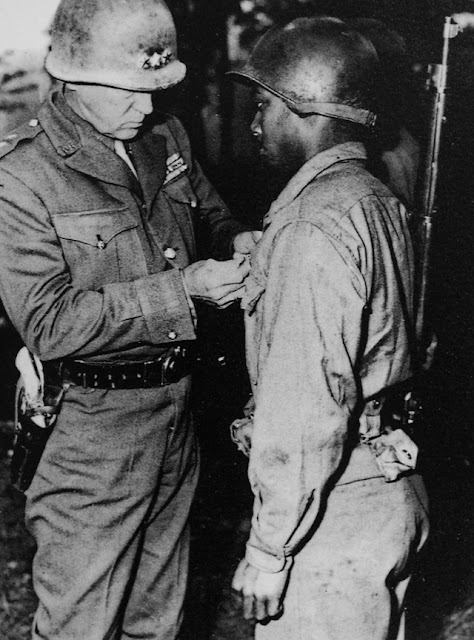

His father served under Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart, and a great-uncle was wounded at Picket’s Charge, defending black slavery. But while others refused, Patton requested a regiment of Black tankers be assigned to his Third Army. He put them in combat and praised their abilities.

Between mid-July 1944 and May 1945 Patton's 3rd Army moved further and faster than any army in history. Patton's soldiers captured 765,000 German soldiers, killed 144,000 and wounded 387,000 more. In late May of 1945, when he made a brief trip home to Los Angeles, he was greeted by a parade and a cheering crowd of 100,000 at the coliseum. But despite his contributions to the victory, on 2 October, 1945 George Patton was removed from command because he refused allow Germany to starve (Joint Chiefs of Staff directive #1067).

The orders of his dismissal were insulting and they were meant to be. General Eisenhower forbid Patton from making any public statements or to speak to the press on any issue. As a result there was no explanation as to why he had suddenly lost his beloved Third Army. But he was still assigned to Europe, which kept him out of sight and away from microphones back in America. It was as if General Eisenhower was already running for President.

On the Saturday before he was scheduled to return to the United States for the Christmas holidays Patton had dinner with his chief-of-staff, Major General Hobart R. “Hap” Gay. According to Gay, Patton had reached a momentous decision. After a lifetime of service, “I am going to resign from the Army,” Gay quoted Patton as saying. “For the years that are left to me, I am determined to be free to live as I want to and to say what I want to”. Patton had inherited a family fortune and he now intended to use the independence that money provided to finish his memoir, “War As I Knew It”, and tell his “unvarnished truth” about Eisenhower and General Marshall and General Omar Bradley. Had he done so, there can be little doubt, Patton would have shown himself to be a complicated conservative politician.

The next day, Sunday, 10 December 1945, Gay and Patton set off at 7 a.m. for a hunting trip in the forests outside of the Bavarian Cathedral town of Spry. It was a cold and overcast morning.

They traveled in two vehicles, a half ton truck driven by Sergeant Joe Spruce with their luggage and rifles, while the Generals rode in a 12 foot long 1938 Cadillac Fleetwood sedan, all steel and chrome with a spacious interior, powered by a Detroit V-6 block engine, and driven by Patton’s regular driver, 20 year old Private first class Horace L. Woodring. Fewer than 600 of these cars had been built and how this one got to Europe is unknown.

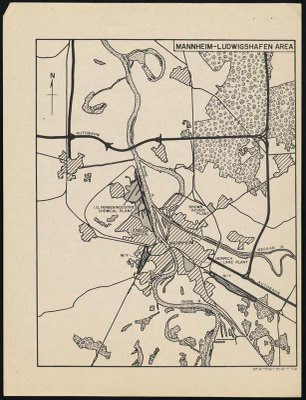

Part of the limousine’s stylish additions included a window and divider between the driver and the passengers’ compartment, and a small rectangular silver plaque on the divider with the word “Fleetwood ” embossed in sweeping script. About 11:30 they exited the autobahn at Mannerheim and took route 38 south.

On the outskirts of the devastated city the two vehicle convoy came to the multiple tracks of the bombed out railroad yards (above). Here Sergeant Spruce sped ahead, while the Cadillac was required to stop for a short freight train. Woodring then crossed the tracks and resumed his speed of about 30 miles an hour.

He wrote later that the road was clear ahead except for an on-coming 2 ½ ton truck – a deuce and a half – about a half mile up the road. Stretching along both sides of the road was the overflow from a quartermaster’s tank repair depot - burned out and broken tanks parked on both shoulders.

As they sped past this detritus Patton, who was sitting on the right side of the rear bench seat, commented on the wastage of war. One tank caught his attention and he turned his body and pointed off to the left, saying, “And look at that heap of rubbish”. Gay turned to look to look and so did Woodring, the driver. It was 11:48am, local time

The approaching truck suddenly turned to its left, into the repair yard, directly across the path of the Cadillac. Woodring slammed on his brakes, but it was too late. At impact the truck was going no more than 15 miles an hour - the Cadillac probably less than twenty. But nobody in either vehicle was wearing a seat belt. The big Cadillac slid a few feet and then thudded into the right side of the truck's external fuel tank. The impact was so light that the fuel tank was not even cracked.

The front chrome grill of the Cadillac however was shattered like a boxer's front teeth, and the left front wheel hub was twisted and broken off, revealing the tire beneath (above). But the massive steel frame of the Cadillac then performed its unintended function and transferred most of the force of the accident directly to the passengers’ bodies. Sitting in the backseat, General Gay was thrown forward and then back against the seat. And Patton, who was already leaning forward and half turned to his left, was thrown off the bench seat and fell against the divider, his forehead striking the Fleetwood plaque, tearing a small section of skin and bending his neck sharply backward. In recoil he then fell across Gay on the seat.

Patton (above left) immediately asked Gay (above right) if he was hurt. “Not a bit, Sir”, Gay assured him. Gay then asked, “And you, General?” Patton immediately replied, “I think I’m paralyzed. I’m having trouble breathing, Hap.” Woodring helped Gay out from beneath Patton, made sure help had been summoned. He then approached the driver of the truck, Private Robert Thompson. Woodring would later contend that Thompson was drunk, but Patton insisted that no actions be taken against the truck’s driver.

A doctor and an ambulance quickly arrived, and at 12:45 p.m. Patton was admitted to the 130th Station Hospital at Heidelberg, Germany. An x-ray instantly revealed what the doctors suspected; a simple fracture of the third vertebra with a posterior dislocation of the fourth vertebra, also known as the Hangman's Fracture.

In short, Patton had broken his neck and was paralyzed from there down. There was still a chance he could recover, but the doctors could not be certain until the swelling of his spinal cord had gone down.

Patton was taken to surgery and two “Crutcheld” (fishhook) tongs were inserted below his cheek bones to apply traction to his neck. By the next morning the traction had reduced the dislocation, but the swelling had not yet gone down.

To the constant stream of senior officers who visited him, Patton was cheerful. In private to his nurse he was depressed and frightened. Eisenhower did not visit, nor did Patton's immediate superior, General Bradley . Then on the morning of 12 December Patton reported that he could move his left index finger, slightly. His wife arrived that morning, having been flown from California. She warned the doctors that the General had a history of embolisms.

On 13 December 1945, Patton showed strength in his left arm and right leg. But that was as far as the improvements were to go. Abruptly the sixty-one year old began losing ground. He was given plasma and protein, as albumen. On 20 of December Patton reported trouble breathing. An X-ray confirmed that he had a blood clot in his right lung. He was now suffering from pneumonia and was placed on oxygen. Late on 21 December, 1945 Patton whispered to his wife, “It’s too dark. I mean too late.” Shortly afterward he died, from injuries which could have been prevented with a simple seat belt.

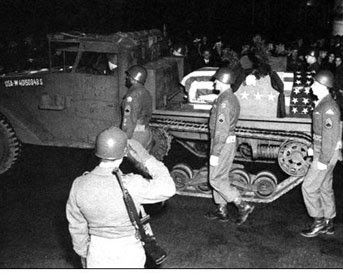

The official cause of death was listed as heart failure. On Christmas Eve, 1945, in a pouring rain, General George S. Patton was laid to rest in the U.S. military cemetery at Hamm, Luxembourg. As the casket was lowered a chaplain repeated one Patton's favorite sayings: "Death is as light as a feather."

I would prefer to remember General George S. Patton by something else he said. “Anyone, in any walk of life, who is content with mediocrity is untrue to himself and to American tradition." But I fear I will always remember that but for a simple seat belt, it was, as he once predicted, “A hell of a way to die.”