Just south of Hadrian’s Wall, the ancient stone barrier that cuts across England from coast to coast, is a Roman fort called Vindolanda. Built around 85 A.D. and occupied for more than 300 years, Vindolanda was the tense interstice between empire and unoccupied frontier—a largely self-contained city at the edge of the Roman world. Today, surrounded by green, picturesque countryside, it is a wellspring of insight into the human past.

Thousands of wooden objects have been found at Vindolanda, most of them mundane—bits of wheels, remnants of furniture, a toilet seat. Rob Sands, an assistant professor in archaeology at University College Dublin, was recently examining these objects for an upcoming exhibit when he came across one particular artifact and did a double take. The artifact’s official description labeled it as a darning tool, a crafting device that helps secure fibers and can be shaped like a mushroom or maraca. But to Sands, the “darning tool” looked much more like a wooden penis.

Sands made that hunch official last month, when he and Rob Collins, who had been researching phallic stone carvings from Vindolanda, published a reinterpretation of the ancient object as a disembodied phallus. They proposed three possible functions for the wooden carving based on an analysis of its most-worn areas, details of its shape, and the cultural context in which it was created: a decorative good-luck charm, a pestle, or most provocatively, a dildo. Collins, a senior lecturer at Newcastle University, in England, told me that the first time he had closely examined the nearly 2,000-year-old object, he’d noticed “some really interesting wear patterns” that were highly suggestive of a use quite distinct from sewing. “This doesn’t prove anything,” he told me, but it reinforced the possibility that the object might have, in his words, a “business end.”

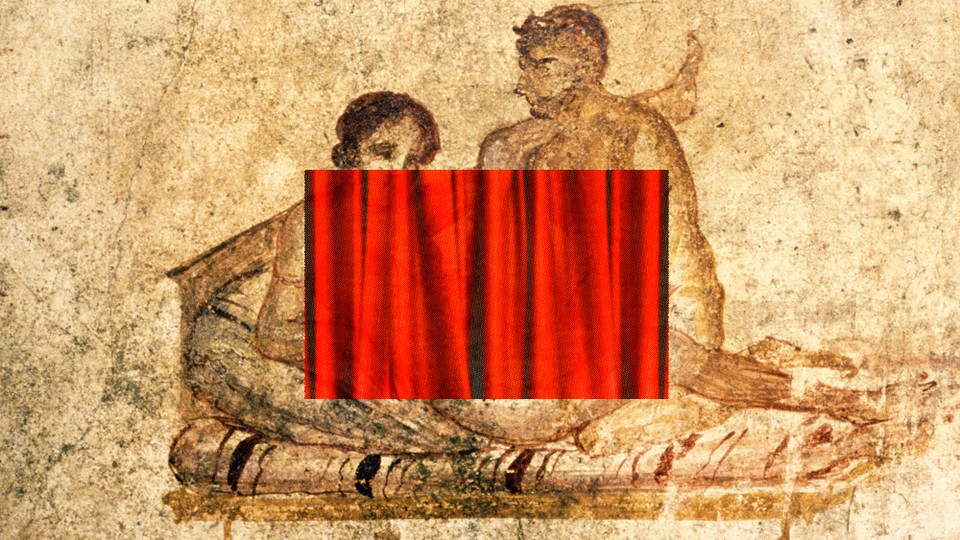

If the Vindolanda phallus is what Collins thinks it might be, then it’s the first Roman object identified as such. Ancient sex toys, generally, are hard to come by. There are rare exceptions—like a stone dildo found in China dated to about 600 A.D.—but most definitive examples are more recent, like sex toys from around the 18th century in France and Japan. Yet representations of sex toys in art and texts abound; for instance, in one Greek play from the third century B.C., two women discuss a scarlet-leather dildo and how much they enjoy it. This kind of evidence strongly suggests that these objects existed in antiquity. So what has archaeology been missing?

[Read: Victorian-era orgasms and the crisis of peer review]

It’s possible that most ancient sex toys were made from organic materials and, as a result, haven’t survived: A leather dildo, or even a wooden one, has the odds stacked against it. The Vindolanda phallus happened to be preserved only because of particular soil conditions caused by repeated building on the same spot. But even when genitalia-shaped objects do survive, Collins said, they tend not to be seen as sexual—and many of them likely weren’t. We can’t always determine an object’s purpose based only on its shape: Plenty of old and modern objects are, to varying degrees, penis-shaped without having a sexual use, or sexual without being penis-shaped. In their paper, Collins and Sands cited a few other examples of ancient wooden phallic objects—recovered in Egypt, China, and Japan—none of which are categorized as sex toys.

Determining whether a particular object was used for sex can be challenging. Ideally, you’d be able to reference supporting documents, such as a mosaic or poem depicting its function, says Rebecca Fasman, a curator at the Kinsey Institute, which focuses on research related to sex. For example, the Kinsey Institute houses a five-inch-long Egyptian terracotta phallus that Fasman says might have been used sexually. The supporting evidence for that theory: It’s life-size—too big to be a good-luck talisman, too small to be art—and lacks the adornments of other commonly found phallic objects, such as wind chimes. But the artifact may have served a different purpose, or even multiple purposes, Fasman told me. Perhaps it was attached to a larger sculpture as a charm to ward off evil or a symbol of fertility.

As Collins and Sands see it, however, the fact that sex toys are missing from the archaeological record may say much more about how ancient people are studied today than how they actually behaved. Until the late 20th century, Collins said, most archaeologists were reluctant to consider the possibility that an artifact might be a sex toy at all. Prudishness and propriety limited how researchers could decipher objects and past cultures, Collins argues, with “only certain interpretations deemed acceptable for a wider public.” In the 1930s, for example, a classics scholar and poet named A. E. Housman tried to publish an examination of Roman homosexuality, but it was turned down for being too salacious, says Kelly Olson, a classics professor at Western University in Canada. These attitudes restricted people’s understanding of not just antiquity but also a fundamental part of our human story—the search for sexual pleasure.

[Read: A twist in our sexual encounters with other ancient humans]

After the sexual revolution of the 1970s, research on ancient sexuality picked up in the 1980s. Marianne Moen, a Viking expert at the University of Oslo, told me that this was a period of reassessment—through the lens of sex and gender, archaeologists could interpret historical events and artifacts in a new way. Third-wave feminism and the queer-studies movement of the 1990s also had more mainstream scholars thinking more about sex, Olson told me, but enthusiasm for sexual archaeology soon waned thanks to backlash against those movements, Moen said. Even today, the public isn’t completely on board with the idea that the Vindolanda phallus may be a dildo: Some non-archaeologists have scoffed at the possibility of its sexual use, and Collins has received some aggressive emails pushing back on his interpretation. Some people, he said, simply don’t like the idea of a dildo being wanted in a Roman fort because its potential use would suggest that male anatomy wasn’t necessary (or sufficient) for pleasure.

Archaeologists “always have to be careful not to project our contemporary values and expectations onto past societies,” Collins said. If he were an archaeologist in the 1970s and encountered the Vindolanda phallus, he told me, he might not even have known what a dildo was, and likely would not have thought to label an ancient artifact as one. At the same time, present-day researchers have to be careful not to project a modern view of sexuality onto the ancients. Fasman told me she doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that researchers are able to suggest the Vindolanda phallus is a dildo when it’s easier than ever to spot and buy a sex toy.

If Sands and Collins are correct, their reinterpretation of the phallus, along with other reassessments of ancient art, objects, and texts relating to sex and gender, show how easy it can be for researchers to overlook something in plain sight—whether that’s ancient Greek authors’ love of a dirty joke or the concept of gender fluidity in the La Tolita-Tumaco culture, of what is now the borders of Colombia and Ecuador. Olson pointed out that if the Vindolanda phallus is indeed a sex toy, its form and wear suggest it was better suited for clitoral stimulation than anything else—a rare (or rarely noticed) sign of female sexuality in antiquity. Details like this help expand our awareness of ancient sexuality beyond stereotypes.

[Read: Before vibrators were mainstream]

Fasman and Olson said it’s fair to assume that museums and institutions outside Vindolanda house unlabeled dildos too. The National Archaeological Museum in Naples, for example, hosts an impressive collection of objects that are considered to be erotic art but may have had a more hands-on use. Much of it was found in Pompeii in the 18th century, a time when early archaeologists would not have ventured to classify artifacts as sex toys. In 1819, the art was called obscene and locked away; the general public was not allowed to see it until 2000. Every ancient object in a museum collection might be an opportunity for reinterpretation. “If this research kind of prompts a curator to go back and say, ‘Oh, that reminds me of something in our collection,’” Collins said, “that would be fantastic.”