Here’s an unexpected breakthrough—an animator draft/breakdown video of a pivotal film from Tex Avery’s directorial career at Leon Schlesinger’s!

Here’s an unexpected breakthrough—an animator draft/breakdown video of a pivotal film from Tex Avery’s directorial career at Leon Schlesinger’s!

Upon its release at the end of July 1940, Tex Avery’s A Wild Hare was a hit with American audiences, who were unaccustomed to seeing an audacious character like Bugs Bunny outsmarting gullible hunter Elmer Fudd with such cool aplomb. Within a few days after A Wild Hare reached theaters, the August 2 edition of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette touted the film as solid competition over Walt Disney for an Academy Award, reporting the new Schlesinger production as “the most amusing bit of animated nonsense in a blue moon.” Another Pennsylvania newspaper, The Shamokin News-Dispatch, labeled A Wild Hare a few weeks later as “one of the year’s best cartoons.”

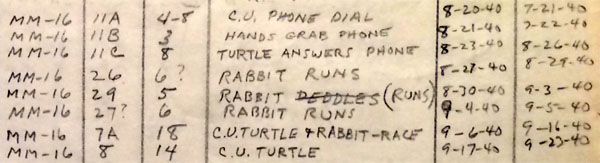

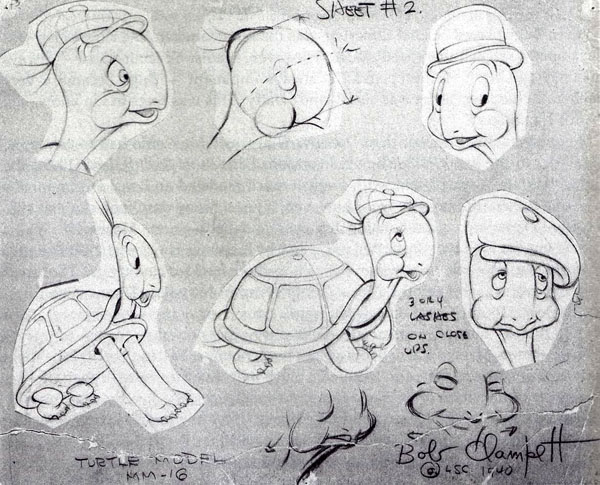

On August 20, animator Revalee “Rev” Chaney noted his involvement in scenes with a turtle and a rabbit—a takeoff on Aesop’s “The Tortoise and the Hare” as a new vehicle for Bugs Bunny—in his daily work ledger. Chaney continued work on his animation in this production until mid-September and resumed in early October after a brief commitment to another short.

By mid-October, the overwhelming public reaction to A Wild Hare established Bugs Bunny’s indisputable reputation as a new cartoon star. Trade publications announced the Schlesinger studio’s plans to feature Bugs in five subsequent cartoons due to exhibitor demands and to multiple bookings that A Wild Hare received in Fox West Coast Theaters. One of the confirmed titles in this group of five cartoons, Chuck Jones’ Elmer’s Pet Rabbit, was rushed into production that October and, shortly after, reviewed in Boxoffice magazine’s December 28, 1940 issue.

By mid-October, the overwhelming public reaction to A Wild Hare established Bugs Bunny’s indisputable reputation as a new cartoon star. Trade publications announced the Schlesinger studio’s plans to feature Bugs in five subsequent cartoons due to exhibitor demands and to multiple bookings that A Wild Hare received in Fox West Coast Theaters. One of the confirmed titles in this group of five cartoons, Chuck Jones’ Elmer’s Pet Rabbit, was rushed into production that October and, shortly after, reviewed in Boxoffice magazine’s December 28, 1940 issue.

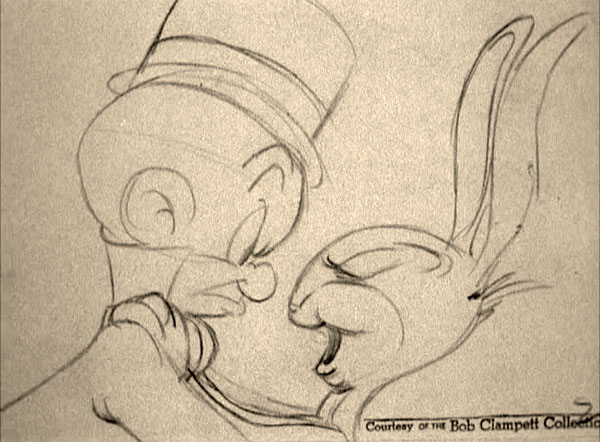

In Jones’s cartoon, Bugs Bunny’s name appears on-screen for the first time under its main titles (though marketing materials and copyright synopses used it before even A Wild Hare.) At first, the rabbit acts as a timid creature, enticing Elmer Fudd to purchase him at a pet store. However, Bugs is instantly exasperated at his newly domesticated lifestyle. Apart from his cantankerous demeanor throughout the short, Bugs spoke in an unusually different tone, comparable to the rabbit’s voice in Elmer’s Candid Camera, released earlier in March 1940 — in an Australian television interview, Mel Blanc confirmed that he devised his early Bugs vocals in Candid Camera to emphasize the rabbit’s overbite. For his first Bugs cartoon, Tex had attempted to establish a permanent “streetwise” voice for Bugs with Mel Blanc’s performance, heard in earlier Avery cartoons such as The Bear’s Tale and A Gander at Mother Goose (both 1940).

Pet Rabbit’s incongruities notwithstanding, its sequence of Bugs tricking Elmer into a couples’ dance, during Fudd’s failed attempt to evict the rabbit, remains the sole remnant of the rabbit’s mischievous nature from Avery’s iteration. Furthermore, in the concluding close-up to this sequence, Bugs caresses Fudd and speaks with a complimentary “You dance divinely, really you do,” a la Katherine Hepburn.

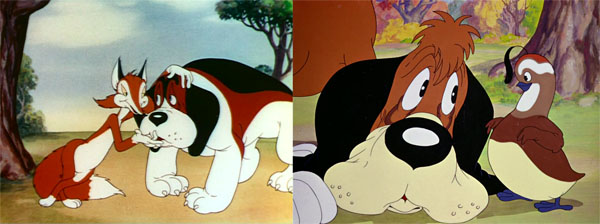

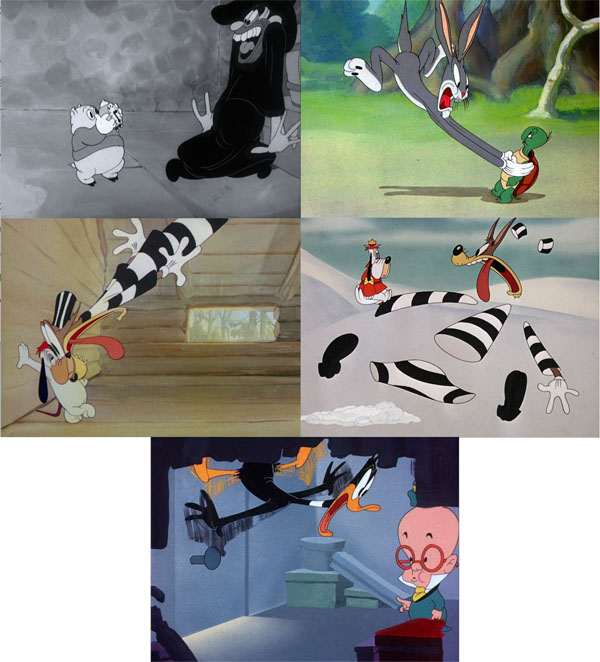

Meanwhile, Avery tried to replicate the success of A Wild Hare with a pair of cartoons featuring Willoughby, a slow-witted hound, with Tex providing his voice: Of Fox and Hounds (below right) and The Crackpot Quail (below right). In both films, George the fox and the titular quail are Bugs-like surrogates, with Blanc further developing his “streetwise” intonations. Like Bugs, the two characters continuously bedevil their dense canine aggressor, patterned after Lon Chaney Jr.’s role as Lennie in the 1939 film adaptation of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. (Willoughby made his final appearance in another Bugs cartoon directed by Tex, The Heckling Hare, released July 1941.)

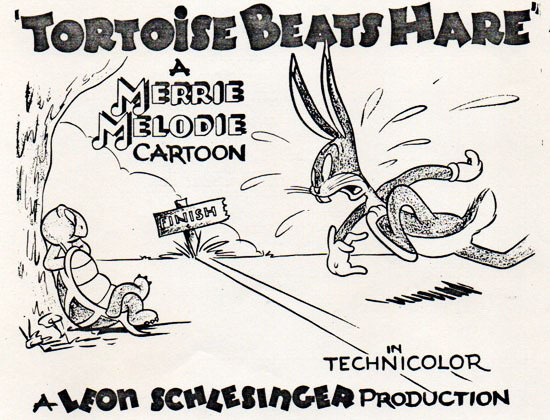

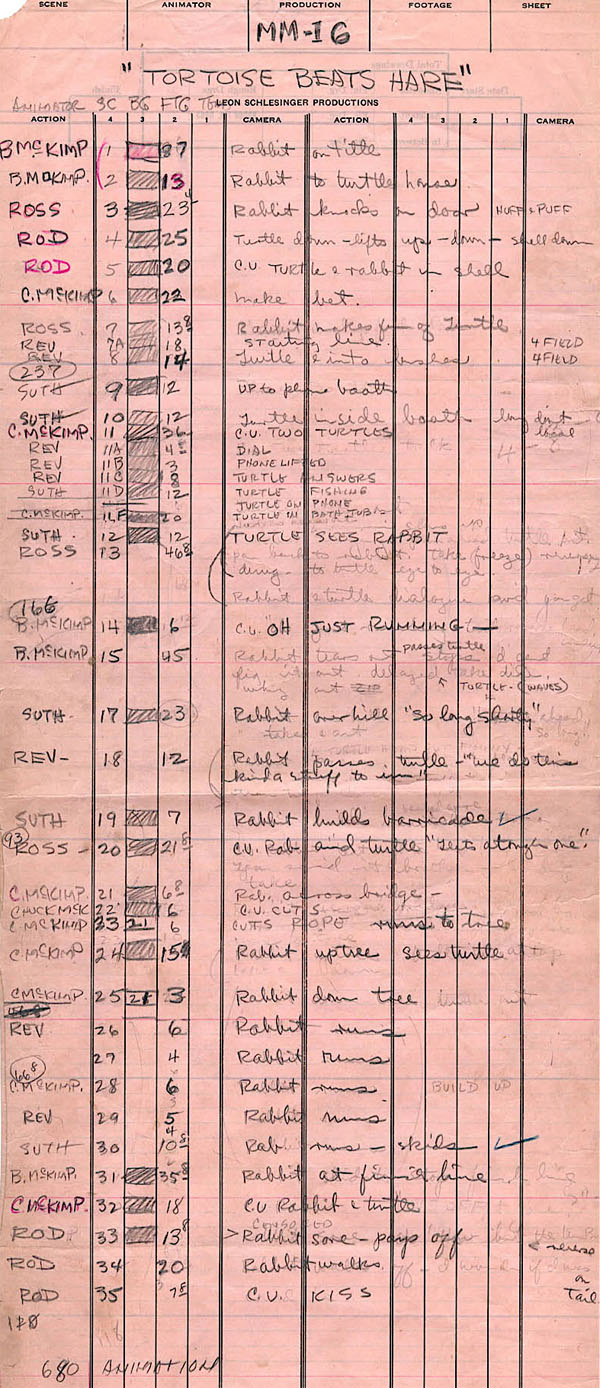

Regarding the pencil animation of a rabbit and turtle listed in Rev Chaney’s ledger (excerpt below), these belonged to another Bugs cartoon announced in the trades, Tortoise Beats Hare. In a 1971 interview, Bob McKimson, then in Avery’s unit, recalled: “Tex didn’t want to make another Bugs Bunny after the first one.” But, at the insistence of production manager Ray Katz, Tex complied with the order to produce a Bugs cartoon for “McKimp,” Avery’s nickname for the studio’s leading animator. McKimson continues, “He knew that I liked to animate on Bugs and liked to work with him, and so that was how come he made even the second one.”

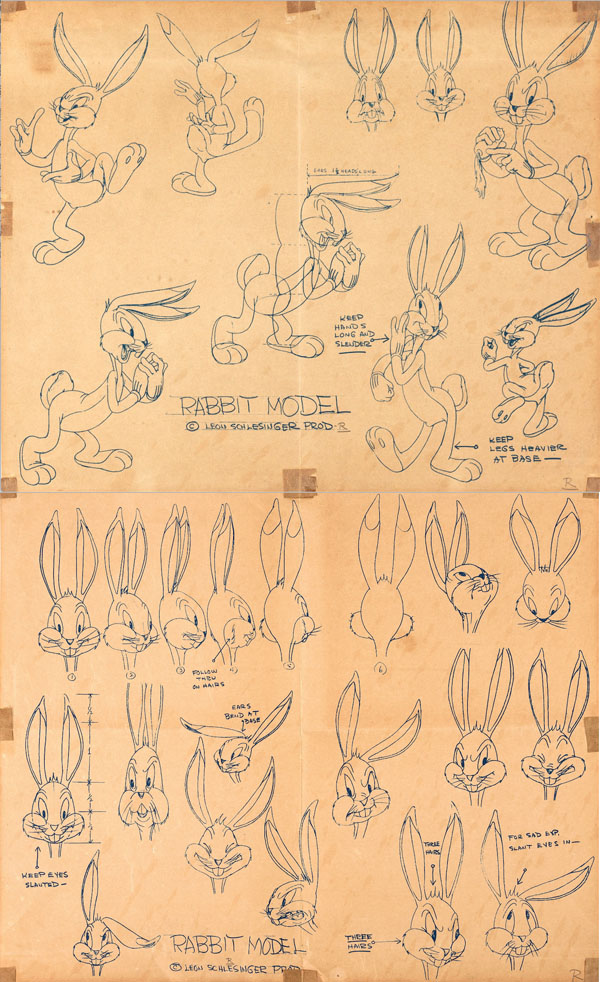

From September 16 to 20, 1940, almost a month after Chaney started work on Tortoise Beats Hare, Tex wrote in the lower margins of his production schedule, listing various future releases: “Model sheets – 1½ days – B. McKimp,” a signifier that McKimson drew the “rabbit model” that differed from “Tex’s rabbit” in A Wild Hare, designed by Bob Givens. Between late August and mid-September 1940, Avery’s animators likely used the Givens model to guide their scenes in Tortoise before Tex permitted McKimson to modify Bugs Bunny’s design slightly. Two days later, on September 22, Tortoise Beats Hare was inserted into Tex’s production schedule, listed under the working title “Tortoise + Hare.”

Avery’s directorial output for Leon Schlesinger paved the studio’s reputation as a foundation of edgy, innovative film comedy. But Tex’s trademark violation of film conventions reached a new level with the start of Bugs’ third cartoon, as moviegoers watched the carrot-chomping rabbit stride into the frame, obstructing the opening titles! In a delightful blend of Mel Blanc’s vocals and Bob McKimson’s precise draftsmanship, the rabbit stops to read the credits aloud, with a mouthful of carrot, mispronouncing the names of the principal artists in his latest picture, Carl W. Stalling excepted. Lasting nearly a full minute without cuts, the surprised Bugs “spit-takes” after seeing the film’s title, foreshadowing the conclusion of Aesop’s fable. Now incensed, the rabbit believes the tale is fabricated by a “big bunch of joiks,” meaning, in this context, its credited artists. (“And I oughta know, I woik for ‘em,” Bugs remarks to the audience.)

Tex’s inventiveness at Schlesinger’s was celebrated by his colleagues and influenced other animation workshops. For example, Paramount’s Famous Studios mimicked Tortoise’s opening for the start of The Hungry Goat, a Popeye cartoon released in 1943. As the cartoon begins, the eponymous goat strolls by the title card while he sings a little jingle but realizes something amiss and then asks the projector to rewind the film. He then reads the title card and notes that he must be hungry—now the cartoon can proceed. A few years later, Tex reprised this method in two MGM cartoons released in 1945, The Screwy Truant and the introduction of Swing Shift Cinderella.

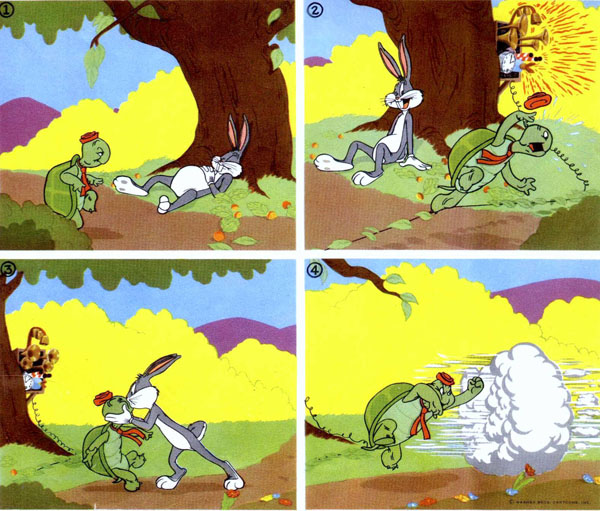

Avery’s Bugs Bunny in Tortoise is more destructive, markedly different from the composed rabbit in A Wild Hare. After tearing off the title card, Bugs searches for the turtle and impulsively opens and shuts the doors of various woodland homes before finding Cecil Turtle’s abode. The rabbit angrily pounds on his doorway; in his agitation, he assumes the role of the Big Bad Wolf, to his embarrassment. Virgil Ross, the animator of this scene, had worked with Tex at Walter Lantz’s studio in the mid-thirties. When Tex moved to Schlesinger’s in 1935, Ross — and Sid Sutherland, another animator in Avery’s unit — came along.

Rod Scribner, known for his extreme distortions and posing, is suitably cast in the scenes when Bugs bodily shakes (and deshells) Cecil’s carapace. Also animated by Scribner, Bugs wedges his head inside the turtle’s shell in a comical show of hubris. The rabbit proposes a $10 wager to the race winner ($214.89 in 2023 US currency), which Cecil accepts. Bugs derides his opponent at the starting line, dubbing him “Seabiscuit,” a champion racehorse of the era.

In later recollections, Tex Avery and fellow director Frank Tashlin—not present at Schlesinger’s during the creation of Bugs Bunny, having left in early 1938, not to return until 1942 — compared the rabbit’s brash personality to Max Hare from Disney’s Oscar-winning 1934 Silly Symphony The Tortoise and the Hare. Avery commented, “I practically stole it. It’s a wonder I wasn’t sued. The construction was almost identical.” Bugs’ personality and voice had a New York veneer, more strongly evident in this second cartoon than in A Wild Hare, far removed from the rustic hare in Disney’s film.

In a pair of scenes assigned to Rev Chaney, who was promoted to a full animator at Schlesinger’s in January 1940, Bugs promptly dashes off-screen, and Cecil trails behind slow and steady. The turtle visits a telephone booth, where he calls a relative, Chester Turtle, and asks him to spread the word about his race strategy. As the two turtles talk, Avery uses a simulated split-screen effect, broken when Cecil leans across the partition and orders him to give Bugs “the works.” Tex defied these filmmaking elements in his earlier Merrie Melodies Thugs with Dirty Mugs (1939), Cross-Country Detours (1940), and The Bear’s Tale (1940). Avery expertly mimics feature film techniques in the following montage sequence of Cecil’s cousins answering the call to action, set to a stirring orchestration of Mendelssohn’s overture from Athalia.

With one of the turtles in position, Bugs hops and glides along the dirt road; he passes by his opponent, who mockingly greets him as “Speedy,” parallel to Bugs’ earlier jabs at Cecil. After five seconds, as animated by Virgil Ross, the stunned Bugs freezes in place and zips back to the turtle, utterly perplexed and exasperated that his challenger outran him. Bugs removes the tortoise’s shell and hurls it off-screen. Then, he resumes the lead and stops to speak to the viewers, skillfully animated by Bob McKimson. “And there he was in front of me,” Bugs says, pointing to another turtle. In response to Bugs’ sudden shock, the turtle delivers an unexpected smooch to Bugs, reflecting the affronts delivered to Elmer in A Wild Hare.

Earlier in his career at Schlesinger’s, Tex used this omnipresence motif in a black-and-white Looney Tune with Porky Pig, The Blow Out (1936). Its situation, with Porky returning an alarm clock—a time-activated explosive device— to a mad bomber, acted as comic fortuity centered around our hero’s benevolence in exchange for pennies to purchase an ice cream soda.

Though the predominant backbone of the turtles’ contrived relays was secondhand from an earlier picture, Dave Monahan, the credited story man on Tortoise, remembered Tex devising a new angle on the recognizable fable for his second Bugs cartoon: “The idea was very simple, but it was just that magical slant you needed on a classic story.”

Speeding ahead of the tortoise, Bugs jeers at his opponent, whom he’s sure he’s outrun. A razor-sharp whip pan reveals the turtle—more accurately, another of the turtle’s relatives — far ahead. After Bugs blasts by, the tortoise turns to tell the audience, “We do this kind of stuff to him all through the picture.” From the beginning, characters who break the fourth wall—and distance themselves from their on-screen actions—by addressing their audience was one of Tex’s distinctive achievements in the animated cartoon—a reliable trademark throughout his livelihood. A few days after Tortoise premiered, the March 24, 1941 issue of The Hollywood Reporter described the turtle speaking to the audience, a la Groucho Marx’s “strange interlude” (which itself parodied the internal monologues of Eugene O’Neill’s stage production) in Animal Crackers (1930).

In his competitive efforts to impede his adversary, Bugs booby-traps the route with a barbed wire fence, a deep trench, and a barricade of large boulders and redwood logs. After that great accomplishment, the rabbit sees an extra turtle beside him. The hare cuts a suspension bridge tied across a canyon overlook and shimmies up a nearby tree to examine the view but is startled to find another tortoise above him. Each of Bugs’ failures generates more demeaning smooches from his enemy.

Ever relentless in his goal, the dogged Bugs races ahead of the tortoise without stopping, shown in three variant tactics through cross-dissolves and cuts. With footage split between Rev Chaney and Sid Sutherland, the two used caricatured actions for each of the rabbit’s exertions: on all fours like a genuine rabbit, literally hopping mad (scene 26); his legs blurring into a propeller-like action (scene 27); with the enthusiasm of an Olympic sprinter before skidding into the dirt across the finish line (scene 30). The production scene draft lists two more shots of Bugs running (scenes 28 and 29), assigned for pencil animation but not inserted into the finished cartoon—they might have been cut to help the pacing of its climactic moments.

Ever relentless in his goal, the dogged Bugs races ahead of the tortoise without stopping, shown in three variant tactics through cross-dissolves and cuts. With footage split between Rev Chaney and Sid Sutherland, the two used caricatured actions for each of the rabbit’s exertions: on all fours like a genuine rabbit, literally hopping mad (scene 26); his legs blurring into a propeller-like action (scene 27); with the enthusiasm of an Olympic sprinter before skidding into the dirt across the finish line (scene 30). The production scene draft lists two more shots of Bugs running (scenes 28 and 29), assigned for pencil animation but not inserted into the finished cartoon—they might have been cut to help the pacing of its climactic moments.

Finishing first in the race, the wearied rabbit looks behind him, and at last, the turtle is nowhere in sight. In a bravura performance by Mel Blanc—again coupled with Bob McKimson’s polished animation—Bugs gets to his feet, gasping for breath, and breaks into rapturous laughter over his victory. Unfortunately, this moment is short-lived; Cecil calls to “Speedy,” revealing the tortoise reclining under a tree—the tortoise has emphatically beaten the hare. Overcome with vehemence, Bugs squeezes Cecil’s neck tightly – from which the turtle breaks free to lower his hand awaiting payment. Begrudgingly, Bugs hands Cecil his winnings and childishly taunts him, protruding out his tongue before leaving, animated by Rod Scribner.

In the film’s closing moments, also handled by Scribner, Bugs puzzles over the results of the footrace, but suddenly, he stops to wonder if some trickery fixed the event all along. His suspicions are correct—with their cash in hand, Cecil and his cousins plant one massive group kiss on the loser as the film fades to black. (Viewers may notice Scribner’s model of Bugs shifts during scenes 33 to 35; since the directors did not usually assign scenes to animators in sequential order, it is feasible that Rod referenced the Givens model sheet for scene 33 with Bugs and Cecil, then adopted the McKimson “rabbit model,” after its approval from Tex, for scenes 34 and 35.)

Borrowing from popular culture, the final line spoken by the gang of turtles, “Mmmmm, it’s a possibility,” refers to a catchphrase by the radio character Mr. Kitzel, performed by comic actor Artie Auerbach, in programs featuring Joe Penner, Al Pearce, and Jack Haley between 1936 and 1940. (A year later, Tex reprised Kitzel’s signature line as an end tag, spoken by a chorus of hellish demons, in his first MGM release, Blitz Wolf [1942].)

Borrowing from popular culture, the final line spoken by the gang of turtles, “Mmmmm, it’s a possibility,” refers to a catchphrase by the radio character Mr. Kitzel, performed by comic actor Artie Auerbach, in programs featuring Joe Penner, Al Pearce, and Jack Haley between 1936 and 1940. (A year later, Tex reprised Kitzel’s signature line as an end tag, spoken by a chorus of hellish demons, in his first MGM release, Blitz Wolf [1942].)

A few months after Tortoise started production, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s premonition came true when A Wild Hare eclipsed Disney in the 13th Academy Awards at its ceremony on February 27, 1941. Disney forwent submitting any candidates that season after seven consecutive wins in a row, allowing other animation factories their chance at an Oscar. The Academy chose two MGM cartoons as nominees, Rudy Ising’s sumptuous fantasy The Milky Way and Puss Gets the Boot, Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera’s first (albeit uncredited) directorial job for Metro, featuring Jasper the cat and Jinx (or Pee-Wee, as named in publicity materials), who evolved into Tom and Jerry. Neither Puss Gets the Boot nor A Wild Hare won the award (the Oscar went to The Milky Way), but the two cartoons marked a revolutionary shift—a rebellious, fast-paced style that became the essence of 1940s animation. (The Academy screened, but did not select, the third breakthrough that signaled the new trend—Walter Lantz’s Knock Knock, the debut of Woody Woodpecker.)

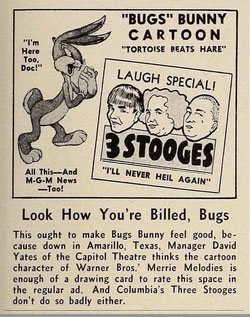

This ad from a paper in Cumberland, Maryland tells us where “Tortoise Beats Hare” was playing on July 14th 1941.

As evident throughout Tortoise Beats Hare, Tex experimented with Bugs’ development as a protagonist by reversing his personality traits from A Wild Hare. Instead of being a triumphant rascal, as in that earlier film, Bugs is flummoxed and humiliated by Cecil (and his cousins) as the desperate loser. The following year, Tex revisited this theme at MGM with Dumb-Hounded (1943) and its follow-up, Northwest Hounded Police (1946), featuring the basset hound Droopy, who had the deadpan attitude (and movement style) of Cecil. Droopy pursues a fugitive convict wolf in both films, materializing in their every hideout and escape route. Tex reprised the finale of Tortoise for Northwest, this time with a massive crowd of Droopy lookalikes! Before the release of Northwest, Warners issued Draftee Daffy (1945), directed by Avery’s protégé Bob Clampett. Owing much to Tex’s approach, the cartoon has draft-dodger Daffy reacting wildly and bolting away from the “little man from the draft board,” who shows up every instant our hero “ducks” for cover.

Earlier in the film, Bugs baits the tortoise to open his front door with the sarcastic nickname “Superman.” While Cecil was no comic-book superhero, his brief foray into the medium began with the second issue of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics in November 1941, in a straight retelling of Tortoise Beats Hare. As in Tex’s cartoon, Cecil calls on his cousin Chester Turtle, who connects all the other turtles in their family to initiate their scheme against Bugs. By the fifth issue (March 1942), Chester Turtle — drawn more realistically by artist George Kerr in the story “Remote Control” — became the default turtle featured in the comics afterward, possibly a response from the writers to the earlier Tortoise adaptation. From issue six (April 1942), Chester starred in featured stories as a married man with a wife and kids (see below), clearly inspired by turtles having large families. Chester’s stories continued in LT&MM through 1943, but the feature switched to one-page gags in 1944; Cecil’s cousin no longer remained a flagship character in the comics.

Though the chief directors and writers developed Bugs as a wise-cracking, confident, in-charge rabbit after Tortoise, the studio pitted him against Cecil in two later cartoons. While he plays the exasperated victim in both films, they spotlight Bugs’ appeal as an animation icon, specifically in the inspired acting of his animators. Apart from one instance of Bugs slapping Cecil into a twist in the first sequel, Tortoise Wins by a Hare, Bugs restrains from causing bodily harm to his adversary. Instead, Bugs externalizes his anguish by ranting and raving, expressing his vanity and urgency to disprove Cecil’s seeming skill. Tortoise Wins by A Hare, directed by Clampett, recycled footage from Avery’s cartoon as a narrative setup, as a furious Bugs analyzes the film, perturbed about how the “toitle” defeated him. (While Clampett’s film discounts the involvement of Cecil’s cousins in the lifted footage, the comic book adaptation in LT&MM #27, issued in January 1944, features Chester in the Cecil role.)

Without model sheets from Schlesinger available for reference, the pencillers responsible borrowed film prints and traced directly from a Moviola for the panel artwork.

Four years after Clampett’s Bugs-Cecil race, Rabbit Transit (1947), directed by Friz Freleng, completed the trilogy. In its first scenes, the modest Cecil knowingly incites the challenge when he overhears Bugs’ skepticism over the “Tortoise and the Hare” story. Unlike Tex’s original, where Bugs was an object of ridicule, both Bugs and Cecil rely on machinations before each race. In Tortoise Wins by a Hare, the two characters use makeshift disguises to hoodwink one another; Rabbit Transit had Cecil using a shell fueled by jet propulsion. Freleng—with writers Mike Maltese and Tedd Pierce—had both characters upstage each other via “tit-for-tat” retaliations. In one instance, Bugs, duped by the turtle, bursts from a gift box and reciprocates a large kiss as a present to Cecil!

In 1948, Capitol Records released Bugs Bunny and the Tortoise in their “Record-Reader” line of 78rpm shellac discs, intended for young readers to play the records while following along with an accompanying storybook (images above). In the twelve-minute saga, Bugs and Cecil endure a cross-country race. The rabbit stops to rest numerous times in the story: encountering a little duckling, becoming caught in a snare trap by Henery Hawk, and settling down for a nap after devouring rows of carrots cultivated in a field. Unlike the animated films, Bugs’ detours do not impede him from continually besting Cecil. In 2021, eighty years after Tortoise Beats Hare’s theatrical release, Bugs and Cecil’s timeless clash resurfaced in an episode of Looney Tunes Cartoons, “Shell-Shocked”—its proceedings occur in New York City, an apt locale for the urbanite rabbit.

NOTE: To watch the “Breakdown Video” below – click the “pop-out” button (upper right corner; square with arrow) – or click THIS LINK.

SPECIAL THANKS to Jerry Beck, Ruth Clampett, Michael Barrier, Keith Scott, David Gerstein, Tom Samuels, Norman Chaney, Frank M. Young, and Eric Costello for this post’s production materials and information.

But wait, there’s more exciting news! An annotated post detailing Tex Avery’s 1940-41 production schedule, with complementary fragments from Rev Chaney’s ledger, both vitally important documents, will appear on my Patreon page shortly—no subscription necessary.

1940E24. A Wild Hare (Bugs, Elmer)(294)[HBO Max].mp4 (485MB)

1941E01. Elmers Pet Rabbit (Bugs, Elmer)(311)[HBO Max].mp4 (320MB)

1940E07. Elmers Candid Camera (Bugs, Elmer)(277)[HBO Max].mp4 (488MB)

1940E38. Of Fox and Hounds (Willoughby)(308)[DVD].mp4 (74MB)

1941E06. The Crackpot Quail (Wiloughby)(316)[HBO Max].mp4 (340MB)

1936E08. The Blow Out (Porky)(127)[HBO Max].mp4 (273MB)

1943E04. Tortoise Wins By A Hare (Bugs, Cecil)(394)[HBO Max].mp4 (485MB)

1947E08. Rabbit Transit (Bugs, Cecil)(496)[HBO Max].mp4 (410MB)