In the winter of 1975, a quiet young woman from Lexington, Kentucky, met her Ph.D. adviser in Brown University’s writing program for a series of unsatisfactory tutorials about an ambitious project of hers that had yet to fully reveal itself. The encounters were strange enough that her adviser still recalled them in an interview a quarter century later: “I was doing all the talking, and she would sit rigidly, just bobbing her head in a regal manner. Yet there was a kind of arrogance to her. Perhaps it was the arrogance of an artist fiercely committed to a vision, but I also sensed a bottled-up black rage.” There’s nothing unusual about a young writer seething at the world, especially in the 1970s, when protests and bad attitudes about race, war, and university curricula were so de rigueur that they may as well have been taught at orientation. Likelier than not, his student sensed her (white) adviser’s judgment and withdrew in response—and didn’t think he had much to offer, anyway. While her natural range was virtuosic, his work consisted primarily of a host of popular paperbacks and magazine stories whose titles, including Dormitory Women and “Up the Down Coed,” accurately convey their subjects and sensibilities.

However mutually frustrating the meetings between Gayl Jones and R. V. Cassill may have been, his comment is most striking for having been made to The New York Times after her husband, Robert Higgins, slit his own throat when a SWAT team stormed their house in February 1998 to arrest him on a 14-year-old warrant from another state. Two decades earlier, Jones had been hailed as one of the great literary phenoms of the 20th century, only to then drop out of sight; just days before her husband killed himself, she’d reemerged on the American literary scene with a new novel that would become a finalist for a National Book Award.

Leaving aside the callousness of Cassill’s remarks (and the obvious question: What does “black rage” mean?), they violated the typical assumptions of academic privacy. That the reporter and his editors deemed Cassill’s observation useful in understanding Jones’s life does not confirm her anger so much as it affirms all there is to be angry about. No matter her insights and achievements, the frame through which she was viewed and understood by the white world remained the same. She sat silently as he read the early drafts of what would become her first novel. He talked. She left. He was flummoxed. She returned, because she had to. It could have been a Beckett play, almost funny until you lived it.

Fortunately, Jones also worked closely at Brown with a true mentor, the noted poet Michael Harper, who’d overseen her master’s degree and would become a lifelong friend. She received her doctorate in 1975 and published her first novel, Corregidora, the same year. The story is told by a 1940s Kentucky blues singer, Ursa, whose troubles with men are refracted through memories of slavery handed down by her matrilineal line:

My great-grandmama told my grandmama the part she lived through that my grandmama didn’t live through and my grandmama told my mama what they both lived through and my mama told me what they all lived through and we were suppose to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we don’t forget.

Or, as the protagonist, whose mother and grandmother were fathered by the same Portuguese slave owner, says at another point: “I am Ursa Corregidora. I have tears for eyes. I was made to touch my past at an early age. I found it on my mother’s tiddies. In her milk.”

What Faulkner saw in the haunted old mansions of Oxford, Mississippi, Jones saw in the ghosts of the Black dead. She was a pioneer in grappling with the contemporary legacy of slavery, and her debut was praised by the likes of John Updike, in The New Yorker, as well as a host of Black writers. “Corregidora is the most brutally honest and painful revelation of what has occurred, and is occurring, in the souls of Black men and women,” James Baldwin wrote.

Jones’s early novels were shepherded by Toni Morrison, then an editor at Random House, who’d dedicated herself to publishing Black writers, especially women. To put things in perspective, at the time Corregidora came out, Morrison had only recently published her first works of fiction, The Bluest Eye and Sula. She had yet to hit her stride as a writer, while Jones burst forth in her early 20s all but fully formed and requiring little editing. Jones needed a champion, however, someone who could understand and appreciate the sophistication of her approach to subject matter as well as language. “No novel about any black woman could ever be the same after this,” Morrison declared after reading the manuscript of Corregidora.

Richard Ford, who got to know Jones when they were both fellows at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, called her a “prodigy”: “History may have caught up with her, but she was a movement unto herself. Toni knew this very, very, very well when she published her.”

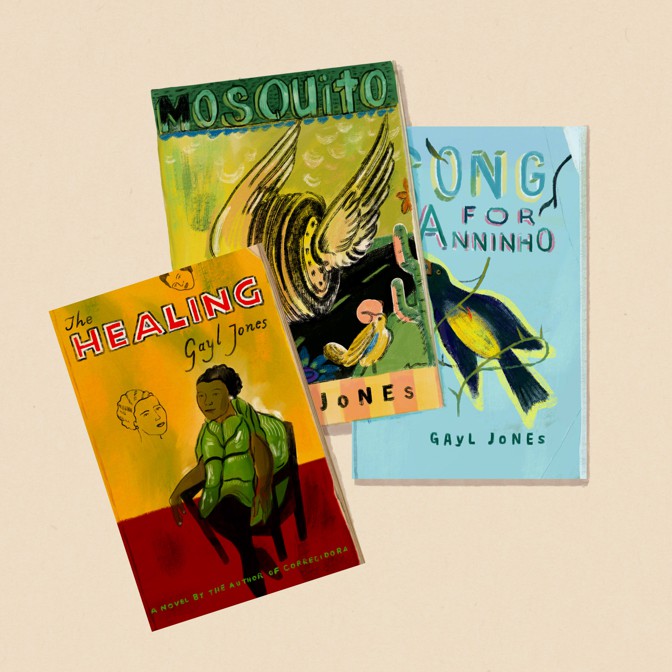

Jones had a marked effect not only on Morrison’s subsequent novels but on an entire generation of writers, whether they realized it or not. The tentacles of slavery in the present day have grown into a principal concern of Black literature, and Jones’s early work was absorbed into this canon almost imperceptibly. Over time, her literary ambitions would evolve, as she published and then receded from the public eye, published and then receded. This spring, she self-published her first novel in 21 years—Palmares, a six-volume work about the last fugitive-slave settlement in Brazil. In mid-June, Beacon Press bought the rights to the book, with plans to release it in September 2021.* In the sprawling narrative, set in the 17th century, Jones’s feats of linguistic and historical invention are on ample display. Describing the impact of her singular vision and intensity, John Edgar Wideman remarked 22 years ago: “I think she scared people.”

Gayl Jones was born into a modest family in 1949. Her father, Franklin, worked as a line cook in a restaurant, an occupation she would later give to the father of the narrator of her second novel, Eva’s Man. Her mother, Lucille, was a homemaker and a writer; Jones would incorporate lengthy passages from her work into her experimental fourth novel, Mosquito.

Jones spent childhood weekends visiting her maternal grandmother on a small farm outside Lexington, where she absorbed the stories of the adults around her. It is an unremarkable detail, save for the importance and seriousness Jones later ascribed to this time, as an educated woman channeling those locked out of institutions of so-called higher learning, as a daughter in communion with her mothers, as a formidable theorist validating the integrity and equality of oral modes of storytelling. “The best of my writing comes from having heard rather than having read,” Jones told Michael Harper in an intimate interview conducted the year Corregidora was published. She hastened to add that she wasn’t dismissing the glories of reading, only pointing out that “in the beginning, all of the richness came from people rather than books because in those days you were reading some really unfortunate kinds of books in school.”

In the mid‑1960s, when Gayl and her younger brother were teenagers, Lucille managed to enroll them in the segregated but academically well-regarded Henry Clay High School. (The public-school system in Lexington did not formally integrate until the mid-1970s, 20 years after Brown v. Board of Education.) Jones proved an extraordinary student, and through the efforts of her Spanish teacher she was introduced to the poet Elizabeth Hardwick, who, together with her sometimes husband, Robert Lowell, helped arrange a scholarship for Jones at Connecticut College. She proved an equally exceptional student in New England, devoting herself to literature.

Jones published Eva’s Man in 1976, a year after Corregidora. Like Ursa, Eva is a 40ish woman recounting her life story, in this case from prison. Eva landed there after murdering and castrating in graphic fashion a lover she’d spent a few days with—ostensibly because she’d learned he was married. In conversations with a fellow inmate and a prison psychiatrist, Eva “stitch[es] her memories and fantasies into a pattern of sexual and emotional abuse,” as the critic Margo Jefferson wrote. When the psychiatrist asks Eva if she can pinpoint what triggered her to kill the man, she replies only, “It was his whole way.”

Jones called Corregidora a “blues novel,” because it communicated the “simultaneity of good and bad, as feeling, as something felt,” she told Harper. Meanwhile, she considered her second novel a “horror story,” explaining in another interview—with Charles H. Rowell, the editor of Callaloo, an African American literary magazine—that what Eva “does to the man in the book is a ‘horror’ … Eva carries out what Ursa might have done but didn’t.”

Published back-to-back, the books form a diptych exploring the undercurrents of the psyche in a world of slave-owners, whoremongers, prostitutes, killers, man-eaters, jealous husbands, wayward wives, psych-ward inmates, pedophiles, wife-beaters, women in love with their abusers, and girls who carry knives. Nobody goes to church much.

Instead of sermons, sense and sustenance flow from a web of intimacy and memory, at least for Jones’s female characters. The men are mostly phalluses tumescent with bad news. Their collective role is as a source of fear and pain, but also desire. Love is not absent, but the word can’t capture what transpires between her women and men. Jones has often been read as a political warrior speaking for unvoiced Black women, but she’s too great a writer with too broad a mind—and too mesmerized by psychological complexity—to pass any ideological purity tests. As she told Rowell, her preoccupations were “contradictory character and ambivalent character, and I like to explore them even without judgments entering the work.”

Jones’s politics are inscribed in her choice to write about the lowborn and low-down, giving them as much intelligence as she possesses; to work in flawless Black English; and to position herself inside rather than outside her characters. The vantage stands in contrast to the approach of Zora Neale Hurston, for example, whom Jones admired for her up-close treatment of relationships between Black men and women, but who at points wrote on behalf of Janie, in Their Eyes Were Watching God, not as her. As Jones well understood, Hurston, like all writers, was a product of her time, and of the circumstances of her oppression. She and her fellow members of the Harlem Renaissance were self-consciously striving to create a literature of Black people’s expanding worlds beyond slavery, but the mission could devolve into representing Blacks for a white audience, giving their fictions an unintended stiltedness. The problem might be summarized as one of code-switching between the Black world and the white gaze. The Black writer who knows the codes of both must always explain the lives, decisions, and humanity of her Black characters to whites who might not otherwise credit them. In Jones’s storytelling, however, there was no “ ‘author’ getting in the way,” Morrison noticed.

The other Black inventors of the modern novel about slavery were Leon Forrest (Two Wings to Veil My Face), who wrote with lyrical, epicurean elegance, and Charles Johnson (Oxherding Tale), whose stories of slave escapes are entwined with the Buddhist quest to get off the wheel of suffering, as well as with the ontological questions of Western philosophy. They bring the high-minded into the lives of the low. By working the other way around, Jones challenges literature itself to embrace other registers of the language, including the obscene, as in this relatively mild example from Corregidora:

A Portuguese seaman turned plantation owner, he took her out of the field when she was still a child and put her to work in his whorehouse while she was a child … I stole [the picture of him] because I said whenever afterward when evil come I wanted something to point to and say, “That’s what evil look like.” You know what I mean? Yeah, he did more fucking than the other mens did.

Jones elaborated on the politics of the English language with Harper:

I usually trust writers who I feel I can hear. A lot of European and Euro-American writers—because of the way their traditions work—have lost the ability to hear. Now Joyce could hear and Chaucer could hear. A lot of Southern American writers can hear … Joyce had to hear because of the whole historical-linguistic situation in Ireland … Finnegan’s Wake is an oral book. You can’t sight-read Finnegan’s Wake with any kind of truth. And they say only a Dubliner can really understand the book, can really “hear” it. Of course, black writers—it goes without saying why we’ve always had to hear.

Telling stories out loud was a matter of survival and wholeness for a community forbidden to read, as well as an act of rebellion, and the way Jones wields this tradition transforms even a kind of nursery rhyme shared between daughter and mother into something dirty, dangerous, and important.

I am the daughter of the daughter of the daughter of Ursa of currents, steel wool and electric wire for hair.

While mama be sleeping, the ole man he crawl into bed …

Don’t come here to my house, don’t come here to my house I said …

Fore you get any this booty, you gon have to lay down dead.

When Harper asked for her thoughts on the architects of 20th-century Black literature, namely “Gaines, Toomer, Ellison, Hurston, Walker, Forrest, Wright, Hughes, Brown, Hayden et. al,” Jones pointed out the wide variation in a group that to the mainstream might appear homogeneous:

You know, I say the names over in my mind, and I think about those people who will speak of black writing as a “limited category,” the implication being that it’s something you have to transcend. And it surprised me because I thought critics had outgrown that sort of posture.

She certainly had. Whereas Baldwin famously lashed out at the protest-novel straitjacket put on mid-20th-century Black writers—“The ‘protest’ novel, so far from being disturbing, is an accepted and comforting aspect of the American scene”—Jones came of age breathing the air of the Black Arts Movement. Founded by LeRoi Jones (no relation), who combined immense talent, critical acumen, and, after being brutalized by the police, a rusty shank of disdain for the lassitude of white America, the movement advanced the idea that white people’s approval was beside the point. Why bother being the Black exception in a country where attempts to control the mind and body of Black people knew no bounds? In his fiery 1965 manifesto, “The Revolutionary Theatre,” LeRoi Jones described the mission for Black artists this way: “White men will cower before this theatre because it hates them … The Revolutionary Theatre must hate them for hating.” Gayl Jones’s “fuck off ” was less explicit but no less radical: She wrote fiction as if white people weren’t watching.

Eva embodies that position. In a conversation about Jones’s second book published last year in The Believer, the young Zambian-born novelist Namwali Serpell explained the “brilliance” of Jones’s choice to let Eva be “bad,” to seemingly lack or reject the reflex to see herself through white people’s eyes. Eva’s “un-self-consciousness,” her unwillingness to “be known, or know how others know her,” Serpell said, “is a kind of freedom.”

More than a few readers of Jones have assumed that her volatile husband inspired Eva’s Man, but she didn’t meet him until several years after she wrote that book, in Ann Arbor. In other words, she wasn’t the naive Black girl writing autobiographical workshop fiction, an expectation Jones was accustomed to. “Always with black writers,” she told Rowell, “there’s the suspicion that they can’t … invent a linguistic world in the same way that other writers can.” A white professor, in fact, once told Jones that he was surprised that she didn’t talk more like Ursa.

Ford, who recalls Jones as “within herself, but friendly and very smart,” says it’s a mistake to conflate authors with their characters. “Gayl’s books were dramatic, sexual, sexually violent, eloquent, and harsh in their assessments of the life she was vividly portraying,” he told me. “But fiction is not simply an emotional ‘readout’ of a writer’s feelings. It’s a congeries of made-up, ill-fitting, heretofore unaffiliated shards of experience, memory, feeling, event.”

Not much is known about Robert Higgins, apart from the dramatic run-ins he had with the law, including a pivotal one in 1983, when the pair attended a local gay-rights rally. There, he was alleged to have proclaimed himself God and declared HIV a form of divine retribution, prompting a woman to punch him. Whatever actually happened, Higgins, being an American, went home and returned brandishing a gun. He was arrested by the Ann Arbor police; his assailant was not. Rather than appear in court to defend himself, he and Jones left town, with a letter of protest to the university (and to President Ronald Reagan) that said, in part: “I reject your lying, racist shit. Do whatever you want. God is with Bob, and I’m with him.”

The couple then decamped from the United States altogether and spent the next five years in Europe, mostly in Paris, joining the tail end of a Black expatriate scene made up of people who did not wish to return to America after World War II.

Around this time, Jones published three books of poetry. The best-known of these, Song for Anninho, shares the essential story of Palmares, the epic novel she began composing more than four decades ago. It’s a love story about a man and a woman who live there (and, incidentally, was dedicated to Higgins). In this faraway past in a world populated by Africans, American Indians, Europeans, and all their possible admixtures, Jones pursued her desire to link Black Americans’ struggle to that of colonized people across the globe—the goal of what’s known as the universal freedom movement. “I’d like to be able to …write imaginatively of blacks anywhere/everywhere,” she told Rowell. She was a passionate student of Latin American literature, and her poetry has the lushness—and at times the over-the-top romanticism—of pan-Americanists such as Eduardo Galeano and Pablo Neruda: “I struggle through memory … the blood of the whole continent / running in my veins.”

In the late 1980s, Jones and Higgins returned to America, moving to Lexington to live with Jones’s mother, who was ill. Meanwhile, the rights to Corregidora and Eva’s Man had been acquired by the old Boston publisher Beacon. In 1997, however, Jones asked her editor there, Helene Atwan, to remove them from print. “She said they portrayed Black men very negatively, and she didn’t want those to be her only books out there,” Atwan told me, admitting to being intimidated by her author’s brilliance. “I said, ‘No! They’re important books. Send us new books, and we’ll publish those.’ ”

Jones promptly forwarded the manuscript for The Healing, the story of an itinerant faith healer, a woman named Harlan who is one step ahead of hard times and of her own past. In a 1991 book of critical essays, called Liberating Voices, Jones had described the trajectory of Black literature as moving from “the restrictive forms (inheritors of self-doubt, self-repudiation, and the minstrel tradition) to the liberation of voice and freer personalities in more intricate texts,” and The Healing puts the author herself on that path. The narrative voice is that of a world-weary, often wry country preacher with a self-proclaimed ability to cure the sick and soul-wounded. As Harlan encounters believers and nonbelievers during her travels, Jones plants notions about how narratives are deployed in everyday life to both reveal and hide. The story’s small “tank towns” and ordinary people are familiar from her other books, but where the earlier work seems to resign itself to the world, The Healing holds forth the possibility of redemption.

The speed with which Jones presented the manuscript to Beacon suggests that it was a novel she had written earlier, and only then decided to publish. When it was named as a finalist for a 1998 National Book Award, Jones asked Michael Harper to attend in her place, eschewing industry hobnobbing for a private life in Kentucky.

This privacy was soon upended, after the Lexington police saw a celebratory article about her in Newsweek and, armed with the old warrant from Michigan, went to arrest Higgins, then living under the alias Bob Jones. When they arrived at the couple’s door, he threatened suicide rather than surrender. The police then called for a SWAT team. Higgins signaled his seriousness by taking up a kitchen knife. They stormed inside anyway, tackling Jones as Higgins did what he said he’d do. A district attorney defended the police’s “perfectly” executed handling of the warrant, noting that Higgins had written threatening letters about the shoddy hospital care his mother-in-law received, and that by the time the authorities arrived they were “sitting on a bomb.”

After her husband’s death, Jones was committed to a hospital amid fears that she might harm herself. When her fourth novel, Mosquito, appeared the following year, everyone flocked to it for clues about the tragedy. Instead, they were greeted with a wildly ambitious novel that took its inspiration from the free-form riffs of jazz, in line with Black writers like Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray. Jazz is many things, and Mosquito came from its more daring vein. It was not well received. In a pan of the book published in The New York Times, Henry Louis Gates Jr. complained that it

often reads more like Jones’s “Theory of the Novel,” her encyclopedic version of Jamesian prefaces, than like any of Jones’s previous works. It’s a late-night riff by the Signifying Monkey, drunk with words and out of control, regurgitating half-digested ideas taken from USA Today, digressing on every possible subject, from the color of the Egyptians to the xenophobia of the Great Books movement, from the art of “signifying” and the role of Africans in the slave trade to the subtleties of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

Clearly Gates likes to play the dozens.

The book demands to be taken more seriously. On the simple level of story, it’s about a truck driver named Mosquito—the only female on a route that traces the Mexican border—who becomes a coyote for a group called the Sanctuary, ferrying refugees on the “new Underground Railroad.” All of Jones’s women are on the run, but from book to book they become more likely to have a place to go. Mosquito is one of Jones’s trademark mash-ups—fusing her interests in history, character, and contemporary events. Time is collapsed, such that the past, present, and future play on a Finnegan’s Wake–style loop of language and consciousness. It’s an Olympian move, but if you’re Simone Biles, who’s to tell you not to play hopscotch with the gods? Like other late-postmodern works, the book overflows the usual frames of realism; it includes the author’s original theories about the relationship between story and life, between the speaker/writer and the listener/reader. It often sounds like overhearing a lunch date between Derrida and Calvino, at a table where both theorist and master are Jones. Mosquito didn’t find a general readership, but it helped feed a lot of dissertations.

Its reception aside, the novel marked a formal shift for Jones. The wealth of knowledge inside the author’s mind by then—the ideas, and the layers of experience she was trying to put across—strain the naive first-person narrator. Jones may have been listening to jazz, but she was also exploring the boundaries of what is possible in the modernist forms of the novel.

At 50, an age when many writers are just arriving at the height of their power, Jones might have been expected to tally the lessons from her experiment and keep moving. Indeed, Atwan said that Mosquito wasn’t yet published when Jones sent her the manuscript for Palmares. But for reasons unavailable to us, Jones—who communicated only sporadically with her Beacon editor—decided against following through with the book. And soon, Atwan said, Jones told her that she’d stopped writing entirely.

A main definition of a canonical artist is one whom other artists keep alive across generations. And word of mouth is what led me to Jones’s work a few years after college, when I decided to truly educate myself. As an aspiring novelist, I wanted to see where my own writing fit in, sure, but I’d also matured enough to realize that what I liked and didn’t like was irrelevant to the task of understanding the vastness of literature. During this years-long period, I read through the books that get anthologized as the American canon, the English, the World Lit, and sampled various national traditions. I read the Nobel Prize winners I hadn’t before. Harold Bloom was the GOAT among readers, so I measured myself in those days against the indexes of The Western Canon. You can read all of these things and still not know much about Black literature. My education there was in bookshops and libraries, but especially in talking with other writers, visual artists, musicians, filmmakers, dancers. It was the best education I ever had.

One Friday after work at my day job as a magazine writer, I made my way from Sixth Avenue to a bar in Hell’s Kitchen where industry people gathered. I joined some friends from Newsweek at the Black table, where they were sitting in stunned silence and self-reproach. Higgins had just killed himself, after the magazine outed his location. I don’t remember the specifics, but we talked bitterly about the editorial decisions that led the police to his door. About the things that white Americans understood and did not understand about being Black in this country. Things they might not wish to know.

The reason I’ve told you all this is so you’ll understand what I mean when I say that Gayl Jones’s new work is as relevant as ever. With monumental sweep, it blends psychological acuity and linguistic invention in a way that only a handful of writers in the transatlantic tradition have matched. She has boldly set out to convey racial struggle in its deep-seated and disorienting complexity—Jones sees the whole where most only see pieces.

More than a third of all Africans removed from their homeland from the early 1500s to the mid-1800s—more than 4 million people—were transported to Brazil and enslaved alongside the indigenous people, at least those who hadn’t been exterminated. Today Nigeria is the only country with a larger Black population than Brazil, and in the body of African American culture stretching from Harlem to Rio, the state of Bahia might be fairly viewed as its spiritual heart. Perhaps the heart of the entire Black world. Palmares centers on the reenslavement of the last settlement of free Blacks in Brazil—and is told from the point of view of Almeyda, a young girl who has learned to read with the help of a local Catholic priest named Father Tollinare, though he tries to limit the books available to her. The novel has a García Márquezean pace, and, because it imitates the rhythms of Portuguese and imports words without the usual linguistic signposts, it almost feels as though it has been translated into English. But where García Márquez writes of generals and doctors, Jones tells of slaves and whores. The rhetoric of race in Latin America is different from our own, of course, but its history, and the ways blood and money operate, are familiar.

Plot is beside the point in Palmares—the book unfolds on a plane of consciousness where the things achieved are shifting relationships and states of being. Ultimately, the book is about taking full possession of the entire Black experience, including tenderness—and Jones’s quest to free the individual Black voice. Father Tollinare, born back in the Old World and wedded to its old sounds, doesn’t realize his young student’s hunger to expand and integrate:

During the studies, he’d pass one worn Bible around and we’d read the stories, and he’d shake his head when we dropped letters off the ends of words, and he’d say, “In Portugal they say it this way.” “But here we say it this way,” I protested once. He looked at me sternly … I was silent because I wanted to know how to read and write the words, even if I continued to pronounce them a different way.

At her best, Jones wields the words of a larger literary tradition with a subversive power that is rare in its all-encompassing purity. Dropping letters, she adds new worlds to that tradition, one that has been—in this country, and in the American language—as versed in duplicity as in revelation. One wishes that the blooming of Jones’s genius were as simple as the saying “You can’t keep a good woman down.” The truth is, you can, and it’s been done for centuries. The old women in Kentucky presumably told her that long ago, and how best to endure.

* Beacon Press previously told The Atlantic that it would be publishing Palmares in September 2020. After this article went to press, the publisher confirmed that the book will in fact be released in September 2021. The article has been updated online to reflect this. It appears in the September 2020 print edition with the headline “‘No Novel About Any Black Woman Could Ever Be the Same After This.’”